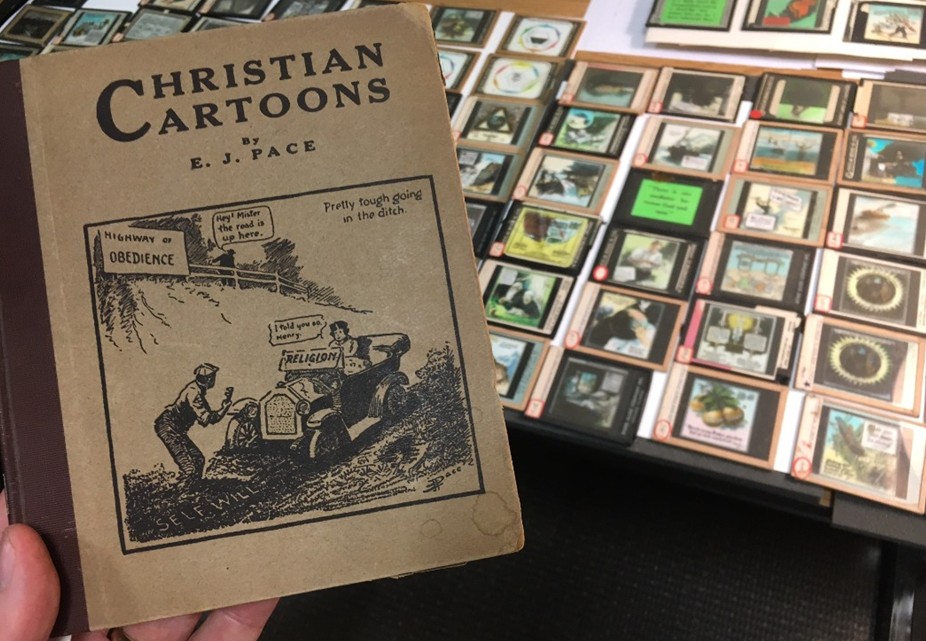

The breaking news part of this post is that Biola library’s Christian Comics Collection, already the deepest archive of its kind, has recently acquired a large set of comics by cartoonist Ernest James Pace (1880-1946).

The breaking news part of this post is that Biola library’s Christian Comics Collection, already the deepest archive of its kind, has recently acquired a large set of comics by cartoonist Ernest James Pace (1880-1946).

This is important because Pace was an early pioneer of Christian cartooning. By adding these Pace materials, the Biola archive has considerably extended its usefulness as a place where scholars can study the early history of the genre. Thanks are due to Nate Butler for brokering the deal: Nate’s tireless work in support of the archive’s goals, travelling the world to network with important cartoonists and their descendants, continues to bring caches of collectibles to light.

The Pace materials deposited in the archive include about three hundred slides (full-color glass film positives for projection) and several hundred original drawings. Many of the drawings have probably never been printed since their original publication in venues like Moody Monthly almost a century ago.

The Pace materials deposited in the archive include about three hundred slides (full-color glass film positives for projection) and several hundred original drawings. Many of the drawings have probably never been printed since their original publication in venues like Moody Monthly almost a century ago.

