The doctrine of salvation can hardly be unfolded more grandly or clearly than in the terms of adoption: that God pays the price of accepting sinners into the life of sonship; that becoming like Christ means having his Father as our Father, his Spirit of sonship as the Spirit of our sonship; that the eternal Son became the incarnate Son to make adopted sons out of rebels; that what we are saved to is not just the cancellation of what we are saved from, but a gift and status incomprehensibly high; that our union with Christ is incorporation as co-children, co-inheritors, co-dwellers in the household of God the Father, as brothers and sisters of the Son and of each other. Once the truth of adoption gets a grip on you, the four gospels fly open to reveal not just isolated vignettes of Jesus story-time, but the steady display of the relationship of the Son to the Father, into which we are miraculously transported by no merit of our own, but at great cost to God.

The doctrine of salvation can hardly be unfolded more grandly or clearly than in the terms of adoption: that God pays the price of accepting sinners into the life of sonship; that becoming like Christ means having his Father as our Father, his Spirit of sonship as the Spirit of our sonship; that the eternal Son became the incarnate Son to make adopted sons out of rebels; that what we are saved to is not just the cancellation of what we are saved from, but a gift and status incomprehensibly high; that our union with Christ is incorporation as co-children, co-inheritors, co-dwellers in the household of God the Father, as brothers and sisters of the Son and of each other. Once the truth of adoption gets a grip on you, the four gospels fly open to reveal not just isolated vignettes of Jesus story-time, but the steady display of the relationship of the Son to the Father, into which we are miraculously transported by no merit of our own, but at great cost to God.

Though the doctrine of adoption may never have occupied as conspicuous a place in systematic theology as it deserves to have, it still shines out even when assigned a less prominent place. If you read around in the right books of theology, you’ll find almost extravagant praise for the doctrine of adoption: it is the Christian’s “great and fountain privilege, flowing from the love of the Father,” as John Owen says; it is “the crowning blessing, to which justification clears the way,” as J. I Packer says.

So I find it almost unthinkable that anybody could oppose this doctrine. When I teach on the subject in a variety of Christian churches, I assume I might have the opportunity of being the first person to lead my listeners in surveying its wonders, but never that I might need to convince a hostile crowd. I assume the doctrine may have been neglected, but hardly rejected.

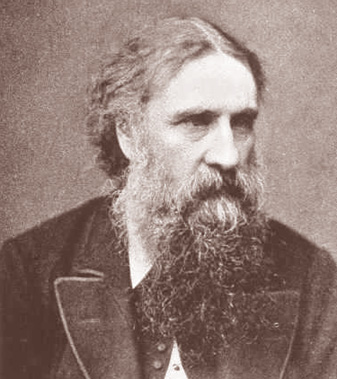

Yet there is one writer who hated it. And he’s not just anybody. He’s George MacDonald, a great soul who I consider an indispensable guide to some of the depths of the Christian message, a unique and irreplaceable example of how God’s love can nourish the Christian imagination. And MacDonald didn’t just prefer to avoid the terminology of adoption; he actively abominated it, lashed out against it, strategically undermined it in the mind and heart of anybody he could influence. So anybody who loves both MacDonald and adoption has a choice to make here. It’s not a choice to abandon reading MacDonald (nobody else has Curdie, Diamond, the Light Princess, the Wise Woman, those lightning flashes of insight in the sermons, that whole-souled recumbence on the everlasting arms). But it’s the choice to read MacDonald with more critical reserve, with eyes wide open to the fact that he erred on this subject, a subject that can’t finally be isolated from a host of others. You can’t have both a thoroughly MacDonaldite account of the faith, and also the soteriology of adoption.

