A set of images from the Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves, a Dutch Gothic illuminated manuscript from about 1440 (see below for more information on the source). In a series of nine pages, the artist gives us the legend of the cross, which is a mixture of pious mythology, quaint credulity, a love of good storytelling, and curiosity about biblical history, all cooked up together in the fire of unrestrained devotional intensity. But though it’s a kind of fairy tale using historical characters, the theological intention is pretty clear: the crucifixion of Christ didn’t just suddenly happen. This legendary tale of the pre-history of the cross dramatizes the truth that God’s compassion prepared Christ’s passion from the beginning.

The first image looks like a medieval Dutch interior with twins standing by a bedside. But it’s actually a portrayal of Adam on his deathbed, and the twins are just his son Seth portrayed twice: first leaning over Adam to hear his final request, and then turning to go outside (hat on head, staff in hand) to carry it out. The legend of the cross begins here: Adam in exile, in his final illness, having lived a hard life under the curse to the east of Eden, asks his son to go back to the garden and get a branch from the Tree of Mercy (yes, the belief was that there was a Tree of Mercy; long story). The doubled Seth is cinematic, or perhaps cartoony: we see him juxtaposed with himself, doing two things in one narrative frame.

Out the little window is a tree.

Seth comes to the gates of Eden, where Michael the archangel hands him the branch from the Tree of Mercy. Eden looks like a great place; even the rose-colored wall and gate are the loveliest Gothic architecture, complete with flying buttresses. At the lower left is what I thought was some kind of doggy door, but art historian John Plummer identifies it as an “arched sluice gate” “from which “runs the water from one of the rivers of Paradise,” decorated as “a water wheel turned by a small treading animal on the keystone.” And you can see its reflection in muddy water. Did I mention that these images are about 2.5 inches tall?

When Seth returns home, Adam has died and his body is prepared for burial. Seth gives him the branch of Mercy… by planting it in Adam’s open mouth!

