I recently learned that the Bible Institute of Los Angeles, through its monthly magazine The King’s Business, took a stand against racial segregation in 1957. This 1957 broadcasting of Biola’s institutional position was neither so early as to be cutting-edge, nor so late as to be irrelevant. Here’s the story.

I recently learned that the Bible Institute of Los Angeles, through its monthly magazine The King’s Business, took a stand against racial segregation in 1957. This 1957 broadcasting of Biola’s institutional position was neither so early as to be cutting-edge, nor so late as to be irrelevant. Here’s the story.

Biola’s magazine stated its view publicly in two ways, both of them in the November 1957 issue. First, managing editor Lloyd Hamill wrote an editorial, “The Problem of Segregation and the Christian,” which was provoked directly by current events. Hamill was defending President Eisenhower’s decision to send federal troops into Little Rock to overcome resistance to the integration of schools. “There were dark comments of dictatorship and storm troopers” to be heard when Eisenhower took this action. But, Hamill argued, “actually had the President failed to act when he did he would have been misusing his high office. What he did was both legally and morally correct.”

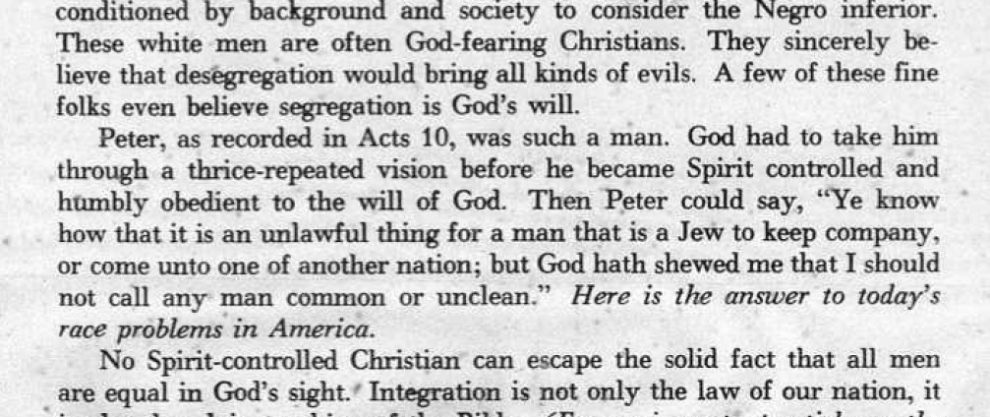

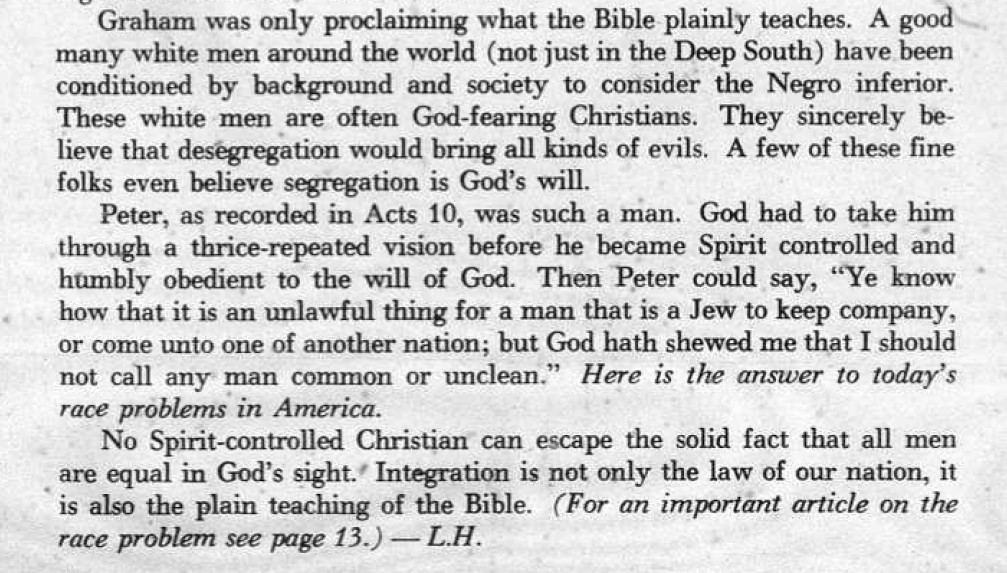

That brief editorial went on to sketch a biblical argument (signalling Acts 10 in particular) for a mandate to integrate the races. Hamill acknowledged that white people who had been historically and socially conditioned “to consider the Negro inferior” were often sincere in their views: “These white men are often God-fearing Christians. They sincerely believe that desegregation would bring all kinds of evils. A few of these fine folks even believe segregation is God’s will.” But these people need to become “Spirit controlled and humbly obedient to the will of God,” accepting integration like Peter accepted the Gentiles in Acts 10. And “no Spirit-controlled Christian can escape the solid fact that all men are equal in God’s sight. Integration is not only the law of our nation, it is also the plain teaching of the Bible.”

That brief editorial went on to sketch a biblical argument (signalling Acts 10 in particular) for a mandate to integrate the races. Hamill acknowledged that white people who had been historically and socially conditioned “to consider the Negro inferior” were often sincere in their views: “These white men are often God-fearing Christians. They sincerely believe that desegregation would bring all kinds of evils. A few of these fine folks even believe segregation is God’s will.” But these people need to become “Spirit controlled and humbly obedient to the will of God,” accepting integration like Peter accepted the Gentiles in Acts 10. And “no Spirit-controlled Christian can escape the solid fact that all men are equal in God’s sight. Integration is not only the law of our nation, it is also the plain teaching of the Bible.”