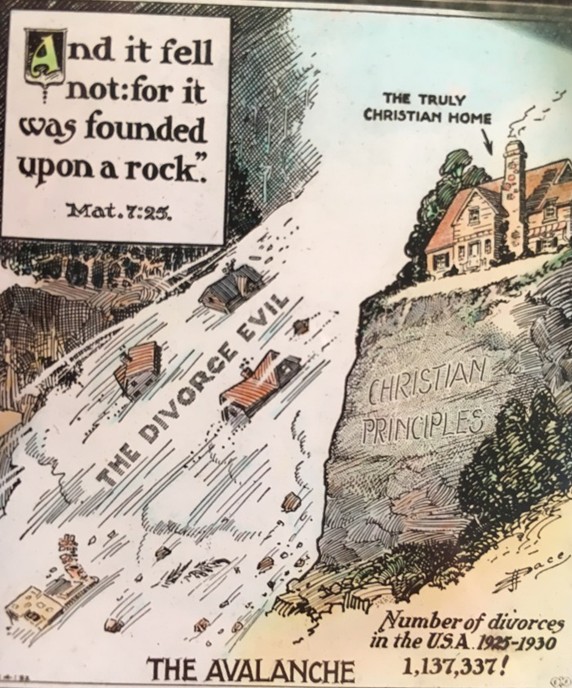

Most people who remember the work of E.J. Pace will think mainly of these editorial-style cartoons that appeared in the more upscale periodicals of the fundamentalist movement. The Biola collection includes a good number of those drawings. It would be very interesting to put Pace’s editorial cartoons in the context of the editorial cartooning being published in newspapers of his time. His drawing abilities certainly measure up to the professional standards of the time, and when I examined these original drawings (which are quite large, often ten inches square) it was easy to see how good an eye Pace had for graphic design, clear communication, and printability of line. The following cartoon (an early 1930s comment on divorce as a social evil) showcases the solidity of Pace’s design: I shot it with my phone camera from a 3″x3″ glass slide. The composition survives all these transfers, and even in this bad jpg you can see that Pace’s lines are crisp:

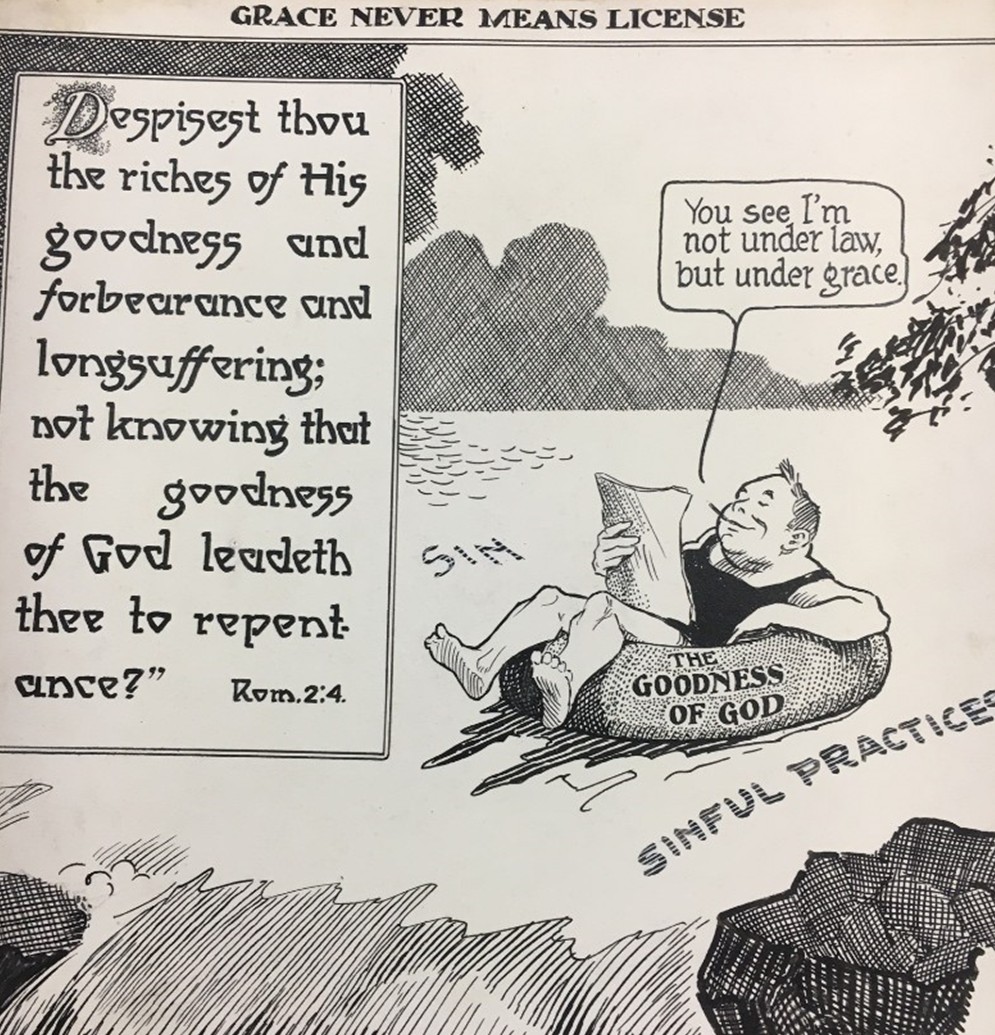

And here is another editorial cartoon (shot from the paper original), directed not at the broader culture but at hypocritical conduct among Christians:

The graphic precision is more evident here: the line-thicness variation is masterful, and extends to the varieties of cross-hatching. The stippling on the inner tube creates a cooler visual field, but also gives way expressively to the shadow of the figure’s arm and feet. Even the incidental touches like the overhanging leaves at the top right show Pace to be a draftsman who delights in observation but requires his drawings to be utterly printable and spare.

