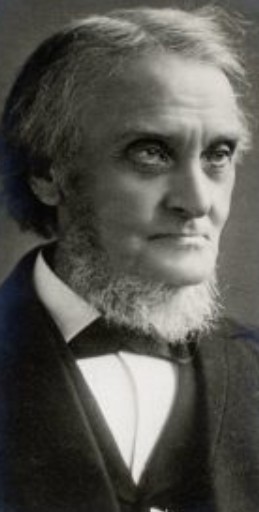

Chief among the many gifts of Alexander Maclaren (1826-1910) was his ability to explain, expound, expand, embiggen, and so on, any passage of Scripture he turned his attention to. It is really remarkable how much this nineteenth-century Baptist preacher could find in a single, short passage. To see him making full use of his considerable resources, you should probably read through a long section of his continuous work on the Gospels or on Colossians, but what recently caught my eye was his ability to open up one brief passage from Isaiah 12:3: “With joy shall ye draw water out of the wells of salvation.”

Chief among the many gifts of Alexander Maclaren (1826-1910) was his ability to explain, expound, expand, embiggen, and so on, any passage of Scripture he turned his attention to. It is really remarkable how much this nineteenth-century Baptist preacher could find in a single, short passage. To see him making full use of his considerable resources, you should probably read through a long section of his continuous work on the Gospels or on Colossians, but what recently caught my eye was his ability to open up one brief passage from Isaiah 12:3: “With joy shall ye draw water out of the wells of salvation.”

The wells of salvation, says Maclaren, are certainly not cisterns or water-jugs; they are not the containers but the sources of the water:

The idea of the word here is not that which we attach to a well, but that which we attach to a spring. It does not describe the source of salvation as being a mere reservoir, still less as being a created or manufactured thing; but there lies in it the deep idea of a source from which the water wells up by its own inward energy. Then, when we have got that explanation, and the deep, full, pregnant meaning of the word salvation as a thing past, a thing present, a thing future, a thing which negatively delivers a man from all sin and sorrow, and a thing which positively endows a man with beauty, happiness, and holiness-when we have got that, then the question next cries aloud for answer –this well-spring of salvation, is –what? Who? And the first answer and the last answer is GOD –GOD HIMSELF.

Describing the source of salvation with the poetic image of a well-spring, then, communicates something crucial about the biblical character of salvation:

It is no mere bit of drapery of the prophet’s imagery, this well-spring of salvation; it is something much more substantial, much deeper than that. You remember the old psalm, ‘With Thee is the fountain of life: in Thy light shall we see light’; and what David and John after him called life, Isaiah and Paul after him calls salvation. And you remember too, no doubt, the indictment of another of the prophets, laying hold of the same metaphor in order to point to the folly and the suicide of all godless living: ‘My people have committed two evils: they have forsaken Me, the fountain of living waters, and they have hewn out for themselves broken cisterns.’ They were manufactured articles, and because they were made they could be cracked, but the fountain, because it rises by its own inherent energy, springing up into everlasting life, is all-sufficient. God Himself is the well-spring of salvation.

“If I had time to enlarge on this idea,” says Maclaren –ah, but that’s all Maclaren ever does, is take time to enlarge on an idea. He builds up so much from this single phrase that he makes you feel utterly embarrassed that you ever rushed over the words “wells of salvation.” In fact, this phrase — “with joy draw water out of the well”– is an apt description of Maclaren’s expository and theological method.

If I had time to enlarge upon this idea, I might remind you how nobly and blessedly that principle is confirmed when we think of this great salvation, past, present, and future, negative and positive, all-sufficient and complete, as having its origin in His deep nature, as having its process in His own finished work, and as being in its essence the communication of Himself. That last thing I should like to say a word or two about. If there is a man or a woman that thinks of salvation as if it were merely a shutting up of some material hell, or the dodging round a corner so as to escape some external consequence of transgression, let him and her hear this: the possession of God is salvation, that and nothing else. To have Him within me, that is to be saved; to have His life in His dear Son made the foundation of my life, to have my whole being penetrated and filled with God, that is the essence of the salvation that is in Jesus Christ. And because it comes unmotived, uncaused, self-originated, springing up from the depths of His own heart; because it is all effected by His own mighty work who has trodden the winepress alone, and, single-handed, has wrought the salvation of the race; and because its essence and heart is the communication of God Himself, and the bestowing upon us the participation in a divine nature, therefore the depth of the thought, God Himself is the well-fountain of salvation.