The second step Biola took in this issue of The King’s Business was to publish a longer article on the subject: “Segregation: Spiritual Frontier,” by Robert James St. Clair, listed as “minister of North Fairmount Presbyterian Church, Cincinnati.” St. Clair would later work in Berkeley, CA, serving on the staff of First Presbyterian Church and teaching as an adjunct at the Pacific School of Religion.

His King’s Business article is a little bit rambling. You can flip through it at Biola’s digitized archive here, or I’m posting an ugly-scanned pdf of the whole piece here, because it’s so important to get a historical source’s actual tone of voice, warts and all: these voices are often most instructive when they are least like us (personally I find his attempt to flip the “savages” script pretty inept, but his ability to perceive northern bigotry against Puerto Ricans surprisingly insightful). St. Clair’s main point is that you can tell when somebody has begun thinking spiritually about race issues when they stop settling for merely natural categories and descriptions. St. Clair asks his readers to consider if they talk about “the integration of races in the churches” in terms that “recite popular theories,” appeal to American laws, and argue about the natural vigor of various races. If so, he says, they are speaking from “naturalistic viewpoints” rather than a spiritual one. To think biblically and spiritually about race is to cross the “spiritual frontier” of his title.

A few favorite quotations from St. Clair’s “Spiritual Frontier” article:

“The Church of Jesus was created to thrive on the spiritual frontiers of the world.”

“If you want to study the function of the Church, look first at Ephesians. Barriers existed between Jew and Gentile. The blood of Christ washed these barriers away.”

“Now and then you hear some Christian say, ‘I don’t want any Negroes or Mexicans in my church.’ In whose church? Christ paid for the Church with His precious blood and some saints seem to think because they put an offering in the plate on Sunday they have bought the Church back.”

“If the world sees that hatred and suspicion among races are practiced by churches too, then the Church will not be heard when it talks about anything else.”

“A holy Church is a Church of power but holiness does not consist of saying one thing and doing another.”

“It is true that conquering racial tensions by the love and power of Christ will not bring in the millennium. However, today that is one of many challenges to the Church. Tomorrow there will be others, and tomorrow and tomorrow, until He returns from on high.”

