In theological anthropology, some of the best witnesses to the nature of true humanity are those traditions which were forced to refute, in doctrine and in practice, the motivated denial of their own humanity. When African-American Christians, for example, found their footing and secured the kind of academic tools they needed to carry out a sustained theological argument at a high level, they used arguments which it would not have occurred to anybody else to use. They valued some truths more deeply, and shrugged off some conventions so completely, that they came at the common work of theological anthropology from a different angle. Their situation evoked creative solutions that not only addressed their own needs, but which are a permanent witness to the task of Christian reflection on the nature of humanity.

Recently I discovered a fascinating, untapped resource in the work of Benjamin Tucker Tanner, a nineteenth-century African-American theologian whose practical concerns about the Christian doctrine of humanity motivated a wide-ranging scholarly project in the (to me, surprising) fields of ethnology and world chronology, and also positioned him to offer a two-volume account of the coherence of salvation history.

Here’s the story. Several years ago I was prepping to teach a class on the Gospel of Matthew for the Los Angeles Bible Training School, and was looking for some visuals to use as background material. I love Rembrandt’s drawings of the life of Jesus, and I figured I would just use them. But I could only find a few of the scenes I needed, and I didn’t want to fill in gaps with other painters; I was really committed to sticking with the work of one artist, to give the whole semester a single visual theme.

Here’s the story. Several years ago I was prepping to teach a class on the Gospel of Matthew for the Los Angeles Bible Training School, and was looking for some visuals to use as background material. I love Rembrandt’s drawings of the life of Jesus, and I figured I would just use them. But I could only find a few of the scenes I needed, and I didn’t want to fill in gaps with other painters; I was really committed to sticking with the work of one artist, to give the whole semester a single visual theme.

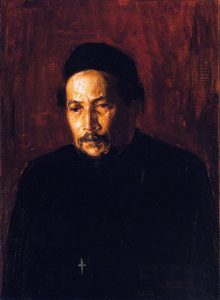

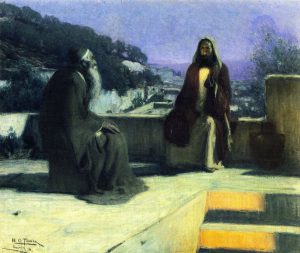

After a little searching, I found the biblical paintings of Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), which worked perfectly and have been a constant companion for me ever since. Tanner brought the extra benefit of being an African-American painter –the first famous African-American painter, in fact– and I liked this fact especially because LABTS is a historically black Bible school that now serves a very diverse population. Tanner’s paintings function very well as visual support for Bible teaching. They’re powerful but quiet, rich but chromatically disciplined, suffused with spirituality, and informed by close observation of middle eastern culture (and light!). So it was good to be able to introduce these students to Tanner’s work, even just as visual enrichment to lectures. I wrote a little bit about his paintings and his religious outlook at this blog post.

Recently I got to lecture on Tanner’s paintings for friends at The Field School in Chicago. While pulling together some information about Tanner (whose reputation seems to be rising in the last decade, I’m glad to report), I began to be interested in his father, Benjamin Tucker Tanner. One of the great things about coming back to study a subject again is that you can look a little deeper into parts of it that you had to hurry past the first time.

It turns out, Benjamin Tucker Tanner was pretty amazing in his own right. So here are some notes about him, mainly as a placeholder for me so that next time I get to come back around and study him, I know where to start. By the way, if you’re a grad student looking for a project that is both valuable in itself and wide open for new research, here it is. Beat me to it and do it well and it’s all yours.