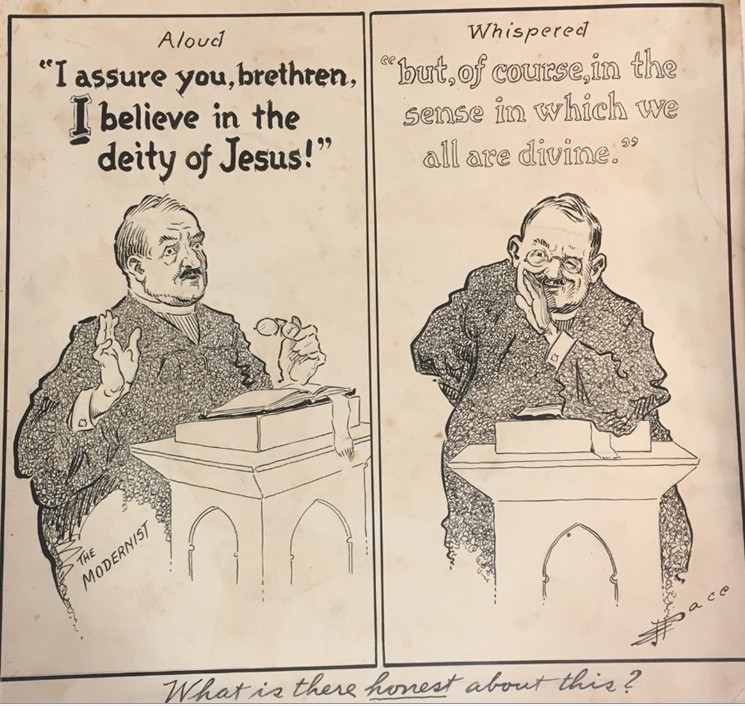

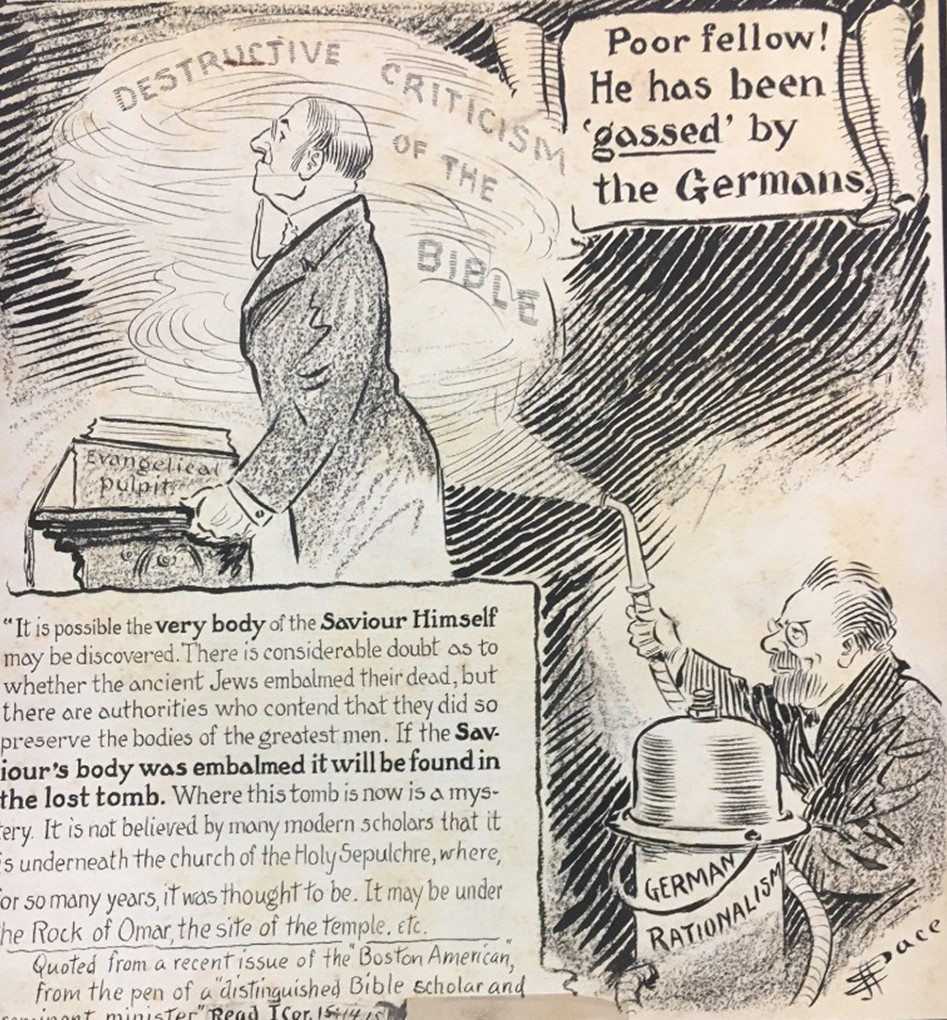

There are also quite a few cartoons devoted to the fundamentalist controversy with the modernists. In particular, Pace obviously relished the chance to print broadsides against liberal theology, exposing the kind of sneaky tricks that modernist clergy perpetrated. Here is one example:

And here is another, associating the heretical views with the influx of skeptical biblical criticism from German scholarship:

This editorializing may seem a bit rough to you, but the reader is entreated to read the fine print and consider the feelings of the Christians of the 1930s as they began hearing these things from their trusted pastors. The treason of the clerics makes for rough play on all sides.

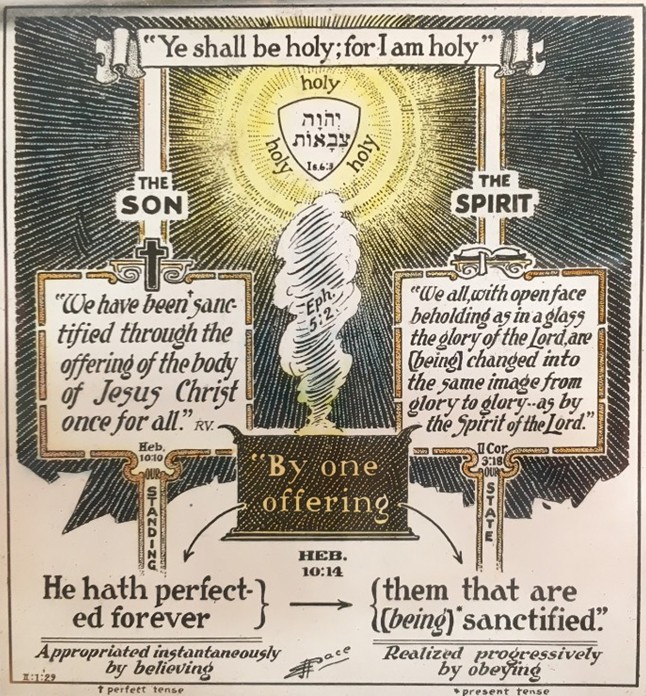

But there are also some surprises in the Pace materials now on file in the Biola archive. Pace had a considerable ministry as a writer and Bible teacher, and a number of the glass slides in this collection seem to be visual aids which he used to communicate Christian doctrine.

Take two examples. In this first slide (undated), Pace is teaching on the nature of holiness. The central visual element is the shining shield of the divine nature, which is holy, holy, holy (a reference to Isaiah 6:3 appears in the bottom of the shield):

But that triune source of holiness is kept in the background because the point of this illustration is actually not divine holiness, but the human holiness that corresponds to it: “You shall be holy as I am holy.” And human holiness comes from the triune God in two ways: by the Son and the Spirit. More to the point, it comes from the “one offering” by which Christ “hath perfected forever” the obedient believers who “are (being) sanctified.” Pace references Heb 10:14 and indicates, by asterisk, that “hath perfected” is in the perfect tense, while “(being) sanctified” is present tense. I think this is the key contrast Pace wants to make in this image: on the left is the work of the Son which affects our standing in holiness before God (see the word descending on the column to the left of the altar), “appropriated instantaneously by believing;” on the right is the work of the Spirit which brings about our state of holiness at any time, “realized progressively by obeying.” The columns display the texts of Hebrews 10:10 (on the left: we have been sanctified by one offering) and II Cor 3:10 (on the right: we are changed from glory to glory). Between the pillars, a cloud of incense ascends from the altar up to God: It is labelled Ephesians 5:2 (“Christ loved us and gave himself up for us as a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God”).

There’s a lot going on there! But the overall image is not cluttered; Pace has subordinated the details to the central idea in such a way that the image opens up for closer study. This is remarkable visual teaching.

