Visiting an art museum can be a stifling experience. No matter how friendly the staff or how hospitable the building itself may be, most of us suffer from an almost palpable feeling of intimidation in a museum.

But you can’t look at all of them, or at least you can’t look at them with as much attention as they apparently deserve. Browbeaten by SHEER GREATNESS, you slink by a Rembrandt or apologize to some Italian masterpiece as you dart through the room, and all the eyes in all the portraits do that freaky “follow you through the room” thing. Surely your inability to give each of these masterpieces the attention they deserve reflects poorly on your own character.

It’s almost a relief when you run into a bad painting (but don’t literally run into it, since unlike the paintings, the guards really are watching you), because for one moment you can exert some sense of superiority to the lousy thing. But then it’s right back to “Sorry, Mr. Van Gogh, excuse me, Mr. Pollaiuolowolo” as you avert your eyes and try to find the exit.

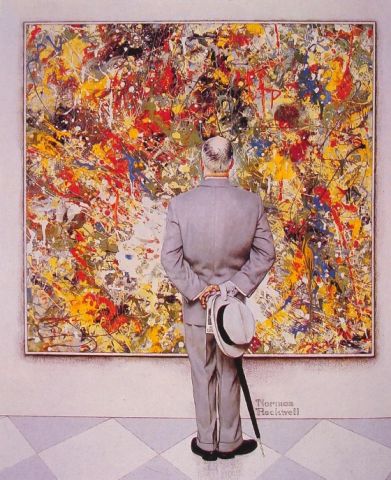

Even more awkward is the moment when you encounter a painting that grips you. For some reason it stands out from the crowd of images you’ve already seen and makes a powerful connection. You like it. It moves you. You’ve seen something new and interesting here. But after about 90 seconds, you have to admit that you don’t really know what to do next.

Other people are standing in front of paintings for five or ten minutes at a stretch, just loooooooking. What are they spending so much time looking at? You really can’t imagine what it is you’re supposed to be doing with your eyes: Blinking? Looking at all four of the corners? Should you hold your thumb up to it? Should you tell yourself a little story about the picture, or pretend you’re a character in it? Count the toes on the people in it to see if the artist messed up? Do I put my hands in my pockets or behind my back while I’m looking? What are the rules? Just what is it that you could be doing if you want to extend this art experience and get more out of a painting that you already like?

A similar question often occurs to me at classical music concerts when I inevitably lose my ability to concentrate on the music and find myself being tossed around on a sea of notes. “Listen more gooder,” I tell my musically illiterate self, but for the life of me, all I can hear is “notes go up, notes go down; notes go up, notes go down.” Over the years, I’ve asked friends and wives (okay, one wife) for helpful hints that can keep me oriented during a long concert.

For museum trips, I have tapped into my training as a visual artist and come up with the following eight tips for how to get more insight into a painting. Try these out next time you’re standing in front of a painting wondering how to make the most of it.

The first three tips help you see the things about the painting that are, paradoxically, too obvious for you to notice. To bring these things to your attention, you need to temporarily turn off some of your mind’s habitual tendency to recognize and label what it sees. You didn’t notice it happening, but by the time you’re standing there thinking about an image, your unconscious mind had already run the image through all sorts of perceptual grids and decided to help you ignore a great deal of the information. Your first three steps, therefore, are backward steps, giving your eyes a chance to reclaim some of that information from your necessary habits of rapidly simplifying all visual experience. So do this:

1. Squint at it. Narrow your eyes enough to blur the image. You need to eliminate the details of the image and try to see nothing but the main colors and forms that are there. If you’re near-sighted, take off your glasses and enjoy the big blurry blob of visual goo in front of you. No matter how detailed or nuanced or textured the image is, the biggest structural design elements are all there to be seen at the macro level. After you’ve seen the total shape without the sharp details, alternate focusing and un-focusing your eyes and notice which elements pop back into your field of attention.

2. Flip it over. A preliminary word: DO NOT LITERALLY FLIP A PAINTING OVER. But turn your head as far sideways as you can. What you want to do here is scramble the information so that it stops making normal sense to you, and begins to make sense as simply abstract shapes. What you couldn’t stop seeing as a boat turns out to be an oblong white shape with a lot of blue in it, against a background which used to just be “the ocean” but now is obviously a blob of paint shaped like a catcher’s glove. Turning a picture upside down shakes all the representational reason out of it and leaves behind nothing but the shapes, lines, and colors that are the real containers of the visual meaning.