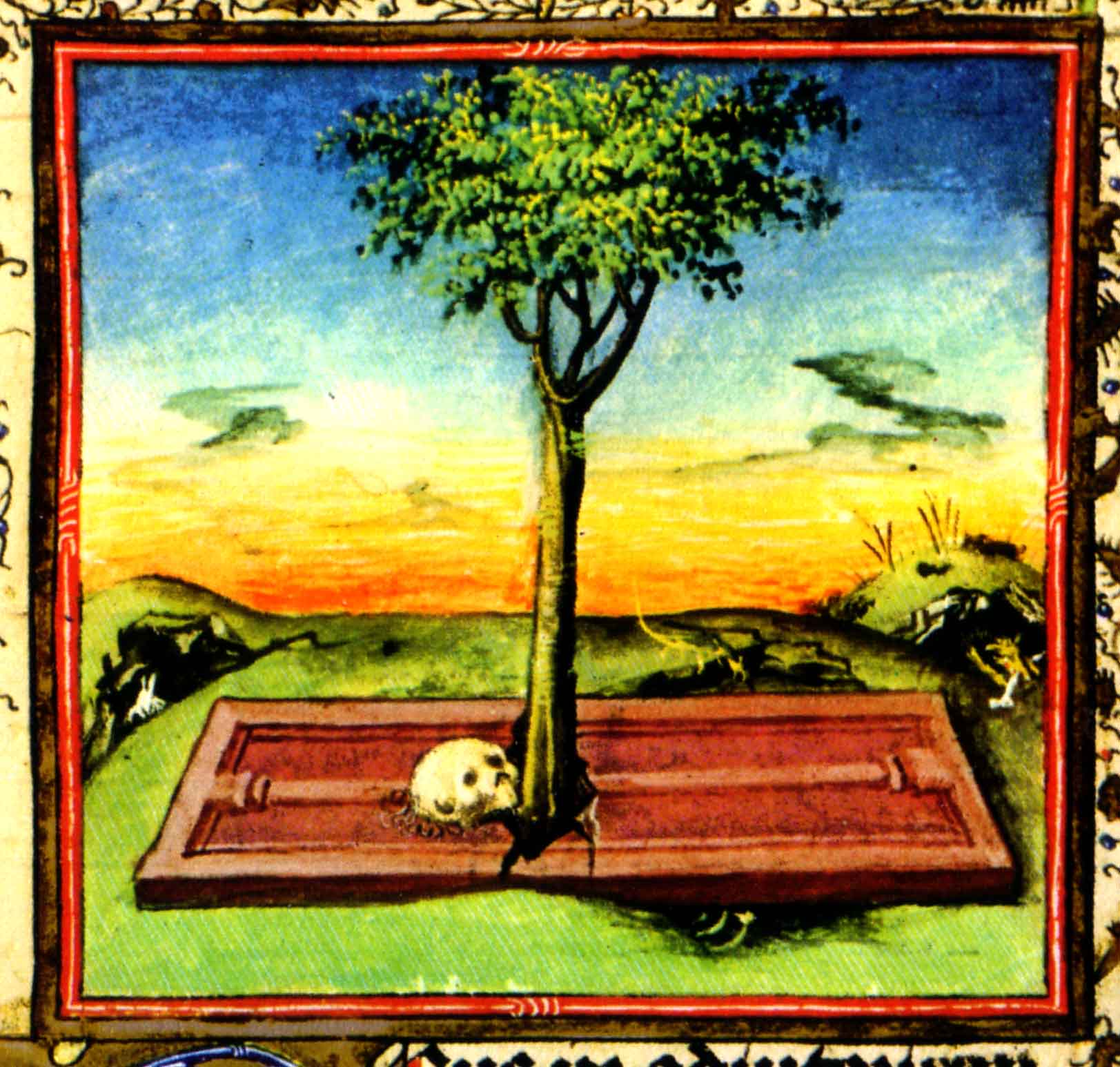

Years pass, and the starter branch has grown into a tree, forcing its way up through Adam’s grave slab and apparently bringing the top of Adam’s skull along with it. There is another legend (this book of hours does not pursue it) that the hill Golgotha, the place of the skull, where Jesus was crucified, is also the place of Adam’s burial. It takes some inventiveness to make that work out (see the description here if you’re interested). Even if that would be too much to read into this image, what we do have is the Tree of Mercy planted in the place of the skull of the first Adam, which is suggestive enough. Below the slab you can see perhaps Adam’s rib cage; under the other hills are perhaps other bones and beasts. So this is a beautiful and colorful landscape, but death lurks underneath every hill.

