Does it make sense to thank someone for something they may have disowned?

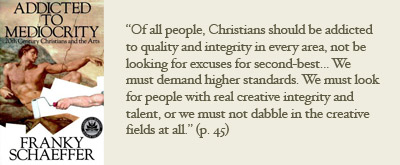

A lot has happened since Frank Schaeffer published Addicted to Mediocrity thirty years ago. He was going by the more diminutive “Franky” then, signifying, maybe, how staunchly he stood in his dad’s shadow. At the time, he thought he liked standing there; he indicates his gratitude and Francis and Edith’s prominence when he refers to them, simply, as “Dad” and “Mother” in the introduction.

The book doesn’t show up on his official website anymore, nor do any of the books he wrote for Crossway during the Evangelical stage of his life. It’s mostly limited to his fairly well-reviewed semi-autobiographic novels, his books about being a soldier’s father, his novel on the same topic, and his most recent popular books: two sometimes scathing, sometimes reverent, mostly repudiating memoirs about growing up in the Schaeffer family and then changing his mind about most of what characterized them.

All that being the case, Addicted to Mediocrity is left in a tricky little situation, still sitting on shelves, still saying its bit, but without that strong author/book continuity that makes most people so comfortable. Yet few books (if any) have had or are having the sort of impact that it has on popular Evangelical conversations about the relationship between church and the arts.

Maybe it’s because while a lot has happened for Frank since the book was published, relatively less has happened to ease many artists’ sense of unwelcome or dishonor in the Evangelical community. Franky’s polemic came from an injured artist, and its prose is stuffed just as much with indignation at injustice as it is with arguments for the arts’ high place in a Christian cosmos. That indignation, sometimes fiery hot, has consistently found an audience, and will continue to do so as long as some large group of believers senses systematic injustice toward the arts and artists in the Evangelical community.

The injustice that really gets Franky and his followers going is the insistence among some Evangelicals that the highest determiner of any artwork’s value (and, by extension, an artist’s value), is its clear communication of simple, accessible, evangelistic or pietistic ideas. Not only does this strike him as aesthetically uninformed, it strikes him as manipulative; it turns art into religious propaganda. Not only does it strike him as manipulative, it strikes him as oppressive; it renders the very personal sensitivities and concerns of creative individuals valueless. Artists are exploited on the one hand, and trivialized on the other.

This is simple: feeling exploited and trivialized hurts. Deeply. And, despite some significant movements in parts of the Evangelical community toward reconciliation with the arts, this hurt is still pervasive among serious Evangelical artists. Going further, it’s almost universal among post-Evangelical artists, whether those artists converted to a more liturgical tradition or left the Church entirely. So long as hurt like this exists in and around the Evangelical church, and until a better popular book is written on the topic, Franky Schaeffer’s Addicted to Mediocrity, with its expressive indignation, will continue to be a rallying point.

That, I think, is the main reason its influence has lasted as long as it has. Dorothy Sayers and many others have made the arguments he advances: that creativity is essentially human and significant evidence of the image of God, and that Christianity encompasses all subjects rather than being relegated to a constructed “spiritual” category. They have often made the arguments more precisely and expansively. But no one else has made them and coupled them with a comparably passionate plea. No one else has let indignation color their argumentation quite like Franky did. Franky made it personal.

Addicted to Mediocrity was Frank’s first book, and it amply evidences a writing style and social analysis that have yet to mature. His word choice can vacillate between the pedantic and the grandiose, his infatuation with commas is everywhere apparent, perpetual strings of adjectives pop up when he gets heated, and so on. Maybe I’m sensitive to these kinds of mistakes because I’m prone to them, but their presence fuels most of the negative reviews I’ve come across. And they’re right: it’s ironic for a book championing technical artistic excellence to be mediocre in its execution.

But, though I wish there was a better popular book on the topic, I’m willing, because of its influence and uniqueness, to overlook most of its flaws for now. Considered as the first book by a young visual artist who overcame severe dyslexia to write it, it’s quite good. Considered by its ability to speak into people’s self-understood situations, it’s also good. Considered as a work of written artistry, well, let’s hope for a new one to replace it. Its formal inadequacy is inexcusable given its message, but that message has proved pertinent, helpful, and powerful. For all its flaws, and despite Frank Schaeffer’s eager departure from the community to which he was speaking, Addicted to Mediocrity remains one of the simplest, most compelling expressions of the artistic crisis in Evangelicalism of the past few decades.