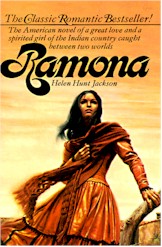

What’s the most popular and influential book in the history of California? An 1884 romance called Ramona, by Helen Hunt Jackson.

What’s the most popular and influential book in the history of California? An 1884 romance called Ramona, by Helen Hunt Jackson.

It’s a longish book that follows the misfortunes of a beautiful young orphan who is half Scottish and half native American. She is raised by the Spanish rancheros of Alta California in the days before the Americans had fully infiltrated the region. She falls in love, suffers a deep loss, and falls in love some more. All through the book, the real star is the romantic landscape of southern California. And the real villain is racism in general, but bigotry against native Americans in particular. “Subtle” is never an appropriate word for the effects that Ramona achieves.

As a Californian (born here, lived here more than half my life) who teaches great books, I could wish for a different book to point to as California’s bestseller. But what we’ve got is Ramona. Couldn’t we at least have some Steinbeck or London as our bestselling classics? While they’re not exactly Homer, at their best they’ve got a little more going on than a romance novel that seems hopelessly dated and Victorian to us now. California surely deserves a better novel as anchor for such literary regionalism as it has, doesn’t it?

But perish the thought: To wish for a better past than the one we’ve got is a very Californian thing to do, and I mean that as an insult. One of the odd features of California culture is that it either has no past, or a fake one. And that makes Ramona the perfectly appropriate novel for us.

“The most important woman in the history of southern California never lived. Nor has she yet died,” says Dydia DeLyser at the beginning of her book Ramona Memories: Tourism and the Shaping of Southern California. DeLyser’s book tells the fascinating story of how Helen Hunt Jackson told southern California’s story in a way that captured the imagination of the world, and drew tourists and immigrants from across America to come to “Ramona country” and see the places they read about in the novel.

It was a remarkable industry, and southern California still has the name Ramona written all over it: towns and farms and roads and products and land developments are all named after Ramona. Once you start noticing this, it’s positively spooky how many things are still named for her. Though the memory is finally fading, back in its heyday Ramona apparently drove a lot of tourist business.

Plenty of people were coming just to find the delicious natural terrain that Helen Hunt Jackson, an accomplished travel writer, had conjured: the uncanny southern California sunlight, the pre-pollution atmosphere, the weird Dr. Seussy plants, and the geography that looks like God roughed it in with broad strokes instead of New England fussiness. They were not disappointed.

But even more people wanted to see the twilight of that venerable Spanish-Mexican civilization that was driven out by westward expansion and Manifest Destiny. They were enchanted by the idea that they could come out and see ranchos that combined rustic simplicity with old-world nobility. They were usually more or less disappointed.

And then there were the hordes who wanted Ramona herself: her birthplace, her childhood haunts, her marriage chapel, her mountain hideaway, her other marriage chapel, her grave. The only problem is, Ramona was a fictional character, so no such places existed to visit.

Were these tourists disappointed? Not at all. They, or their welcoming hosts, fabricated a Ramona travelogue that was made to order. Before long, you could visit as many Ramona pilgrimage sites as you wanted. California had its own past at last, complete with characters. But fake.

And if that’s not enough to make Ramona the book that California deserves, as the gigantic fantasy state that everybody loves to hate but hates to love, there’s the equally ironic situation of the author’s intentions for the book. It was written to draw attention to the plight of the native Americans, especially to their bad treatment by the U.S. government. But “indian awareness” doesn’t tend to make it onto anybody’s list of things they learned from Ramona.

Helen Hunt Jackson was already a successful author long before she wrote this novel she is best remembered for. But somewhere late in her life, she took up the cause of native Americans. In her own words, she became what she had previously called “the most odious thing in the world,” that is, “a woman with a hobby.”

Helen Hunt Jackson was already a successful author long before she wrote this novel she is best remembered for. But somewhere late in her life, she took up the cause of native Americans. In her own words, she became what she had previously called “the most odious thing in the world,” that is, “a woman with a hobby.”

She did well with that hobby, though, partly because there was plenty, more than plenty, of mistreatment for her to document, and partly because she was a pretty handy writer. Her major publication in this area was 1881’s Century of Dishonor, a review of American policy toward the Indians. She sent it to every member of congress. Soon she was appointed special agent for the department of the interior, with the charge to do more writing. So she undertook three trips to southern California, and kept writing out sketches of the pitiful remnants of native American culture she saw there.

In 1883 she wrote her “Report on the Conditions and Needs of the Missions Indians,” a platform from which she continued her lobbying. By the way, a significant reform bill was passed in 1891, so in political terms, Jackson was relatively successful.

But it was 1883 when the idea hit her: She could accomplish more for the Missions Indians as a writer than as a lobbyist. She could write the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the native Americans. This was her explicit goal, as she wrote in a letter to a friend: “If I can do one hundredth part for the Indian what Mrs. Stowe did for the Negro I shall be thankful.” She started the novel, under the working title “In the Name of the Law,” and was finished by March 1884.

Certainly Ramona does provide some gripping scenes of the plight of the Missions Indians. But it also makes their way of life seem kind of nice. They seem more romantic than oppressed. There’s a “noble savage” thread running through the book that tangles up the rest of the message, for one thing. And then there are too many layers, which are all to interesting in their own right: Jackson wants to say the Franciscans were pretty nice (though paternalistic), and the Mexicans were pretty nice (though greedy and racist), and that everything was going pretty well until the whites showed up, backed by federal policies that codified injustice. But by the time all of that is sketched in, against the luscious backdrop of southern California, and a tangled love story mixed with a young-half-breed-woman-coming-of-age narrative with all its own ethnic and developmental tensions….

What you’re left with is Ramona‘s real legacy: California is an awesome place and you should come visit it. Make your reservations now! See it all from the comfort of your own automobile! See Ramona’s birthplace! It all got sucked into the maw of California boosterism, at exactly the time that the state was ramping up to sell the rest of America on the benefits of coming out here.

Ramona is still available, in multiple editions. It’s not as popular as it once was, but it’s never been out of print. It’s been made into movies and telenovellas, and there’s even a long-running outdoor stage show based on it, performed every season in Hemet, CA.

Helen Hunt Jackson was already a well-known author when she wrote Ramona, but if she is remembered at all these days, it is only for her final work, which has had such an odd afterlife.

Here are some other Helen Hunt Jackson books:

Father Junipero and the Mission Indians of California: A good short read for a taste of Jackson’s descriptive powers.

Sonnets and Lyrics: Pretty tough sledding.

Bits of Talk in Verse and Prose For Young Folk: My favorite. Perfectly what it is.

The Helen Hunt Jackson Yearbook: Thoughts for the day from HHJ!

Letters from a Cat. Yep. From a cat.