3. Find the negative space. “The term negative space …refers to the opposite of solid objects. It describes the spaces left open around the objects and the empty hollows within them.” (Rudolf Arnheim, To the Rescue of Art, p. 92). This stuff is the other half of visual reality, the stuff between all the other stuff, the rest of the jigsaw puzzle. Learning how to see it will open your eyes to the visual structure of the whole composition. Remember that when an artist paints an object against a background, they have to paint the background as well. That background is really a big slab of negative space, a blob of paint with a specific shape. You could cut it out and have a background with a person-shaped hole in it (Do not actually cut out the figure; remember the guards again and the future generations who want to see this painting). Don’t panic if you can’t see negative space yet; it’s a skill worth acquiring, but it takes practice.

The next three tips move from recapturing easily ignored information to analyzing what you’re seeing.

4. Define the moment. Why does this image capture precisely the moment it does? If it were a photo, could it have been taken one second earlier? Ten seconds? Is there a decisive instant in time which the image captures? What is that instant?

5. Re-Construct it. Mentally dis-assemble the art object you’re looking at and ask yourself how it was put together in the first place (Do not actually take apart a painting in a museum). The more you know about the artistic medium used, the better you can do this. But even if you have no experience with oil painting or marble carving, you can learn a lot about an art work by studying it for signs of the craftsmanship that went into it. For all the cerebral and spiritual and illusionistic elements of the visual arts, there is a very important physical side to it as well, and when you can see how the marks were made (varied, layered, mixed, etc.) you can see the piece of art as the product of a performance that once occurred.

6. Let the artist guide your eyes. You may notice that parts of the painting are hard to focus on, while other parts keep drawing your eyes in with a kind of visual magnetism. The artist has worked hard to draw your attention where he wants it, and to keep your attention from being able to linger in other places. Some sections seem brightly lit and sharply focused, while others are dark, hazy, and blurred. You may find your eyes making a circular swooping motion, or sliding off the left side of the image and having to jump back in to the middle. All of that is by design, and as you warm up to a piece, you should entrust your eyes to the visual and compositional forces which the artist has marshalled for that reason. The better the artist is, the more you can trust him to do the right thing with your eyes. Leonardo DaVinci may encourage you to let your attention roam around an evenly-lit space, but Rembrandt owns your eyeballs and puts them exactly where he wants them. You know when art teachers draw circles and lines all over a painting to show the basic compositional forces at work? This is the kind of stuff they’re trying to show (Do not actually draw lines on a painting).

These first six steps are the most important for increasing your odds of pure visual experience. But after these six steps, it is fine to move on to the next two, which re-engage your understanding at the level of representation, narration, and interpretation. Notice that the next two steps encourage you to label things, identify them, describe them, and analyze them in light of other knowledge you have. These are great things to do, but frankly they’re the two things you were most likely to do anyway. They’ll mean a lot more after the first six.

7. Say what you see. There’s a lot of weird stuff going on in some art, and when you’re confronted by a complex visual field, it’s helpful to start sorting it out and labelling the parts you recognize. Often you will hear yourself describing it and recognize that you understand more than you thought you did. The very act of labelling something can take you to the next level of appreciating it. A related tip is to act out the thing you are seeing. Put your body in the position of the body you see painted; usually you will discover that the pose is considerably more exaggerated than it seemed when you were just a spectator. Also, you will provide amusement for your fellow museum goers.

8. Use background knowledge. If you know something about the artist in question or the image you’re looking at, go ahead and bring that information to bear on it. It’s fine to say, “Michelangelo was a Platonist” as you study his work, and see if you can find connections between what you’re seeing in front of you and what you already knew. But notice that you have to keep this “what you already knew” in check long enough to have a real, new, purely visual experience of the art object. There is a great danger that we will bring our preconcieved ideas to a painting and ruin our chance to learn anything new by applying background knowledge too early and too thoroughly. Just because Van Gogh had a hard life doesn’t mean you can find a note of sadness in every picture he made. Sometimes he paints sheer joy, and you have to see that with your own eyes before you start squaring it with the other things you know about him.

I could add after this list a ninth step: Read the label on the wall. I know that you’re usually going to do that first of all, and that’s okay. But if you really want to do things the right way, follow the basic flow of analysis I’ve presented here, and you’ll proceed from fundamental visual encounter all the way up through the kind of analytic understanding the label wants to hand over to you at first encounter.