This is my last post in a series of theological preparations for Easter. The first post was about God experiencing death on the cross, and the second was about the two natures of Christ.

This is my last post in a series of theological preparations for Easter. The first post was about God experiencing death on the cross, and the second was about the two natures of Christ.

I’m not trying to clutter up your Holy Week with theology homework. I hope you’ll be attending special services at church, and that the things you’ll be hearing and seeing and feeling will be stirring up deep spiritual reflections. When that happens, I hope to have stocked your mental shelves with some resources to deepen your encounter with Jesus in his holy mysteries. The resources I have to share are classic conceptual categories and distinctions. In this post, the distinction is the Trinitarian one, the distinction between the Father and the Son.

First, try thinking about the cross without making use of any Trinitarian distinctions. This is not a trick assignment; I really mean it. It’s surprising how far you can get if you keep the Trinitarian distinction to one side and just ponder the cross as the one, unified work of God for our salvation.

In the crucifixion of Christ, what God is doing is providing propitiation for sin. Propitiation is a fusty old word, I admit, that most people only know from the Bible. But it’s not only a Bible word: it’s got a pagan background as well, anywhere that any culture has tried to modulate its relationship to a god. Gods have wraths, and worshipers offer sacrifice to turn aside that wrath. That’s just how things work in the religious history of the human race as we know it from a wide variety of ancient cultures.

In the Bible, however, in the Old Testament as well as in the New, propitiation happens with a strange twist. The God of the Bible takes responsibility for making propitiation. Instead of leaving his worshipers to find and offer a sacrifice that would avert his wrath, in Scripture God provides the means of propitiation: “I have given it for you,” he says of animal sacrifice, “on the altar to make atonement” (Leviticus 17:11). This changes everything about propitiation, because it means that instead of standing over against God trying to broker a deal, Biblical worshipers are already caught up in some dynamic that is somehow inside of God’s own deliberations about them. God sees the problem, provides the solution, and draws us into participation in that solution.

And that’s just the Old Testament foundation. By the time God unfolds its inner meaning in the form of the New Testament fulfillment, we have a doctrine of propitiation that John Stott has summarized has “God himself gave himself to save us from himself.”

Stott knew what he was doing when he paraphrased it this way: the idea that we need to be saved from God is a startling way to draw attention to our plight as sinners. But that’s the bad news in a nutshell: our sin puts us in the position of enemies to God. It’s a bad idea to have powerful enemies, strategically speaking. And when your powerful enemy is not only all-powerful but also absolutely right in his grievance against you, you have no ground to stand on and no basis for appeal.

So “God himself gave himself to save us from himself.” The sin problem runs deep, and can only be dealt with if several things happen at the same time. God has to confront it face to face, but also cast it away from his presence. He has to bear it and bear it away. He has to take it in but simultaneously expel it. God is absolutely holy and utterly merciful at one and the same time, and the cross is the conspicuous display of both facts.

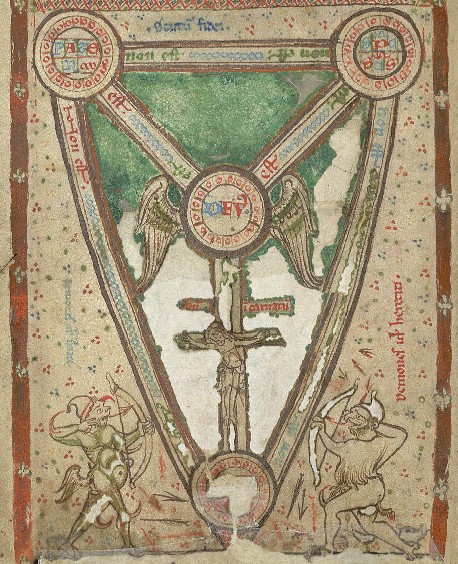

Now cue the Trinitarian distinction. The Father sends the Son to take up human nature. Together in the unity of the Holy Spirit, the Father and the Son grasp the sin problem from both sides and do what needs to be done. In one inseparable action, the Son takes hold of human nature in its sinful depths and the Father pronounces judgment on it. In one inseparable action, the Father exiles sin and the Son repents on behalf of his brothers. In one inseparable action, the Father metes out righteous punishment and the Son cries to him from his human nature for human salvation.

In the Bible, punishment takes the form of suffering, exile, or compensation. On the cross we see the human suffering of the divine person. From the cross we hear a shout from the land of exile (“why have you forsaken me?”). At the cross we know that compensation has been made in the currency of the incarnate Son’s personal fortune, which is the same wealth as the Father and the Spirit.

On Good Friday you sometimes hear preachers hint that the Trinity got fractured at the cross, as if something ruptured the relationship between the Father and the Son.

Nonsense.

The cross didn’t break the Trinity. The Trinity broke sin at the cross, in one inseparable operation of the holy and merciful Father, the holy and merciful Son, and Holy and merciful Spirit.