Here are some key passages I have long cherished from a wonderful little book, God’s Life in Us (Denville, NJ: Dimension Books, 1969), by Jean Daniélou. If “God’s Life in Us” sounds a little too devotional for you, be encouraged: the book was originally published in French under the title La Trinite et le mystere de l’existence: the Trinity and the mystery of existence. But if that sounds a little too theological or philosophical for you, just remember the English title. Whatever it takes, O readers! Because this is worth hearing.

Here are some key passages I have long cherished from a wonderful little book, God’s Life in Us (Denville, NJ: Dimension Books, 1969), by Jean Daniélou. If “God’s Life in Us” sounds a little too devotional for you, be encouraged: the book was originally published in French under the title La Trinite et le mystere de l’existence: the Trinity and the mystery of existence. But if that sounds a little too theological or philosophical for you, just remember the English title. Whatever it takes, O readers! Because this is worth hearing.

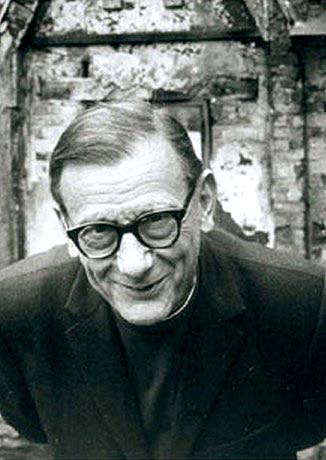

Daniélou (1905-1974) was a Jesuit theologian and patristics scholar, author of a number of important books. His work on the early Christian theology of angels is especially valuable, but perhaps books like Gospel Message and Hellenistic Culture capture his overall project best. In collaboration with Henri de Lubac he launched the indispensable Sources Chrétiennes series of patristic texts. He served as one of the expert theological advisors at Vatican II, and was made a cardinal. He rankled some senior Jesuits near the end of his life, and a shadow lingers over his late reputation. But he will inevitably make a comeback, because his published work includes many things both important and unique. There are some theological insights that are broadly distributed among the cohort of mid-century Roman Catholic theologians in the movement known as the nouvelle théologie: Daniélou especially shares affinities with De Lubac and Congar. But there is something singular in the clarity of his way of putting things.

In all his work, Daniélou expressed a uniquely powerful spiritual theology focused on the Trinity. I would not hesitate to call it a trinitarian spirituality. God’s Life in Us is the best place to catch on to what he is up to, which is why I’m providing the following excerpts with minimal comment.

Daniélou begins with some incantatory language encouraging a kind of sinking into the present reality of the Trinity:

Every baptized soul possesses in his most secret depths a sanctuary where the Trinity dwells and where, under every conceivable circumstance, he can always enter the presence of the Trinity — provided he can leave behind him the successive stages of his spirit in order to sink himself, like a stone sinking to the bottom of the sea, into the abyss which is in us and which is God’s abode. (p. 30)

He gradually adds more specificity, beginning with a theology of God the Father:

For Christian spiritual life consists in being led into the sphere of the Trinity, in becoming a son of the Father, a brother of Christ, a temple of the Spirit, in order that we may enter a personal relationship with the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. This personal life in God has a threefold aspect. First, the paternal life: as we have said, God first appeared to us as a crushing weight of holiness. There, in the revelation made to us in the Son and the Holy Spirit, God appears as Father,. As the Father — that is to say, as the original source. Essentially, He is the Principle. He is the Principle of the life of the Trinity, and it is from Him that the Son and the Holy Spirit proceed. (p. 43)

Daniélou has more to say about the Son and the Spirit, of course, but his doctrine of the Father is the place to start if you want to grasp the spirituality that flows from his trinitarianism. It begins by registering just how much God is not needy:

The life of the Trinity has no need of outside participation. This must be stressed from the start. It is perfectly self-sufficient. There is something very essential in the fact that God is total fullness of being, and therefore exhausts totally within Himself the totality of what is, so that He needs nothing else. Otherwise he would not be God. There would be an imperfection in Him. And one of the things that we must seek tranquilly to understand in God is this fullness, this total perfection and self-sufficiency. Here is something in which our spirits and our hearts can rest and take comfort, for we ourselves suffer cruelly from the limitations, failings and imperfections all around us. (pp. 51-2)

It might strike you as paradoxical that the best way to derive some spiritual benefit from the Trinity (I am using instrumental, pragmatic language on purpose here) is to acknowledge that the Trinity doesn’t need to hand out any benefits. God is, and is doing just fine. Q: What can God do for you? A: Possess fullness, total perfection, and self-sufficiency. That divine attribute of aseity, which initially has exactly nothing to do with us, is precisely the thing in which “our spirits and our hearts can rest and take comfort.”

Daniélou says more about the processions of the Son and the Holy Spirit, and then their missions. But he ponders them in relation to the divine self-sufficiency, and draws out implications for the rhythm of the spiritual life:

We might say that the movement of the Trinity is first a movement of communication in the Son and then of consummation in the Spirit. And the whole rhythm of the life of the Trinity is based on this twofold action of giving and returning. This action expresses the self-sufficiency of this life, its ability to fulfill itself without moving outside itself.

It is important for us to glimpse these things, for as our own life becomes a life of union with the Trinity and allows us to participate in the life of the Trinity, we shall encounter them again. The life of the Trinity will cast us outward toward others and at the same time gather us into ourselves within God’s self-sufficiency. It will be the opposite of anxiety and of agitation, but its action must be superabundant fullness, not self-alienation. Thus it will be a participation in God’s life, uniting this total self-sufficiency to the perfect communication that reigns in the Holy Trinity. Ultimately, everything returns to this, just as everything proceeds from it. (pp. 53-54)

God’s triune freedom is the ground of creation and of grace:

Although totally self-sufficient, the life of the Trinity nevertheless seeks to communicate itself. In other words, the Trinity seeks to share its bliss, its perfect joy with human beings. This, as revelation has shown us, was the first, the original intention in Creation. (p. 54)

Daniélou circles around this dialectic of divine self-possession and divine self-giving for some time:

Although it communicates itself to us, the Trinity never emerges from itself. It cannot emerge from itself, since all reality is consumed within it. As a result, the mission of the Holy Trinity does not represent an outward sally by God, but an ordination of all things toward Him. In fact, the life-giving action and communication of the divine life operate by attracting all things toward Him in this way, giving them life and turning them toward Him to make them live by Him. Nothing can modify in any way God’s total and perfect self-sufficiency. We must not imagine divine missions as somehow adding themselves to God from the outside –for the Trinity calls all life into being without emerging from itself.

The same applies to the contemplative soul: the Trinity communicates itself around it without emerging from its tranquility, its silence. In this sense, there is no contradiction between God’s infinite, unchangeable tranquility and his infinite capacity for love. Thus it is with the peace and silence of a perfectly tranquil soul, for it is possessed of fullness. And it is certain that we are possessed of fullness only insofar as we are possessed of God. (pp. 58-59)

He ventures one final paraphrase as a way of describing how God is not moved by lack, nor fulfilled by anything beyond the fellowship of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: everything is fulfilled first of all in God:

As we have already said in speaking of the Son, when we speak of the Holy Trinity we must always see its mission as an extension of eternal relations. All things are first accomplished in God. The Trinity is the expression of God’s life in its perfect self-sufficiency. The mission is a sort of radiation or reflection in the created world of what is first accomplished perfectly and wholly in God Himself.