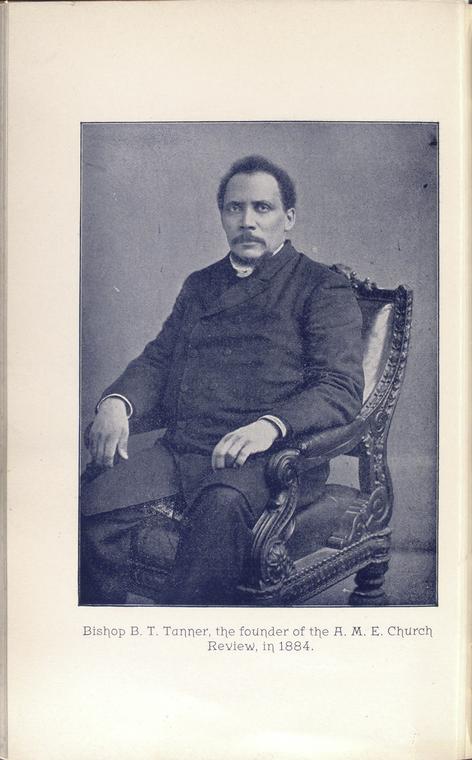

B. T. Tanner (1835-1923) was a bishop (only the eighteenth ever) in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (read my notes on the denomination’s founding here). The A.M.E. was founded by hard-working preachers and evangelists, and was not able to produce a scholarly class of leaders until… well, pretty much the time of B.T. Tanner. I think this is the key to understanding Tanner’s contribution: he devoted his life to giving the A.M.E. church the academic representation it deserved. Tanner was born free (his wife, though, was born in slavery) in Pennsylvania, and had access to education from the beginning: he attended Avery College and Western Theological Seminary. By the time of the Civil War he set up a school for recent freedmen, connected with the Navy. And he wrote, with careful concern for scholarly integrity and accountability, but also with a steady vision of serving African American Christians with relevant educational material.

Tanner is above all a theologian and Bible teacher, which may partly explain the eclipse of attention to his work in the last century. He is directly engaged with social and political concerns of his turbulent times, but mostly what he wants to talk about is the God of the Bible. He also doesn’t perfectly fit the scripts we’re told to expect from the main lines of American intellectual history: he was friends with Booker T. Washington, and lectured at Tuskegee; but he was also one of the eighteen members present, with W.E.B. DuBois, at the founding of the American Negro Academy on March 5, 1897. That person is not supposed to exist, but his name was Benjamin Tucker Tanner. His eclectic ideas about issues like integration, competition, economic empowerment, and separatism also fail to sort into the clear patterns we now expect to have been available to nineteenth-century black thinkers.

The lion’s share of his early work was editorial: he took over editorial leadership of The Christian Recorder, a negro newspaper, from 1864 to 1884, at which point he founded in 1884 The African Methodist Episcopal Review. His editorials and activity are all over those important historical journals. One of the issues that comes up repeatedly is the question of the most appropriate and helpful ethnic terminology. Tanner has definite opinions on this, always keeping etymologies in mind (Africa is a place; negro is a color, etc.), and is part of the lively contemporary conversation. He weighed in on plenty of current events, usually with an intentionally Christian approach.

The lion’s share of his early work was editorial: he took over editorial leadership of The Christian Recorder, a negro newspaper, from 1864 to 1884, at which point he founded in 1884 The African Methodist Episcopal Review. His editorials and activity are all over those important historical journals. One of the issues that comes up repeatedly is the question of the most appropriate and helpful ethnic terminology. Tanner has definite opinions on this, always keeping etymologies in mind (Africa is a place; negro is a color, etc.), and is part of the lively contemporary conversation. He weighed in on plenty of current events, usually with an intentionally Christian approach.

But Tanner also published the following books:

Apology for African Methodism (1867). An apology (“in the ecclesiastical sense”) for Methodism itself (“Methodism has been well defined a Christianity in earnest.”) but especially for the A.M.E. denomination. Tanner is already a churchman in this early book, with a wide ecumenical vision. He is eager to show that his church is part of the great Christian tradition, and not schismatic. The reason it is a distinct body from others has to do with the racism and prejudice that required its founders to strike out on their own: Richard Allen did not bring any new doctrine whatsoever, but “felt that the humane teachings of Scripture had been disregarded, that partiality the most flagrant had been entertained and practiced against him and his race.”

