Talbot School of Theology’s Master of Arts in Classical Theology is mostly composed of three kinds of courses: Commonplaces (major doctrines); Master Practitioners (significant theologians); and Sacred Page (books of Scripture). Since the entire MA is designed to treat Scripture as “that toward which all studies in divinity move,” these Sacred Page courses are especially important for us to get right. My first opportunity to teach one of them is our Ephesians course.

In this course, our main strategy for studying the book is the immersion method of re-reading: we’ll get through the book 70 times as part of our preparation for weekly discussions. Our pedagogy is discussion-based, so this immersion-plus-discussion dynamic is center stage. We proceed through Ephesians at the rate of about half a chapter per week (1:3-14 gets two weeks).

After text, commentary: For the Spring 2021 version of the course, I’m capitalizing on the fact that there are two excellent, brand new Ephesians commentaries available: Lynn Cohick’s NICNT entry represents the historical-grammatical guild informed by social history, and Mike Allen’s Brazos volume speaks for the movement sometime called the theological interpretation of Scripture. You might expect the schools of NICNT and the Brazos Theological Commentary to clash, but my impression so far is that these two volumes are pretty companionable, partly because of Cohick’s and Allen’s scholarly breadth and temperaments, and partly because of the uniquely focused character of Ephesians itself.

And then, after primary-text immersion and modern commentary, we come to the showpiece of the course: older commentary.

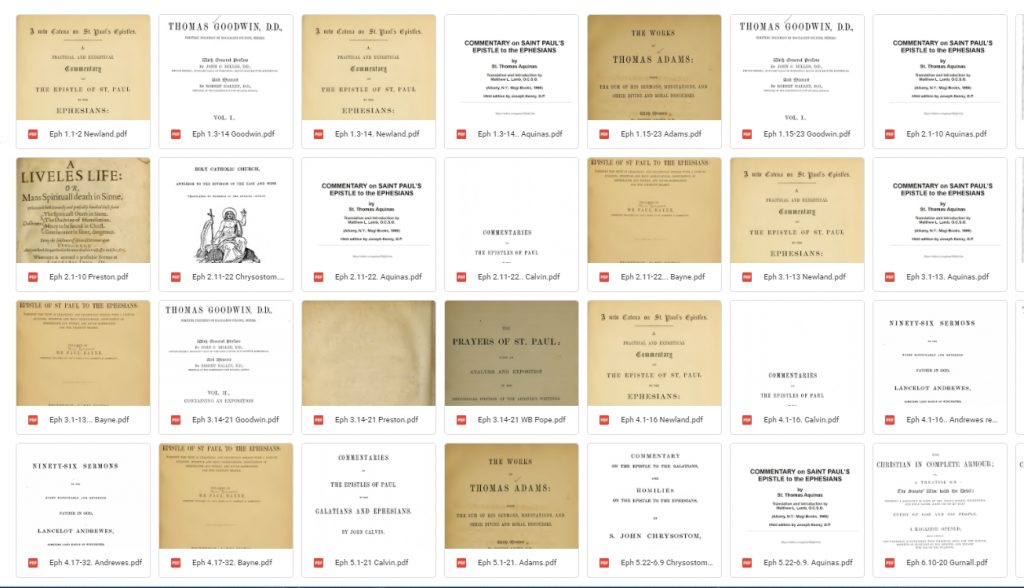

Here’s the hit list, with links to pdfs of assigned selections when possible (so you can read along at home):

Ephesians 1:1-2: Just a few pages from Henry Newland’s 1860 catena of comments (including sources like Origen and Jerome, hard to find in print). Newland weaves together earlier sources judiciously, and proceeds by quotation. This makes his volume a bit like IVP’s Early Christian Commentary series, but with a stronger focus on exegetical argument than on illustration. He’s a raging Arminian who Spurgeon recommends consulting “with discretion.”

Ephesians 1:3-14: About a hundred pages from Thomas Goodwin. If I could do a whole course of just Goodwin on Ephesians, I would. He saw deeper into this book than any other commentator, and when he goes fifty pages on a single verse, you don’t get the feeling that he’s running out of gas. On the contrary, you get the feeling that he could, and should, just keep going.

1:3-14: Another fifty pages from Newland’s catena.

1:3-14: The relevant section of Thomas Aquinas’ Ephesians commentary (I’m linking to an online source for it, since copyright is unclear). Aquinas is always rather surprising to me. His selection of key ideas is not always what I would expect. He is especially good at organizing concepts clearly.

Ephesians 1:15-23: Thomas Adams’ sermon on 1:18, “Spiritual Eye-Salve, or, the Benefits of Illumination.” Some people call Adams (1583-1652) the “Shakespeare of the Puritans,” but I think they just mean he’s very good with words. And he is! This is just 14 pages; you should look into it. It’s eye opening, you might say.