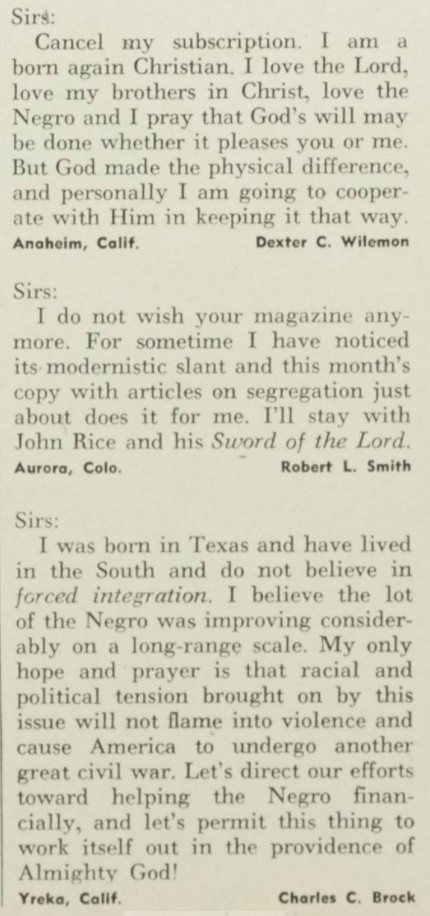

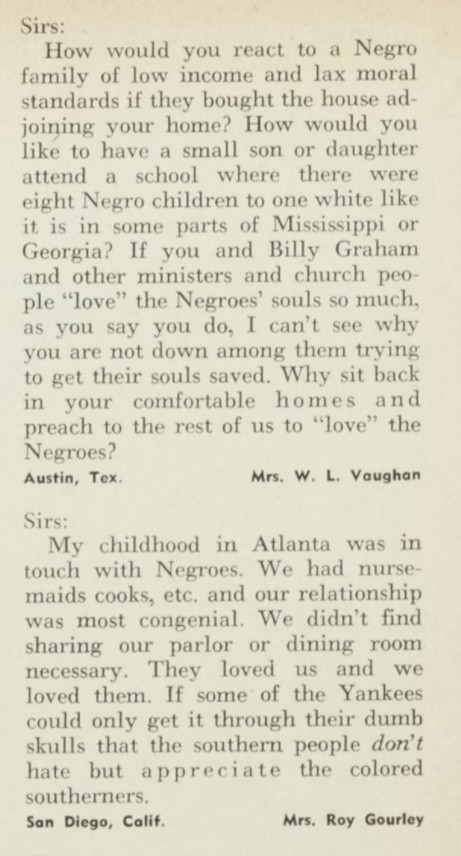

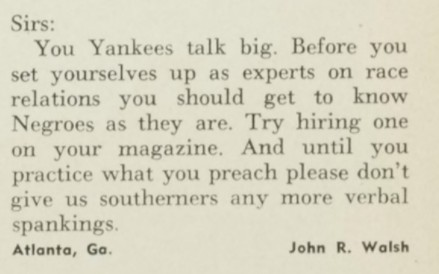

How was this 1957 issue of The King’s Business received by the magazine’s readers? In a 2013 study, “Neoevangelicalism and the Problem of Race in Postwar America” (in Christians and the Color Line: Race and Religion After Divided by Faith, ed J. Russell Hawkins and Phillip Luke Sinitiere (Oxford, 2013)), historian Miles Mullin studied that very question. He noted that King’s Business readers generally did not look to the magazine for political content, and that throughout the late 40s and early 50s its editorial stance showed ambivalence about controversial racial issues such as voluntary segregation and mandatory integration. That makes this 1957 editorial stand out. Mullin says

