If you want a theological introduction and orientation to the Quaker tradition, then Robert Barclay (1648 – 1690) is your man. Barclay (who died on this day, October 3) was born in Scotland, educated in Paris, and governed a colony in America before returning to his native Aberdeenshire. When he opted for Quakerism in 1667, he got in on the ground floor of the movement. He networked with most of the important co-founders and preachers of early Quakerism, including George Fox and William Penn.

If you want a theological introduction and orientation to the Quaker tradition, then Robert Barclay (1648 – 1690) is your man. Barclay (who died on this day, October 3) was born in Scotland, educated in Paris, and governed a colony in America before returning to his native Aberdeenshire. When he opted for Quakerism in 1667, he got in on the ground floor of the movement. He networked with most of the important co-founders and preachers of early Quakerism, including George Fox and William Penn.

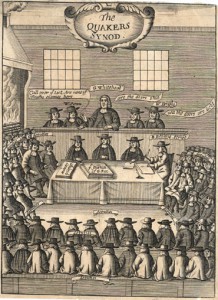

What makes Barclay the right person to read is that he attempted the impossible: to systematize Quaker theology. The first Quakers talked funny, and were hard for outsiders to understand. They didn’t even come up with a recognizable name for themselves, usually calling themselves “the religious society of friends.” People invented the derisive name “Quakers” partly so they wouldn’t have to keep saying “the religious society of friends,” or a half-dozen other non-specific ways Quakers talked about themselves. In fact, even on pain of death (and they were famously persecuted), the Quakers would continue using their strangely simple new ways of speaking. For example, one of their “Valiant Sixty,” James Nayler, was accused of claiming to be Jesus. Possibly this could have been cleared up with a few helpful explanations and distinctions. But Nayler gave answers like this when Parliament interrogated him:

Q. Art thou the only Son of God?

A. I am the Son of God, but I have many Brethren.Q. Have any called thee by the name of Jesus?

A. Not as unto the visible, but as Jesus, the Christ that is in me.Q. Dost thou own the name of the King of Israel?

A. Not as a creature, but if they give it Christ within I own it, and have a Kingdom but not of this world, my Kingdome is of another world, of which thou watst not.Q. Art thou the everlasting Son of God?

A. Where God is manifest in the flesh, there is the everlasting Son, and I do witness God in the flesh; I am the Son of God, and the Son of God is but one.Q. Art thou the Prince of peace?

A. The Prince of everlasting peace is begotten in me.Q. Art thou the everlasting Son of God, the King of righteousness?

A. I am, and the everlasting righteousness is wrought in me, if ye were acquainted with the Father, ye would also be acquainted with me.

Systematize that! Nayler was too radical even for George Fox, who would at least have told homey personal story by way of giving an account of himself. But all the Quakers tended to take a “you can kill me but you can’t make me speak clearly” approach to the religious persecution they faced.

We are in a different world, however, when we come to Barclay. Almost alone of the early Quakers, Barclay had a good enough theological education that he could explain Quaker thought in more traditional terms. His classic work is his Apology, which came out in 1676 in Latin and 1678 in English. The full title:

An Apology for the True Christian Divinity, as the Same is Held Forth, and Preached, by the People called, in Scorn, Q U A K E R S: being A Full Explanation and Vindication of their Principles and Doctrines, by many Arguments, deduced from Scripture and Right Reason, and the Testimonies of famous authors, both Ancient and Modern: With a full Answer to the strongest Objections usually made against Them.

In presenting the Quaker case, Barclay held a confident presupposition that Quakerism was just Christianity itself, purged of extrinsic additions. It was not, in other words, to be presented as a new departure, a new doctrine, or as something that just emerged in the middle of the seventeenth century. Barclay made this case explicitly, but more important was the way he took his position as somebody who had mastery of all the great voices of the Christian tradition. He supported his Quaker theology with Scripture, and also with a series of running footnotes to the great names of the Christian tradition.

Barclay’s work at least made it possible, perhaps for the first time, to have a serious intellectual engagement with Quakerism. Where before the interlocutors had to try to come to terms with ineffable experiences of a silent inner light, Barclay argued more like this (a lengthy quote to give you a sense of his voice):

Seeing “no man knoweth the Father but the Son, and he to whom the Son revealeth him”; and seeing the “revelation of the Son is in and by the Spirit” (Matt. 11:27); therefore the testimony of the Spirit is that alone by which the true knowledge of God hath been, is, and can be only revealed; who as, by the moving of his own Spirit, he disposed the chaos of this world into that wonderful order wherein it was in the beginning, and created man a living soul, to rule and govern it, so, by the revelation of the same Spirit, he hath manifested himself all along unto the sons of men, both patriarchs, prophets, and apostles; which revelations of God by the Spirit, whether by outward voices and appearances, dreams, or inward objective manifestations in the heart, were of old the formal object of their faith, and remain yet so to be, since the object of the saints’ faith is the same in all ages, though held forth under divers administrations. Moreover, these divine inward revelations, which we make absolutely necessary for the building up of true faith, neither do nor can ever contradict the outward testimony of the Scriptures, or right and sound reason. Yet from hence it will not follow, that the divine revelations are to be subjected to the test, either of the outward testimony of the Scriptures, or of the natural reason of man, as to a more noble or certain rule and touchstone; for this divine revelation and inward illumination, is that which is evident and clear of itself, forcing, by its own evidence and clearness, the well-disposed understanding to assent, irresistibly moving the same thereunto, even as the common principles of natural truths do move and incline the mind to a natural assent: as, that the whole is greater than its part, that two contradictories can neither be both true, nor both false.

This attempt to balance Scripture and immediate personal revelation is still, to Protestant lights, utterly unacceptable. But it is at least a lot closer to comprehensible, and it seeks to establish itself by appeal to Scriptural and traditional voices. That was Barclay’s gift to his own religious society of friends, and to the Christians who want to listen in and understand what the Quakers were talking about.