Origin of the Negro, and Is the Negro Cursed? (1869). Here Tanner directly confronts racist biblical scholarship of the kind that argued that negroes were under a curse since Genesis, and doomed to enslavement. To counter this scholarship, Tanner embraced both biblical and classical historical ethnology. For him, it was crucial to mark the fact that the Genesis curse falls on Canaan, not Ham; Ham he traces to Africa (Cush, Ethiopia), Mizraim to Egypt, and so on. In Tanner’s brief argument, racist scholarship had bad motives for tracing the curse to Ham, but “the impossibility of locating Canaan in Africa, in no little measure accounts for the strenuous determination which the same slaveocrats have ever made to fix the crime on Ham.” Tanner will return to this field of argument repeatedly over the years. He is battling secular ethnology on the one hand by championing the truthfulness and importance of the biblical witness to ancient people groups, and pro-slavery biblicists on the other hand. It’s this pro-Bible, counter-racist agenda, carried out at the level of public intellectual argumentation, that makes Tanner so unique, especially as he performs the argument “as a negro, for the negro.”

Outlines of History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (1882). Written largely in catechetical Q&A form, but also including historical documents, this book serves the denomination’s educational needs directly. Begins with a touching hymn, by Tanner (he wrote several), on preserving the church of the fathers and mothers.

Theological Lectures (1894). Maybe the best place to get a grip on Tanner’s mind. These are lectures he gave during a teaching visit to Tuskegee (you sometimes see the book listed as “Tuskegee Lectures” or “Biblical Lectures,” but the TOC at least is identical). Here he is bringing his learning into service of the common man, for a broad educational mission. Twelve lectures; three each on Biblical Chronology; Symbolism; Harmony of the Gospels; and Life and Ministry of Jesus. The preface, by Bishop James Handy, points out that in these lectures, “biblical poetry and symbolism receive what is possibly the most extended treatment by the hands of any man of the Afro-American race.” And he also notes that

A feature of the lectures, worthy of exceptional notice, is the Race feature. The Bishop’s views of the great facts which come under notice, are the views of a member of the Hamitic branch of the common race; and upon more than one occasion, attention is called to the fact that Japheth has painted everything to suit himself, and often to the detriment of that which is fair and honest.