Another hundred pages of Goodwin, because I can. And at 200 pages, we’re still reading less than half of what he wrote on Ephesians 1. Riches on every page. Goodwin on Ephesians has to be experienced to be believed.

Ephesians 2:1-10: Again, the relevant section of Aquinas’ commentary.

James Fergusson, 15 pages from his Exposition of Paul’s Epistles. Fergusson (1621-1667) excels not so much at exposition of how the text runs, as at paraphrasing a passage into doctrinal teaching and spiritual application, clearly labelled as such. We’ll see this style also in Bayne, but Fergusson is more concise and pointed. And the occasional Scottish bit keeps you on your toes.

John Preston (1587-1628), “A Liveles Life, or, Man’s Spiritual Death in Sin.” A profound meditation which sticks close to Ephesians 2:1-3 at the beginning, and then launches out into further teaching on mortification. I cut off the assignment after about 40 pages, as Preston got further from the text.

Ephesians 2:11-22: Our reading on this passage happens to track through a pretty good survey of big names in the history of interpretation: We stop in the fifth century, the thirteenth, the sixteenth, and the seventeenth. Chrysostom’s sermons. We get quite a bit of Chrysostom elsewhere in the course (especially in Newland), but a few times we go directly to his influential sermons to experience the flow of his exposition.

Again, Thomas Aquinas on the same passage. (I considered assigning his entire commentary, but settled for selections instead.)

Calvin’s commentary on 2:11-22. If you want to dig deeper into Calvin on Ephesians, be sure also to check out his sermons on it, which are available in a large volume. Compared to them, his commentary is lean and incisive.

Paul Bayne’s commentary on the same passage. Bayne (1573–1617) will be a reference point for a number of later commentators, especially Goodwin. Again, since Bayne covered everything (in pretty good depth), we could read straight through his work, but I’ve chosen just to dip in at a few points.

Ephesians 3:1-13: Newland’s catena again, for breadth, followed by Aquinas on the relevant portion, and Bayne and Fergusson for the Protestant follow-up.

Ephesians 3:14-21: We get to come back to Goodwin again here, because even though his major work on Ephesians never got past 2:10, he did a sermon on “Christ Dwelling in the Heart” which is an absolute classic.

But the big assignment (about 85 pages) of the week is John Preston’s treatise on The Saint’s Spiritual Strength, in which he starts from Eph 3:16 and expounds a set of signs and tests by which a believer can know the reality of spiritual transformation.

The great Methodist theologian William Burt Pope wrote a book about Paul’s prayers, from which I take the chapter “The Indwelling Trinity,” a profound explanation of this prayer.

Ephesians 4:1-16: A section of Newland’s catena, followed by Calvin’s comments, and then a surprise: a sermon by Lancelot Andrewes, on Psalm 68:18. But Andrewes preaches it as a Pentecost prophecy, and interweaves it with Paul’s quotation of Psalm 68 in Ephesians 4. In any other curriculum, Andrewes would be a dazzling standout for his wordplay and textual fascination, but in this curriculum we’ve already met Goodwin and Adams. Andrewes still stands out, but not by as much as he otherwise would.

Ephesians 4:17-32 gives us another brief visit with Goodwin, a second sermon by Andrewes, and a stretch of Bayne’s commentary. As we get into the second half of the letter and our semester, we won’t meet many new faces for a while.

Ephesians 5:1-21: We read Calvin, and a long sermon by Adams.

Ephesians 5:22-6:9: Chrysostom and Aquinas.

Ephesians 6:10-20: William Gurnall (1617-1679) wrote a vast amount on this passage in his three-volume The Christian in Complete Armor. We read a hundred pages or so, from the very beginning and from near the end of his great work.

Ephesians 6:21-24: Most commentaries run out of steam by here, but Gurnall did not: He gives us over forty pages on these final few verses, and it turns out they well deserve the attention.

That’s our reading list. Recall that on given week, we’re not only reading these classic, older sources, but the matching portions of Cohick and Allen. And then the discussion is centered on What Ephesians Itself Means, using the great cloud of commentators as helpers.

Though I’m thrilled with this list of readings, it is constrained by several limitations. For one thing, even in a reading-heavy course, students can only read so many pages per week. Another limitation is that for older sources, we’ve got to have modern editions and English translations of them (so no Marius Victorinus, no Zanchi, no Poole), and these need to be either affordable or public domain (so Origen/Jerome is out). The texts need to have been printed legibly in the first place and scanned decently afterwards (we lost Hemmingsen and Lancelot Ridley on these counts: just too hard on the eyes). And since Greek is not a prerequisite for this course, I avoided commentaries that interact closely with untransliterated Greek words (Erasmus, Bengel).

That’s a lot of cuts. But what’s left is plenty to keep us busy, and to drive us to interact with God’s word in Ephesians. Our MACT program is necessarily somewhat experimental, and my first time teaching Ephesians at this level is doubly so. But it is an experiment with unfailingly rich elements, and seventy times through Ephesians along will be a significant life experience.