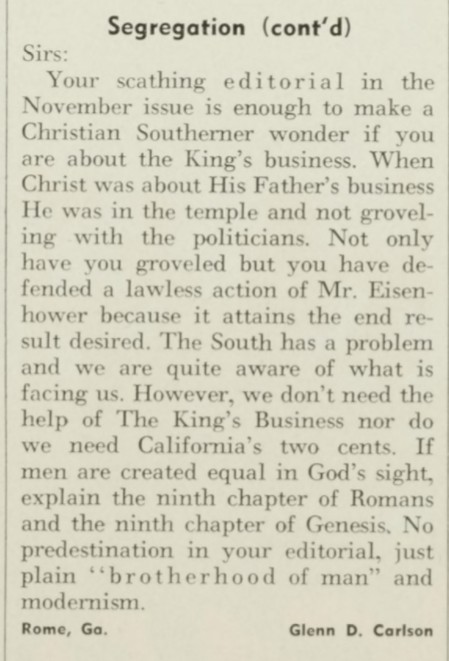

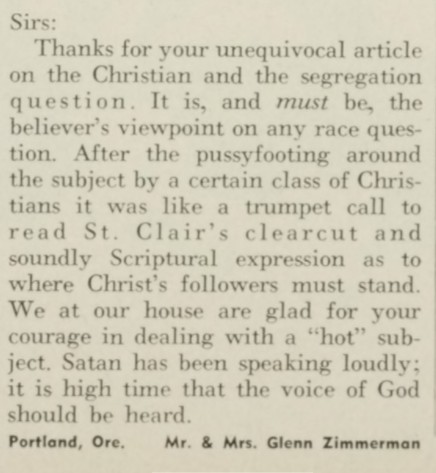

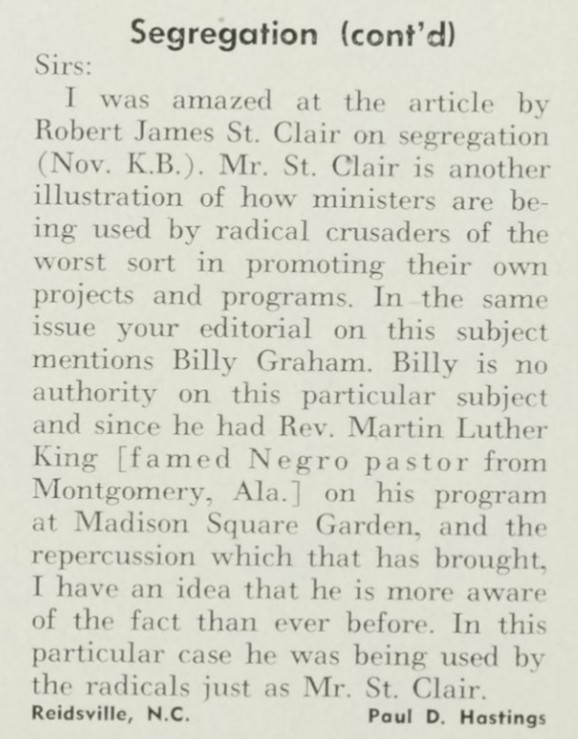

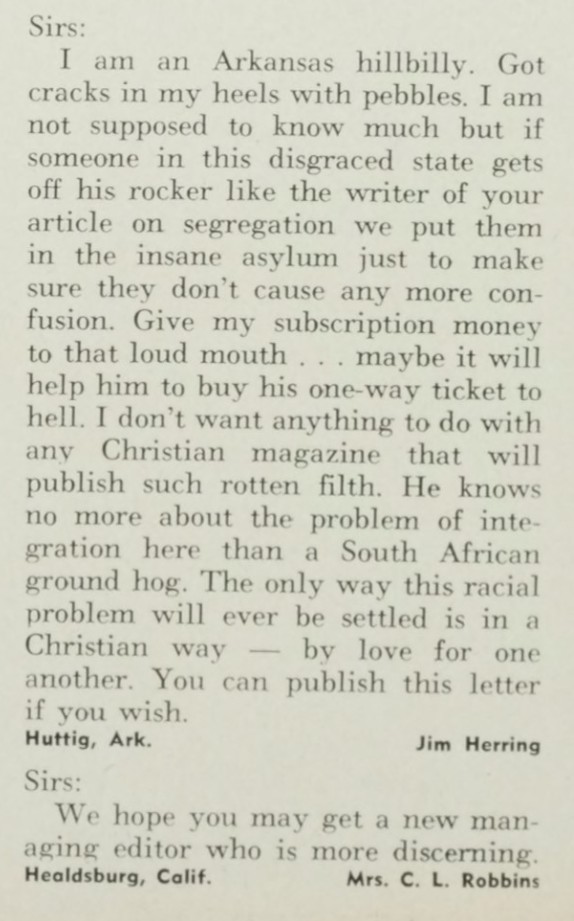

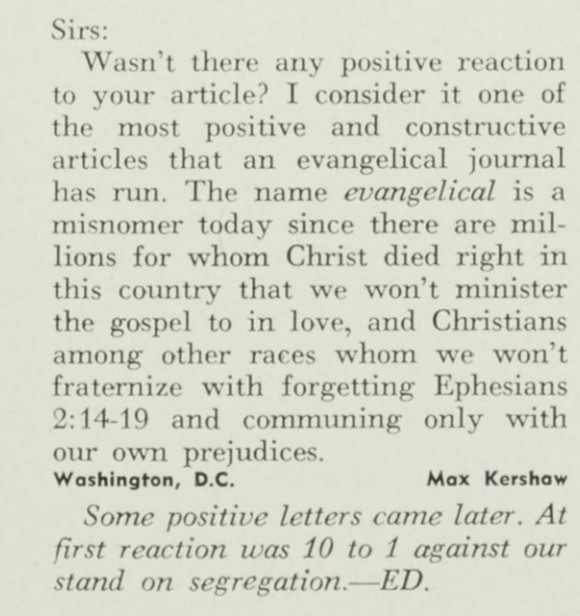

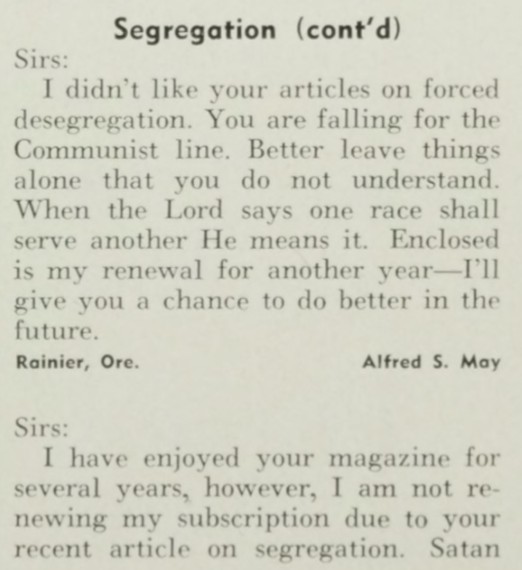

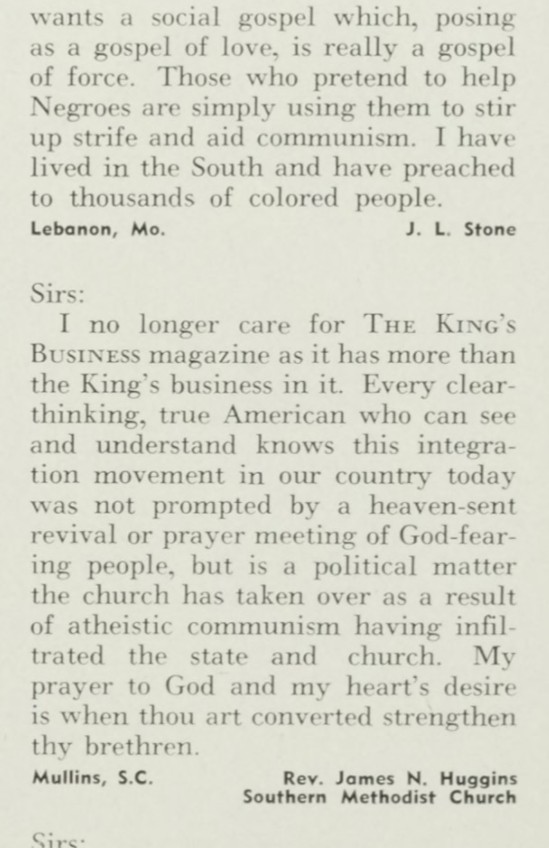

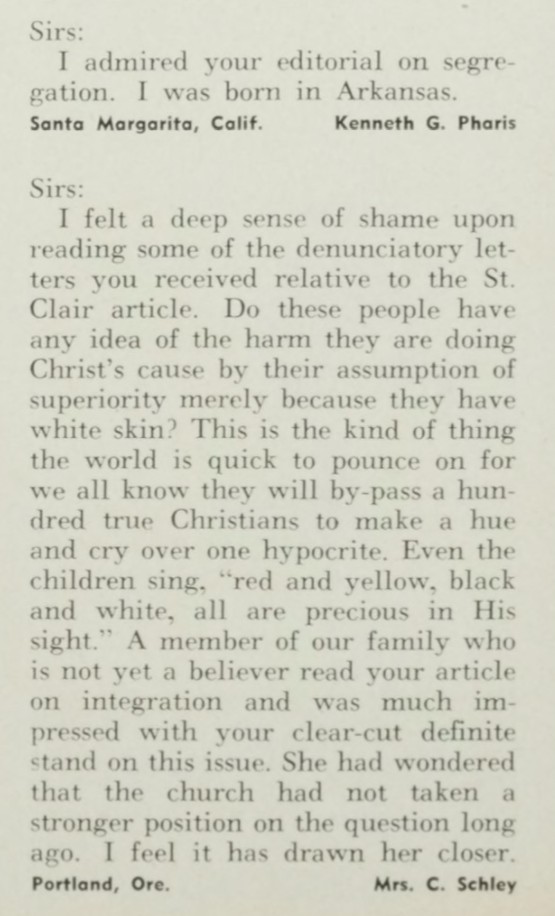

the editors of the magazine received a deluge of letters from writers who decried their stance, accusing them of falling victim to communist propaganda, abandoning the ‘King’s business’ for politics. Several asked for their subscriptions to be cancelled. Although the editors conceded that letters ran ten to one against their ‘stand on segregation’ in the early going, they did receive several commendatory letters and additional contributions for compensatory ‘gift subscriptions.’ (Mullin’s footnote points to the “Reader Reaction” feature in King’s Biz issues from the first four months of 1958.)