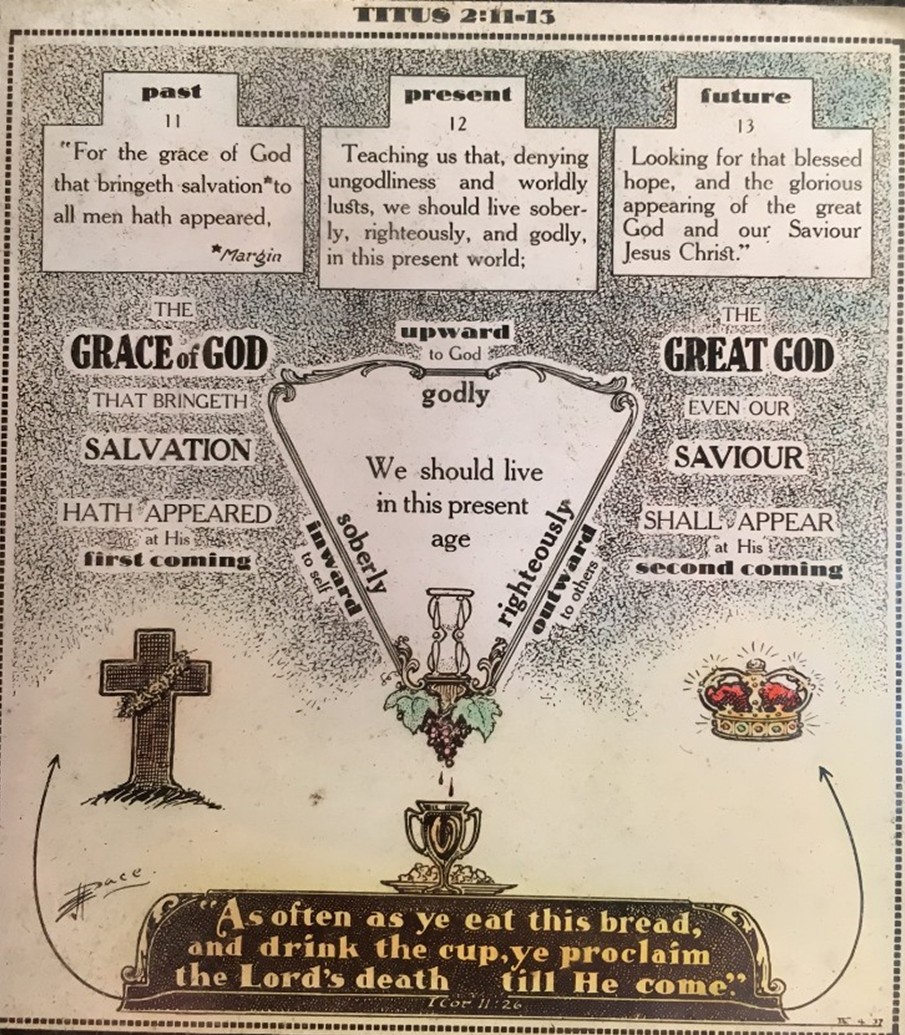

In this second illustration, it is more obvious where Pace got his initial idea. It is from one text of Scripture. He takes the remarkable sentence in Titus 2:11-13 and divides it into past, present, and future phases. This he prints in blocks at the top, and then breaks out into headline summaries in the middle register of the page:

Within the past-present-future triad, Pace expands the middle triad, present, by introducing an upward-inward-outward triad. That is, between the first coming of Christ and the second coming of Christ, we live “in this present age” in the way grace instructs us to: The three adverbs godly-soberly-righteously relate to the up-in-out dimensions of present life. The fact that Pace locates all this in a triangular diagram between past and future enables him to elaborate on the virtues without cluttering the temporal structure of the verse. Then, with less obvious connection to Titus 2, but probably provoked by the idea of doing something now that looks both backward and forward, Pace introduces in the bottom register Paul’s words about the Lord’s supper from I Cor 11:26: “As often as ye eat this bread, and drink the cup, ye proclaim the Lord’s death till He come.” More details could be pointed out: The sands of time in the hourglass of the present age seem to flow into the crushed grapes of the cup of communion. But again, the graphic design of the piece, and the stippled zone above contrasting with the white space below, keep the details from rioting against orderly communication.

None of this theological and Biblical teaching matters much to people who aren’t interested in theology and Bible for their own sake. And Pace’s pedagogical diagrams were understandably less popular than his editorial cartoons. But taken together, they show E.J. Pace to be a fascinating and highly skilled visual communicator of Christian doctrine. Now that such a large cache of Pace’s cartoons are safely archived in the Biola library, his contribution can be studied in detail and placed in context in the early history of Christian cartooning.