No, MacDonald hated the thing he ridiculed as “the so-called doctrine of Adoption,” because he considered it spiritually disastrous for anybody to be in the position of regarding God as ever having been anything but their Father. Adoption, taken literally, means moving from a state of not having God as your Father, to a new relation in which God begins to be your Father. In his sermon “Abba, Father!” (in Unspoken Sermons, second series), MacDonald puts it this way:

When a heart hears–and believes, or half believes–that it is not the child of God by origin, from the first of its being, but may possibly be adopted into his family, its love sinks at once in a cold faint: where is its own father, and who is this that would adopt it? To myself, in the morning of childhood, the evil doctrine was a mist through which the light came struggling, a cloud-phantom of repellent mien–requiring maturer thought and truer knowledge to dissipate it.

What MacDonald is doing here is thinking through the truth of God’s fatherhood from the point of view of the child, from the center of the emotional life of the one who is calling “Abba.” And what he finds is that the luminous good news of adoption conceals within itself a very dark preliminary of intolerably bad news: thou art not God’s child until this adoption takes place. Speaking as the child (whose “love sinks at once in a cold faint” at this distressing message), MacDonald cries out:

‘Is God then not my Father,’ cries the heart of the child, ‘that I need to be adopted by him? Adoption! that can never satisfy me. Who is my father? Am I not his to begin with? Is God not my very own Father? Is he my Father only in a sort or fashion–by a legal contrivance? Truly, much love may lie in adoption, but if I accept it from any one, I allow myself the child of another!

The nub of MacDonald’s objection is that God simply must already be his Father, always already his Father, never not his Father. To accept adoption would entail first accepting utter estrangement from the source of being; a total renunciation of what you essentially are; a complete, cosmic, metaphysical disowning and abandonment: Fatherlessness in the absolute sense! News like this, it seems to MacDonald, is so devastating that the supposed “good news” of adoption always comes too late and says too little:

‘Alas!’ cries the child, ‘if he be not my father, he cannot become my father. A father is a father from the beginning. A primary relation cannot be superinduced. The consequence might be small where earthly fatherhood was concerned, but the very origin of my being–alas, if he be only a maker and not a father! Then am I only a machine, and not a child–not a man! It is false to say I was created in his image!

Here, I think, we catch a glimpse of the mistake lurking under MacDonald’s heartfelt objection. He assumes that the creator must necessarily be a father, that the origin of our being cannot be anything other than the father of our being. If God is “only a maker and not a father,” then, MacDonald supposes, the consequence is that the human person is “only a machine and… not a man.” MacDonald didn’t extend this to the non-human creation (“I have nothing to argue from in the animals, for I do not understand them”), but when it comes to humans “created in the image of God,” he believes they are necessarily God’s children.

“But creation is not fatherhood,” you may want to object. MacDonald prints this objection and immediately meets it: “Creation in the image of God, is.” This is just a mistake, and I’m glad MacDonald was straightforward about it rather than sneaky. Christian theology has deep reasons for distinguishing between creation and fatherhood. Set aside for a moment the actual biblical usage of all the words related to fatherhood; a careful study of them reveals the incredible specificity and reserve by which they are governed throughout Scripture. In the history of theology, though, Athanasius explained why Jesus’ status as “son of God” necessarily entailed his full divinity, his full participation in the very being of God: God creates things that are not of his own nature, but Fathers only that which is of his own nature. Just as “a man by craft builds a house, but by nature begets a son,” God the Father eternally begets God the Son, of one nature with himself, but by craft makes creatures out of nothing, not out of his own nature. Marking this distinction puts the eternal Son of God at a high place (indeed, coeternal and consubstantial with the Father), makes the Father-Son dyad a unique category in Christian thought, and necessarily moves all created things to a different realm.

The relationship of Fatherhood, in other words, is something God has with the eternal Son, and the good news of adoption is that creatures, mere creatures, are brought into that relationship by being included in Christ, brought into sonship by the one true and proper Son of God. MacDonald probably knows all this but allows himself to forget it as he pursues his intuition that sonship must always belong to human creatures.