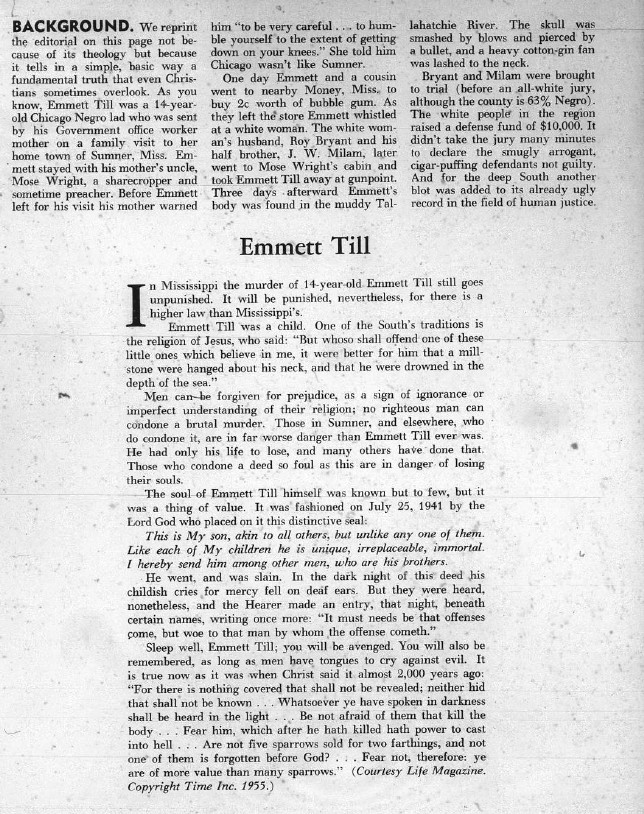

Mullin also helpfully connects the dots to an editorial that had run two years earlier in the King’s Business, also by managing editor Lloyd Hamill. That December 1955 editorial (pictured here) was a brief prefatory note and a reprinting of Life Magazine’s own fiery editorial about the murder of Emmett Till, and the southern white jury’s exoneration of his murderers. Hamill noted, “we reprint the editorial… not because of its theology but because it tells in a simple, basic way a fundamental truth that even Christians sometimes overlook,” adding only that “for the deep South another blot was added to its already ugly record in the field of human justice.”

Mullin also helpfully connects the dots to an editorial that had run two years earlier in the King’s Business, also by managing editor Lloyd Hamill. That December 1955 editorial (pictured here) was a brief prefatory note and a reprinting of Life Magazine’s own fiery editorial about the murder of Emmett Till, and the southern white jury’s exoneration of his murderers. Hamill noted, “we reprint the editorial… not because of its theology but because it tells in a simple, basic way a fundamental truth that even Christians sometimes overlook,” adding only that “for the deep South another blot was added to its already ugly record in the field of human justice.”

For even more archival detail and context, check out Adam Laats’ book Fundamentalist U: Keeping the Faith in American Higher Education. Laats even dives into Biola’s student newspaper The Chimes, and some behind-the-scenes stuff with President Sam Sutherland.

