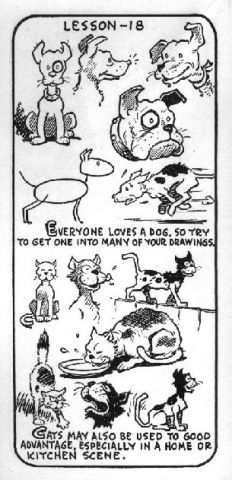

Cartooning is fun, and anybody who’d like to try their hand at it should probably go buy Scott McCloud’s excellent book on it. But if you don’t want to spend the money on McCloud’s far-reaching description of comics technique, here’s a fun free intro: Barnacle Press has a “Pocket Cartoon Course” from the 1940s available in their archive.

Cartooning is fun, and anybody who’d like to try their hand at it should probably go buy Scott McCloud’s excellent book on it. But if you don’t want to spend the money on McCloud’s far-reaching description of comics technique, here’s a fun free intro: Barnacle Press has a “Pocket Cartoon Course” from the 1940s available in their archive.

If you learn to cartoon using this Pocket Course, you have the advantage of picking up a little bit of collateral retro-jollification from it. Pretend you’re too cool for cartooning by cartooning with hipster throwbacks from a decade that never was. Put yourself in quotes and share the in joke with the in crowd. I’m not cartooning –I’m making fun of people who would cartoon! Zow!

Or just start the doodling. Cartoons offer a potent mix of word and image that people find increasingly helpful in recent decades. Even if all you can draw is stick figures, once you start to learn the basic principles of juxtaposing and sequencing you find yourself in command of vast resources for storytelling and description. The Pocket Course is full of helpful hints.

I once taught art classes in a middle school, and I used cartooning as a framework for teaching principles of design, composition, storytelling, drawing, and whatever else came up. After coaching them through the basic idea, I turned the students loose to tell any story they wanted, with mixed results –some great stuff that no adult could have generated, and some weird and scary stuff I had to report to the school chaplain. The way word and image coalesce in cartoons, it seems to me, generates some kind of direct line to the subconscious. Strange stuff comes out of your mind when you cartoon, as your verbal powers of articulation commingle with your visual powers of perception and expression. It’s as if you can say what you want to say because the pictures carry forward what the words couldn’t handle, and vice versa.

When I taught cartooning to 7th and 8th graders, it was a hands-on, highly coached environment. If you don’t have a teacher nearby, what can a book or a blog post teach you? A little. If you’ve got desire to cartoon, you’ve got all you need to make a good start. Start cranking out some cartoons and see what you can do. When you’ve got a short one that you think works pretty well, try re-drawing it and improving it. I know it seems odd to re-draw your best stuff (rather than your worst stuff), but it’s your best stuff that’s closest to the next level you want to get to.

When I taught cartooning to 7th and 8th graders, it was a hands-on, highly coached environment. If you don’t have a teacher nearby, what can a book or a blog post teach you? A little. If you’ve got desire to cartoon, you’ve got all you need to make a good start. Start cranking out some cartoons and see what you can do. When you’ve got a short one that you think works pretty well, try re-drawing it and improving it. I know it seems odd to re-draw your best stuff (rather than your worst stuff), but it’s your best stuff that’s closest to the next level you want to get to.

Can’t draw very well? There are ways to work around that. Once you’ve got something you want to say, the ability to get it said will follow. I had my 8th graders draw a five-page story about anything they wanted to, and they begged to use simple stick figures because they all felt self-conscious about their inability to draw. I allowed them to do a first draft using stick figures, and without exception they all switched over to characters who were more elaborate than simple stick figures, because they found that once they had a story or a joke to tell, they just couldn’t settle for the limited expressive range of stick figures. They wanted more complex characters to do more things with.

But start with stick figures or whatever you’re comfortable with. Get those things to do something funny or heartfelt or whatever you’re going for. The story will drive the art, and you’ll rise to the level you need to get to in order to tell the story. Most of my cartooning has used bears and sheep because they’re easy to draw. Sheep are the best: they’re wavy and bumpy even if you draw them right, so nobody can tell you drew them wrong. Plus they don’t have hands, and hands are hard.

Layout presents you with the fundamental decisions: When you’re planning a panel (the box that the art is inside of), think of it as a camera shot. How far are you from the people you’re drawing? Avoid the desire to show their whole bodies, with their feet standing on the bottom of the panel. Close up on their head, or chest and up. Is the imaginary cameraman standing beside them, in front of them, etc. Again, nobody is better at explaining this than Scott McCloud.

Layout presents you with the fundamental decisions: When you’re planning a panel (the box that the art is inside of), think of it as a camera shot. How far are you from the people you’re drawing? Avoid the desire to show their whole bodies, with their feet standing on the bottom of the panel. Close up on their head, or chest and up. Is the imaginary cameraman standing beside them, in front of them, etc. Again, nobody is better at explaining this than Scott McCloud.

Inside the panel, leave room for the words. You need to think of the words as part of the furniture that will fill up that little room of the panel. I advise you to write the words in first, then draw that little circle around them with the tail that points to the speaker’s mouth (a word balloon). If you draw the word balloon first, you’ll end up cramming the words into it awkwardly. In real life, words don’t take up space in the room, but in comics they do.

The real secret of professional cartoonists is that they make a big mess on the original page, then put a new piece of paper over the top of it, turn on a light-table underneath it, and trace the good parts onto the clean page. Another trick they use is to make their drawings with a light blue pencil, then trace the good parts with ink. When you make a photocopy of it, the blue pencil won’t show up, and it makes you look smooth and decisive. If you’re drawing on the computer, there’s a whole other way to approach this clean-up process.

Aside from the Pocket Course, there are a number of web tutorials on cartooning. Most of them are aimed at kids, but don’t let that turn you off. Go ahead and do a cartoon story for kids,and move on from there.