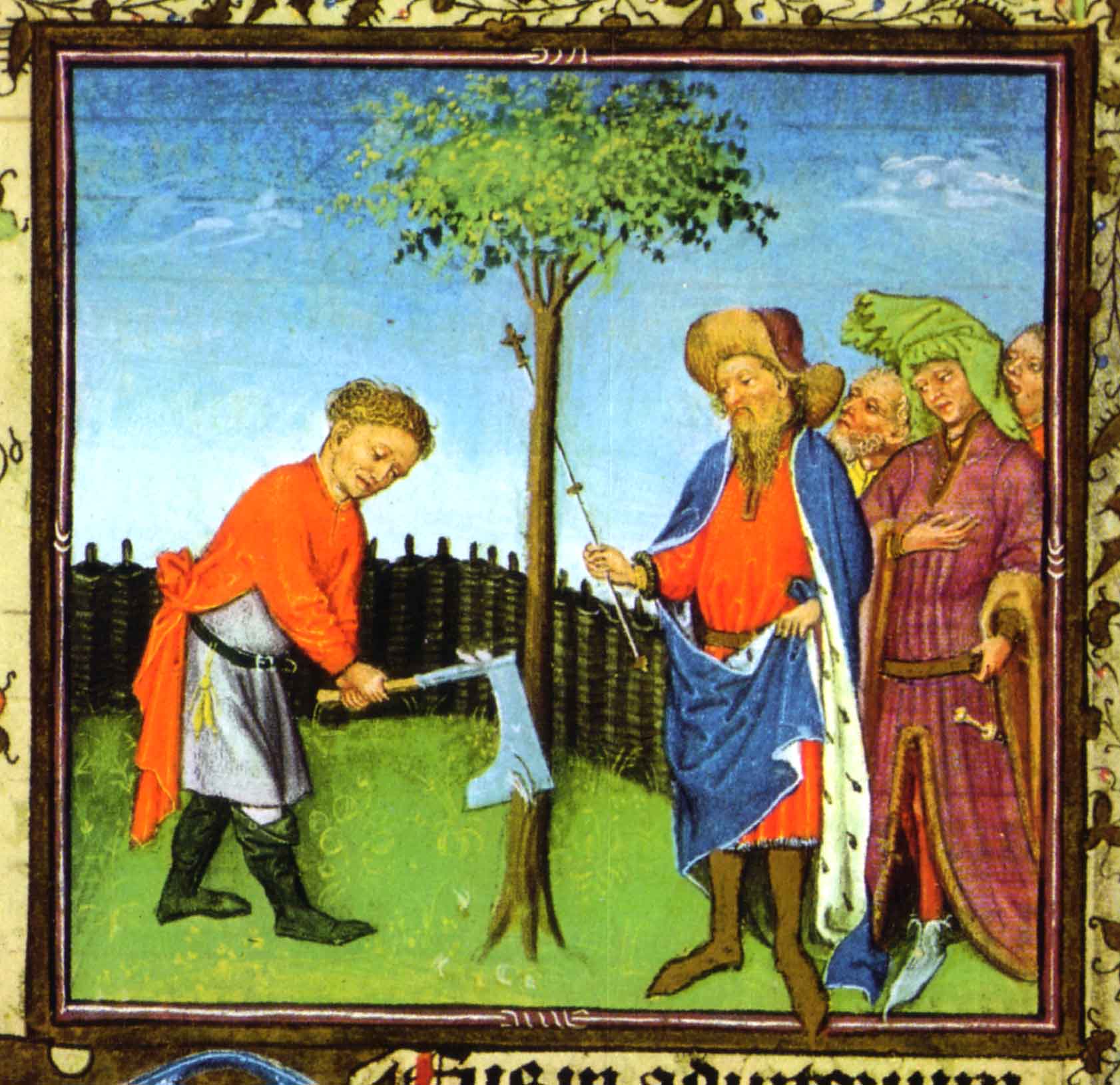

Next comes a three-part series of images having to do with Solomon: that’s him in red and blue, holding the scepter. In this scene he is directing a workman to chop down the tree. He has plans for it.

Solomon directs his worker to timber the tree, planing it into lumber for the temple project.

According to historian John Plummer, the legend of the cross involves a long, suspense-filled story in which the builders of the temple try to use this beam somewhere, but always find it a little too long or a little too short. Ultimately they use it to make a footbridge into Jerusalem instead. When Solomon invites the Queen of Sheba (that’s her with the pillow-hat) to behold the regal splendor of Zion, something prophetic happens: “recognizing it as the wood upon which Christ would be crucified,” she “refused to step on it, and according to one of the many versions of the story, waded through the stream.”

This entire 3-panel Solomon sequence (a third of the whole cycle) may seem like a long digression, but it was a major part of the legend. And it held special significance for a European audience. The Queen of Sheba coming to Jerusalem was the clearest Old Testament example of Gentiles recognizing the God of Israel as the true God. So her presence here, in a devotional book prepared for Catherine of Cleves, a Christian Duchess of Guelders, is a way of connecting the gospel to the Gentile West, to medieval Europe. They were included prophetically in the blessings of the Jews by recognition of the wood of the cross.

This is the pool of Bethesda (John 5), and a very (very!) sick man is being dipped into it for healing. John’s gospel tells us that an angel would periodically “trouble the waters,” and you can see the angel flying in at a strong diagonal angle on the right. But a legendary account also attributed Bethesda’s healing power to the presence of a piece of scrap wood from the Tree of Mercy.