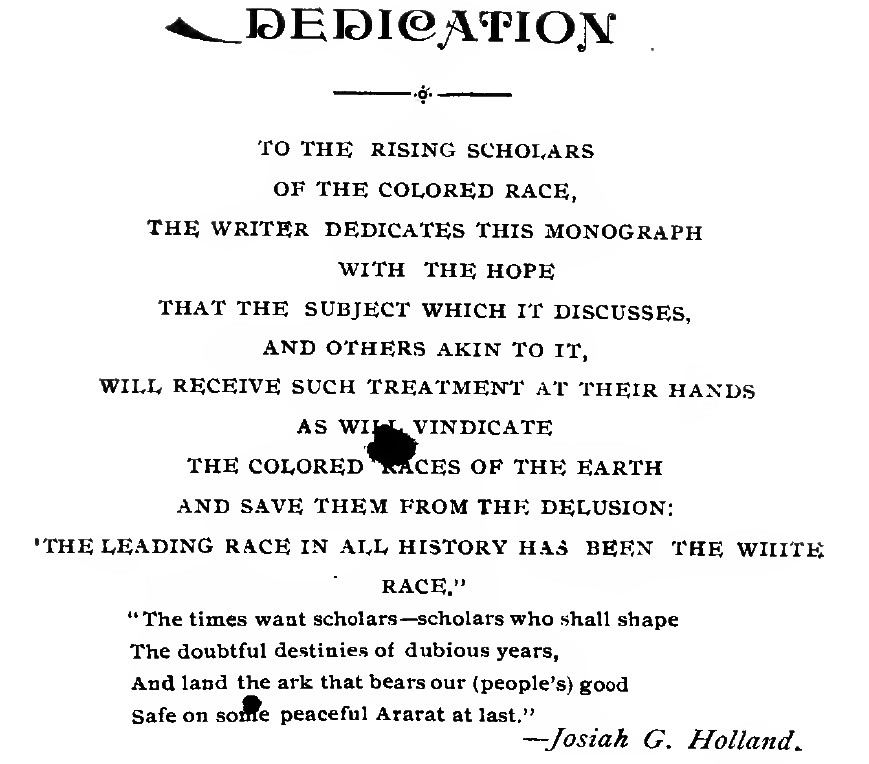

The Color of Solomon: What? (1896) More counter-racist scholarship; in some ways Tanner’s most readable contribution because it has a somewhat lighter touch. Tanner admits that the subject of Solomon’s skin color is, in itself, trivial. But “In times like tehse when we read constantly of the ‘White City,’ the ‘White Squadron,’ the ‘White Race,’ etc.,” it is worth pointing out that the translation “my beloved is white and ruddy” is not right. Throughout his counter-racist work in historical ethnography, Tanner argues that a yellowish dark skin color is the norm for humans and is what we should picture when picturing most Bible stories; very light skin in the north (“white”) and very dark skin in the south (“black,” “negro”) are extremes of human pigment possibility. This book has the following dedication:

(The delusion he quotes is directly from an 1890 book by Brinton, a Phildelphia professor of ethnology.)

The Negro in Holy Writ (1898). Less than a hundred pages, and correlating Herodotus with Scripture, this short book establishes that the Negro race is described in the Bible, contra recent attempts to read them out of it. Notice again Tanner working against the constraints of a double bind: either black people are in the Bible and it proves they should be slaves, or they’re not in the Bible because they are not a people. Guy can’t catch a break. Secularist canon to the left of him, slaveocrat canon to the right of him, into the valley of oppressive scholarship rode Benjamin Tucker Tanner.

The Dispensations in the History of the Church and the Interregnums, 2 vols, 1899. This amounts to 700 pages of work produced by a mature scholar. I can’t wait to spend some time with it, but I haven’t yet. It’s a little bit genre-defying (biblical theology? apologetics?), and it proceeds sometimes by way of Very Large Quotations. But it really looms as one of those books you can’t believe you’ve never heard of before. Tanner is a Methodist (infant baptist, Wesleyan soteriology) trained at Western Theological Seminary and quick with a quotation from Owen or other Reformed standards; some elements that seem like nascent dispensationalism are evident here, but the covenant framework is pronounced and he’s not drawing charts (won’t even commit to a definite number of dispensations). Tanner is a lively writer, even when he has to descend to minutiae, so this should be in one sense an easy read. There’s a modern biography of Tanner in historical mode, but nobody has taken him seriously as a theologian who produced a serious systematic overview of salvation history. Let’s do it.

The dedication:

A couple of interesting passages about how Tanner read the need of the hour, and his own vocation:

In so far as we Afro-Americans are concerned the demand of the hour is Negro scholarship; especially on the line of Biblical ethnology. Why not say ethnology in general? No; our want is for the knowledge of the ethnology of the Bible, and for the reason that by no other book does the white man swear… (I:12)

A chief reason is the attempt now being made by Japhetic scholarship to deny our Hamitic genesis…Our duty is to rally around the statements of the Bible, particularly those of Genesis, tenth chapter. Make it the citadel of our contention for a share in the common heritage. (I:13)

Our scholars then –the few that are, the host that will be– must listen to Longfellow: Let us then be up and doing, With a heart for any fate. (I:14)

The Descent of the Negro (1898). This booklet is an excerpted chapter from Tanner’s Dispensations, released in advance, and designed to be widely available as a corrective to the influence of some flawed Sunday School literature. A note from the publisher’s preface:

Tanner’s first book, of which I can only find the title, was Paul versus Pius Ninth. The title suggests Protestant polemics, but as I say, I haven’t seen a copy yet.

I see one book about Tanner, Fire in his Heart by William Seraile, which I haven’t looked at yet.