No manger scene is complete without an ox and an ass in the picture. There also need to be sheep, of course, and there can be horses and cows and mice and birds and barncats and whatever else you’ve got space for. But the ox and the ass are conspicuously present. Look at a few painted examples from nearly a thousand years ago, and you can spot these two animals every time.

The Pictures

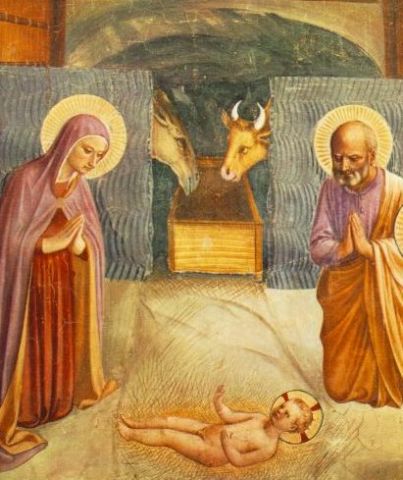

Here is part of a fresco by Fra Angelico in Florence, with the two beasts peeking in from their stalls, perhaps grateful that the baby is not yet taking up all the space in their manger:

And Giotto’s version from the Scrovegni chapel, around 1300, in which they crane their necks to see the Christ child:

Or Taddeo Gaddi’s 1325 nativity painting, in which ox and ass sit nearby with a certain dignity and nobility:

Or Duccio di Buoninsegna’s image of the Birth of Christ (1308ish), now in the National Gallery in Washigton, DC, which is about as close as the animals come to considering eating the foreign object that has intruded into their manger:

The Carols

These pictures help explain why we hear about “ox and ass” so frequently in Christmas carols. In “Good Christian Men Rejoice” we hear that “Ox and ass before him bow, and he is in the manger now; Christ is born today.” And one of the questions posed in the hymn “What Child is This,” is, “Why lies he in such mean estate, where ox and ass are feeding?” Finally, “The Little Drummer Boy” (originally entitled “Carol of the Drum”) says that “Mary nodded, the ox and ass kept time,” although the donkey is usually transformed into a lamb in most versions, to save us all from having to stop the rampant giggling that is bound to accompany the out-of-context word “ass” in modern times, especially in children’s programs. Changing the line to “the ox and lamb kept time” certainly sidesteps the anatomical misinterpretation which kids (and not just kids!) are bound to make. “Donkey” just doesn’t fit the meter of most of the traditional lines. But there is a wealth of meaning lost when the ox and the donkey are not attended to.

The Scriptures

What is that meaning? Have the songs and pictures made you curious about why these two animals go together in Christmas lore? The answer is an odd one. It involves centuries of Bible interpretation, but can be retold in a few sentences:

Isaiah 1:3 says

The ox knows its owner,

and the donkey its master’s crib,

but Israel does not know,

my people do not understand.

There we have an ox and an ass at a crib or manger. It was in the second century that the Christian teacher Origen of Alexandria (in a sermon on Luke) made the mental leap of associating this passage with the Bethlehem “crib” or “manger” (the same greek word occurs in the greek translation of the Isaiah passage as in Luke 2). Once he made that association, all kinds of meanings came rushing to the image. In the Isaiah passage, God was lamenting his people’s disobedience and contrasting it with the obedience of animals. But, Origen reasoned, when was human ignorance of God’s lordship at its most extreme? When he, the messiah, “came to his own, but his own received him not.”

Docile animals vs. rebellious people is a good image, and a good meditation for a manger scene. Add to that the fact that an ox is a ceremonially clean animal and a donkey is not, and you have a rich allegorical warrant for placing both Jew and Gentile under condemnation of rejecting Christ. Christian expositors sometimes twisted this Ox/Ass = Jew/Gentile distinction to yield a condemnation of Jews only, but with great preachers like Gregory Nazianzen, Ambrose of Milan, and Jerome handling the subject, we can usually hear a more biblical meaning of universal judgment preached from a consideration of the animals of the nativity.

One further twist: An old Latin translation of Habakkuk 3:2 says “in the midst of two animals thou shalt be known.” A better translation would probably be “in the midst of the years make it known,” but working with what they had, western church fathers added this verse to the mix and asked, “What two animals was God made known between?”

Answer? The ox and the ass.

You don’t have to think that all of this is sound interpretation to be able to appreciate the richness of meaning invested in it. The reason the ox and the ass are prominent in manger scenes is because of early Christian interpretation of Isaiah 1, and a theology of the way God in Christ overcame human rebellion through the incarnation.

We tend to hear a much squishier idea of God’s goodwill toward men at this time of year, one that ignores sin, rebellion, wrath, and a host of biblical truths that form the dark background against which Christmas joy makes sense: “In wrath remember mercy,” as Habbakuk says.

The ox and the ass stand guard at the manger as mute witnesses to the depth of human disobedience that the coming of Christ triumphs over.