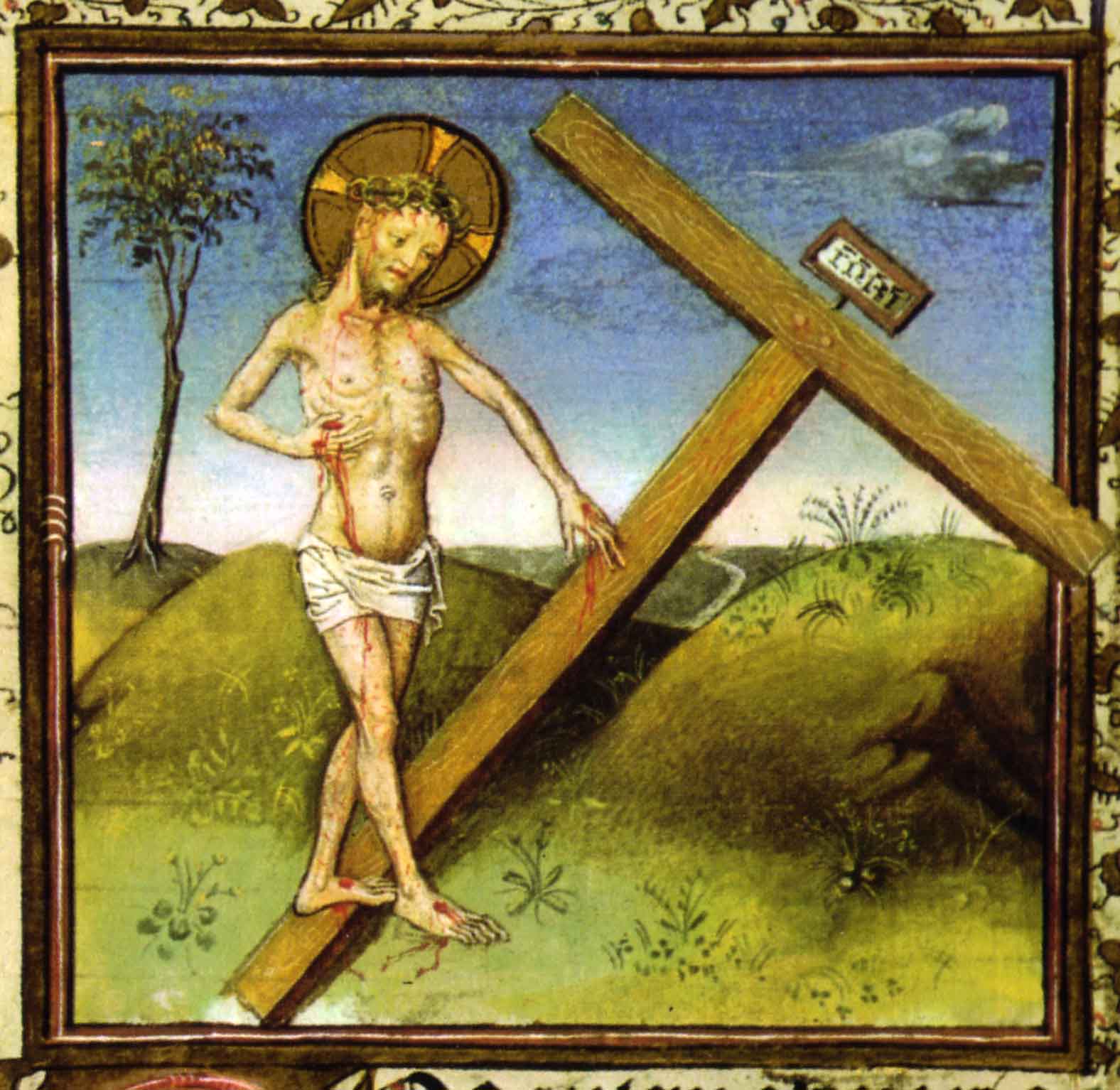

The final image in the sequence shows the crucified and risen Christ, somewhat symbolically: He bears all the marks of death, but stands up and presents himself (emphasizing the side wound which certifies his actual death) while treading down the fallen cross. No such scene ever occurred in history; the artist is not illustrating an event but arranging the symbols of a truth. Christ portrayed in this way (dead but alive, risen yet emphasizing his suffering rather than his mighty victory over the grave) is referred to as the “Man of Sorrows” iconographic type.

These nine images must be viewed in sequence, not isolated. Taken together, they imaginatively fill out, with all kinds of legendary and even fanciful associations, the spiritual reality of God’s long compassion, prepared from the beginning but fulfilled in Christ’s sacrifice.