The intensity of this personalism penetrates pretty deeply into the biblical view of salvation, but it would remain a bit abstract without further specification. Maclaren provides this specification, in two ways. First, he applies the passage to Jesus, or rather, shows that Jesus applied it to himself when he “stood up the last day of the feast and said, ‘If any one thirsts, let him come to me.”

Let me ask you to go with me one step further, and to figure to yourselves the significance and the strangeness of that moment to which I have already referred, when a man stood up in the temple court, and, with distinct allusion to the whole of the multitude of Old Testament sayings, in which God and the communication of God’s own energy were represented as being the fountain of salvation and the salvation from the fountain, and said, ‘If any man thirst, let him come unto Me.’

Why, what a thing –let us put it into plain, vulgar English-what a thing for a man to say– ’If any man thirst.’ Who art Thou that dost thus plant Thyself opposite the race, sure that Thou hast no needs like them, but, contrariwise, canst refresh and satiate the thirsty lips of them all? Who art Thou that dost proclaim Thyself as sufficient for the fruition of the mind that yearns for truth and thirsts for certitude, of the parched heart that wearies and cracks for want of love, of the will that longs to be rightly and lovingly commanded? Oh, dear brethren, not only the Titanic presumption of proposing oneself as enough for a single soul, but the inconceivable madness of proposing oneself as enough for all the race in all generations to the end of time, except on one hypothesis, marks this utterance of Him who has also said, ‘I am meek and lowly of heart.’ Strange lowliness! singular meekness! Who was He? Who is this that steps into the place that only a God can fill, and says, ‘I can do it all. If any man thirst, let him come unto Me and drink’?

Dear brethren, some of us can, thank God, answer that question as I pray that every one of you may be able to answer it, ‘Thou art the King of Glory, O Christ; Thou art the everlasting son of the Father. With Thee is the fountain of life; Thou Thyself art the living water.’

And secondly, Maclaren specifies the nature of salvation by pointing us not simply to Jesus as the Son of God, but to the specific work of salvation he carried out in his death and resurrection:

The words which precede my text are a quotation from a song of the Israelites in their former Exodus: ‘The Lord Jehovah is my strength and my song; He also is become my salvation.’ Now, if our Bible has been correct-and I do not enter upon that question-in emphasising the difference between is and is become, mark where it takes us. It takes us to this, that there was some single, definite, historical act wherein God became in an eminent manner and in reality what He had always been in purpose, intent, and idea. Then that to which my text originally alludes, to which it looks back, is the great deliverance wrought by the banks of the Red Sea. It was because Pharaoh and his hosts were drowned in it that Miriam and her musical sisters, with their timbrel and dance, not only said, ‘The Lord is my strength,’ but ‘He has become my strength’-there where the corpses are floating yet. What answers to that in the matter with which we are concerned? Brethren, it is not enough to say that God is the fountain of salvation, it is not enough to say that the Incarnate Christ is the medium of salvation. Will you take the other step with us, and say that the Cross of Christ is the realisation of the divine intention of salvation? Then He, who from everlasting was the strength and song of all the strong and the songful, is become the salvation of all the lost, and the fountain is ‘opened for sin and for uncleanness.’ A definite, historical act, the manifestation of Jesus Christ, is the bringing to man of the salvation of God. So much, then, for that first point to which I desired to ask your attention.

Looking at the same passage, John Gill notes that “springs” is plural, and argues by cross-references that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are each sources of salvation. But Maclaren’s emphasis is on the one salvation, so he mutes the plural. No doubt he could have gone even further in expanding the meaning of these well-springs; he also has much to say about what it means to draw out this water (it’s all about proper use of the ordinances) and why it is joy that characterizes both the process and the result.