The New Testament gives two different accounts of what happened when Paul and Silas preached the gospel in Thessalonica. One tells the external events, but the other gives the spiritual and theological meaning.

The New Testament gives two different accounts of what happened when Paul and Silas preached the gospel in Thessalonica. One tells the external events, but the other gives the spiritual and theological meaning.

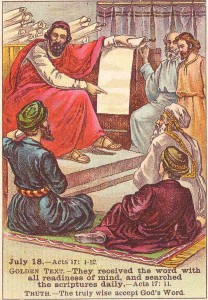

Acts 17 has a fairly brief report (sandwiched in between the longer reports on the work in Philippi and Athens): Paul went the synagogue and

on three Sabbath days he reasoned with them from the Scriptures, explaining and proving that it was necessary for the Christ to suffer and to rise from the dead, and saying, “This Jesus, whom I proclaim to you, is the Christ.” And some of them were persuaded and joined Paul and Silas, as did a great many of the devout Greeks and not a few of the leading women.

That tells us a lot in a few words: Where Paul and Silas based their ministry (the synagogue), how Paul argued (from the Scriptures), what he said (Jesus is the Messiah who died and rose in fulfillment of prophecy), and who responded (“some” of the Jews, “a great many” of the Greeks, and “not a few” of the women).

But then Luke fastens on one aspect of the Thessalonian ministry that dominates his presentation: the way some of the members of the synagogue became highly effective anti-Paul agitators. They recruited some rabble, got a mob going, and picked someone to attack (“Jason! Get him!”). All things considered, the believers in town decided it was best for Paul and Silas to slip away by night. Off they went to Berea, and Luke significantly observes that the Berean Jews were “more noble than those in Thessalonica.” These Jews “received the word with all eagerness, examining the Scriptures daily to see if these things were so,” and as a result they became believers, as did many Greeks and (again!) several important women. But those agitators from Thessalonica showed up in Berea and started the trouble all over again, so Paul went off (alone) to Athens to try preaching to the Greeks. For Luke, in the flow of Acts, the story of the Thessalonian mission includes a brief report of successful work, but seems dominated by the opposition and rejection.

From Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians, though, we can reconstruct a positive account of what the gospel does when it is received by a community. Paul seems struck by the fact that the Thessalonians who accepted his message did not just take his words as human words, but received his message as God’s word:

And we also thank God constantly for this, when you received the word of God, which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men but as what it really is, the word of God, which is at work in you believers.

The fact that they received the gospel (“This Jesus, whom I proclaim to you, is the Christ”) as God’s own word demonstrates to Paul that they are “brothers, loved by God,” and that God has chosen them. The gospel that Paul preached came “not only in word,” but also (1 Thess 1:5) in these three things:

1. in power

2. and in the Holy Spirit

3. and with full conviction (plerophoria)

so that they became imitators of the apostles and Jesus, receiving the word

1. in much tribulation

2. with the joy of the Holy Spirit.

And that’s what happened in Thessalonica.