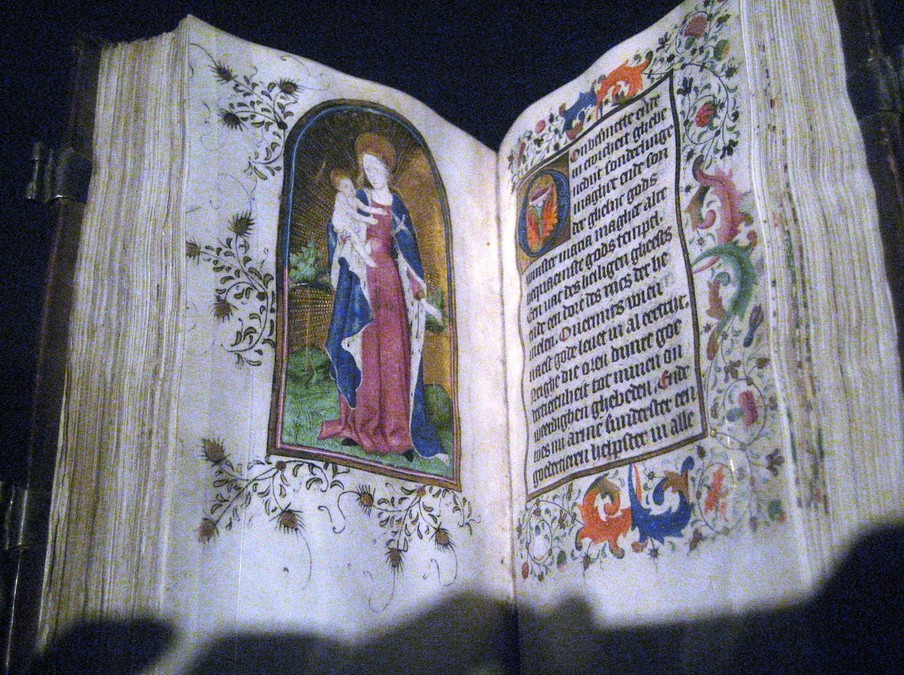

Lost from public knowledge for 400 years, then dismembered and sold as two separate books, BHCC is now reassembled (minus just a few pages) and safe, well cared for and made available for viewing at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. It is small: each page is about 7 x 5 inches. This sequence of nine images is from the “Hours of the Compassion of God,” rendered in this volume as a guided devotion focused not so much on the crucifixion of Christ (for the “Hours of the Cross” sequence with its more traditional visual narrative of the sufferings of Christ, go here)

Lost from public knowledge for 400 years, then dismembered and sold as two separate books, BHCC is now reassembled (minus just a few pages) and safe, well cared for and made available for viewing at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. It is small: each page is about 7 x 5 inches. This sequence of nine images is from the “Hours of the Compassion of God,” rendered in this volume as a guided devotion focused not so much on the crucifixion of Christ (for the “Hours of the Cross” sequence with its more traditional visual narrative of the sufferings of Christ, go here)

The sequence of images above shows just the main illustrations from the center of the pages; the other important elements on the page are elaborate marginal illustrations, decorative flourishes, and of course the main thing the book is for: a lot of text, the traditional prayers and liturgy. You can see the actual page-spread layout here at the left. So the space reserved for the illustration is about 2.5 inches square. These are tiny images, painted on vellum and still exquisitely bright today. The Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves is one of the major pieces of medieval art, and though we know its chief artist only as “the Master of the Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves,” he was evidently a genius of iconographic interpretation.

The sequence of images above shows just the main illustrations from the center of the pages; the other important elements on the page are elaborate marginal illustrations, decorative flourishes, and of course the main thing the book is for: a lot of text, the traditional prayers and liturgy. You can see the actual page-spread layout here at the left. So the space reserved for the illustration is about 2.5 inches square. These are tiny images, painted on vellum and still exquisitely bright today. The Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves is one of the major pieces of medieval art, and though we know its chief artist only as “the Master of the Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves,” he was evidently a genius of iconographic interpretation.