The mistake causes many problems for MacDonald’s thought. He has to work hard to explain Paul’s terminology, arguing that “our English presentation of his teaching is in this point very misleading” and that the Greek huiothesia ought to be translated “placed as a son” or “the raising of one who is a son to the true position of a son.” but not as “adopted.” As he reads it, the word “does not imply that God adopts children that are not his own, but rather that a second time he fathers his own; that a second time they are born–this time from above; that he will make himself tenfold, yea, infinitely their father.” This linguistic stretch is not as bad as MacDonald’s habit of avoiding the texts that would most trouble his interpretation. And throughout the “Abba, Father!” sermon, MacDonald indulges in some polemics against “theology” and “systems” that is rhetorically debased and unworthy of a great writer, but is especially unseemly from someone who is manifestly setting out to establish his own theological system equipped with clear enough distinctions to exclude the traditional one.

In his novel Donal Grant, MacDonald puts these arguments in the mouth of his spokescharacter, who says

God’s mercy is infinite; and the doctrine of Adoption is one of the falsest of false doctrines. In bitter lack of the spirit whereby we cry Abba, Father, the so-called Church invented it; and it remains, a hideous mask wherewith false and ignorant teachers scare God’s children from their Father’s arms.

Sharp words, these: “falsest of false doctrines,” “so-called Church.” MacDonald recognizes that if he is right, the message of the Bible has been fundamentally mis-read for a very long time. How long, he will not say; his polemical target is generally the Church of Scotland. But whatever institution has been teaching adoption cannot be the true church, only the “so-called Church.” In the novel, as the radical nature of Donal Grant’s teaching dawns on one of his hearers, she muses, “What if God be sending fresh light into the minds of his people?” In that case, Donal Grant, and his author George MacDonald, would be the prophets of a new kind of church.

George MacDonald was, of course, a pastor ejected from his first church for heresy. As Stephen Prickett notes, “this was a rare enough distinction,” considering “how far the Congregationalists lived up to their other name of Independents on matters of theology.” He would later find a spiritual home in the Church of England under the ministry of F. D. Maurice (twenty years his elder), who would also end up stepping down from the ministry because of his commitment to a tentative universalism. For those who know Maurice’s writings, the MacDonald-Maurice connection highlights just how central for MacDonald is the doctrine of the universal fatherhood of God. On this view, God is universally the Father of all humanity; universal brotherhood of all humans follows from this; and (to their credit) social implications of solidarity and support for the poor were drawn from these tenets. “The Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man” is the rallying cry for the old school of theological liberalism, and when I call George MacDonald a liberal theologian, I don’t intend it merely as an all-purpose insult. The label of “liberal theology” identifies a specific school of thought and a few key doctrinal decisions, chief among them being the universal fatherhood of God. MacDonald was utterly serious in his commitment to that tenet of liberal theology. I don’t know if the error of universalism necessarily follows from that error, but in MacDonald’s case it seems that it did.

MacDonald, in other words, didn’t accidentally reject the doctrine of adoption. He did it on purpose with a full willingness to follow the consequences as he saw them. This is what I want to remain alert to as I continue to read MacDonald. His insight is extremely deep, but also one-sided. His influence on C.S. Lewis is pervasive, and there are two ways of looking at the implications of that: on the one hand, you could say that Lewis transmitted MacDonald’s thought to new audiences. On the other hand, you could say that Lewis spent his whole writing career trying to clean up MacDonald and salvage his usable insights. Either way, whenever Lewis’s orthodoxy is called into question, you can predict it will be in one of the places where he most closely engaged the legacy of his teacher George MacDonald.

For much better instruction on the doctrine of adoption, it’s best to turn to Robert S. Candlish, a wonderful preacher who was a contemporary of F.D. Maurice and who recognized in Maurice’s teaching about God’s universal fatherhood the major spiritual danger of the age. Candlish’s book The Fatherhood of God is a treasure on this subject, filled with surprising light on biblical teaching, deeply informed by traditional Christian theology, and pastorally sensitive even when drawing sharp doctrinal lines. Candlish also has a poetic sensibility and an ability to turn good sentences. He’s no George MacDonald or anything, but who is? And it’s helpful that the most able opponent of the liberal doctrine of God’s universal fatherhood was not prosaic or dry, but wrote a book of beauty and power that just waits to be rediscovered by our own age.