In civil rights history, it was a long two years from the murder of Emmett Till in 1955 to the enrollment of the Little Rock Nine in 1957, and there are a lot of miles between the deep south and Los Angeles. But Hamill’s editorial work in the King’s Business declared Biola’s position on Christian faith and race relations at a time and place when it obviously mattered. When I read Biola history, I’m not searching for heroes and I’m not expecting to find perfect performance at all times on all issues. I’d like to know a lot more about the institution’s attitude on social issues in the late 1950s as it moved from the urban core to the distant suburbs, since there is such a thing as white flight, elusive though it sometimes is. But I’m glad that these editorials, from exactly the same time as Biola’s move from Sixth and Hope to Biola Avenue, show alertness to racial issues, compassion for black victims of injustice, and the desire to be governed by biblical and spiritual standards.

Although this blog post is mainly about Biola’s editorial judgments in its official publication, the King’s Business, I don’t want to miss the opportunity to document the reader reactions. These reactions, some of which the editors chose to publish in the months following the editorial, give us a certain cross section of Biola’s constituency in the late 1950s. As Mullin noted above, it’s mostly not pretty, especially at first.

From the December 1957 issue:

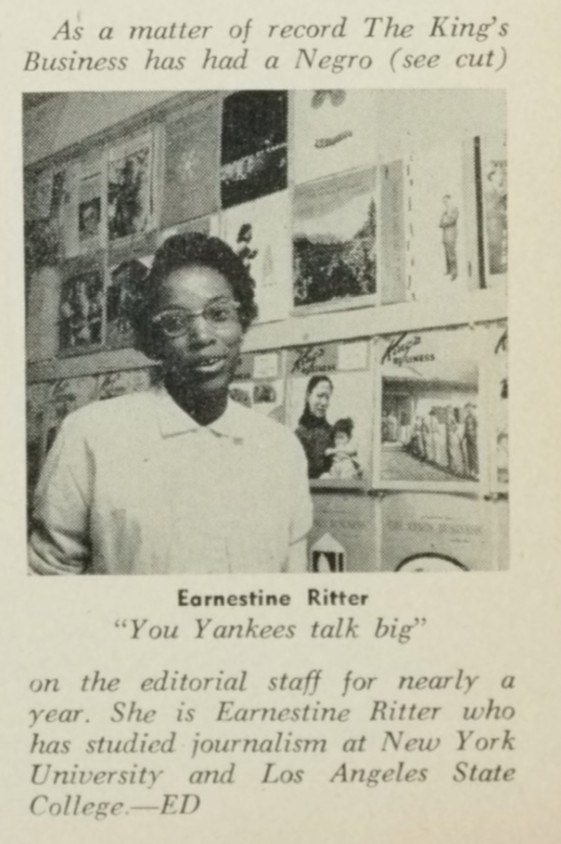

[Paging Earnestine Ritter. Anybody know anything about her? I’ve found references to the following two articles: Earnestine Ritter, “The Negro Takes Strides,” California Sun Magazine 11 (Fall and Winter 1959-60); and Earnestine Ritter, “The Holy Ghost Fell: The Church of God in Christ,” World Pentecost 1:1 (1971), 8-9. These suggest Ritter kept writing, and had interest in civil rights and black Pentecostalism.]

[Paging Earnestine Ritter. Anybody know anything about her? I’ve found references to the following two articles: Earnestine Ritter, “The Negro Takes Strides,” California Sun Magazine 11 (Fall and Winter 1959-60); and Earnestine Ritter, “The Holy Ghost Fell: The Church of God in Christ,” World Pentecost 1:1 (1971), 8-9. These suggest Ritter kept writing, and had interest in civil rights and black Pentecostalism.]

From January 1958:

From February 1958:

From March 1958:

[I wrote this post in April 2016 and updated it in April 2018 because two things had changed: Laats’ important book has now been published, sharing the story more broadly, and Biola’s King’s Business archive has now come online, making it easier to grab screenshots of letters to the editor.]

[I wrote this post in April 2016 and updated it in April 2018 because two things had changed: Laats’ important book has now been published, sharing the story more broadly, and Biola’s King’s Business archive has now come online, making it easier to grab screenshots of letters to the editor.]

Thanks to Marc Malandra for pointing out the Mullin article, Daniel Chrosniak for scanning the dusty old microfilms before the digital archive was online, and Matthew Jones for conversations on white flight in Southern California churches. Jones is crowdfunding his research on this subject, and right now happens to be a strategic time for interested parties to help him out.]