Remarks from a college honorary society induction ceremony, Dec. 15.

Remarks from a college honorary society induction ceremony, Dec. 15.

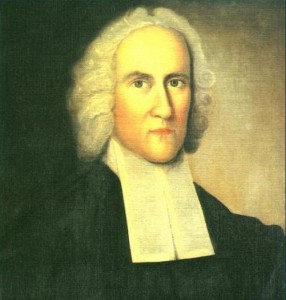

As a young man around the year 1723, America’s greatest theologian, Jonathan Edwards, wrote out a series of personal resolutions, usually published as “Resolutions of a Saintly Scholar.” These 70 numbered resolutions are soul-searching commitments to lead a life of which he would not be ashamed. #6 is, “To live with all my might, while I do live,” and #70 is “Let there be something of benevolence, in all that I speak.” Edwards stands head and shoulders above the crowd of American theologians of his generation or any other, because he was a profound thinker, a powerful preacher, a missionary, and a culture builder. He combined all these roles in one seamless ministry which baffles onlookers.

Tonight I commend to you another saintly scholar, Mark Hopson. Upon graduating from the Torrey Honors Institute last year, Mark was awarded the Angela Good Service Award, given to the student whose life is most characterized by giving, self-sacrifice, and strategic service to others. Along with this service, Mark also excelled in his academic work, as a humanities major and in his Torrey classes. He did both at once in a seamless college career that baffled onlookers.

How many students do you meet who rise to the high standard set by Jonathan Edwards? One in a thousand? One in ten thousand? One in a million? Who is a student who rises to such a level?

Mark Hopson is not that student.

I mean, let’s be realistic here. Even Jonathan Edwards wasn’t that good at this age.

But Mark is a student who I can get away with naming in the same breath as Edwards without provoking peals of laughter. And he is the student who consistently reminds me of the standard set by Jonathan Edwards, and that is high enough praise. We need more saintly scholars good enough to call the standard back to our minds. Mark is no Jonathan Edwards, but he is devout enough, brilliant enough, and effective enough in ministry that he shows us all how these things can go together seamlessly.

He is a thinker: Mark and I have had a running dialogue for a couple of years about soteriology, kicking around interpretations of Calvin and Aquinas, Paul and John. He read widely in Gregory the Great’s Moralia on the Book of Job, and in critical theory. And he is a servant: He is involved in his local church, volunteers as an usher, and also occupies that crucial position that needs a more elegant name: The “hang around and make yourself useful” guy.

But the one thing that I believe puts him over the top is his involvement in evangelistic projects in Los Angeles high schools. He was one of the founding members of the California School Project, and worked closely with the Campus Crusade staffer who got this important project going. Mark played a crucial role as an older college student who was able to coordinate the work of the adults involved with the younger college students and the high school students on the ground in the many local high schools reached by this evangelistic undertaking.

Mark leads the pack in an orientation toward putting what he learns into action. He is focused on ministry above all, and clearly came to college in order to improve his odds on being able to minister effectively. His college career is a four-year break to gather more training, resources, and maturity in order to carry on a Christian witness more effectively, to a wider audience. The key is that he does not use this ministry orientation as an excuse to skimp on his academic work, but instead uses it as it should be used: as an incentive to go as deep as possible into the subjects placed before him in course work. He is aware that college is a special opportunity to focus on subjects which he may never think so deeply or uninterruptedly about again, as the pressures of work impinge on him in the future.

Mark, thank you for reminding me of the high standard of saintly scholarship.