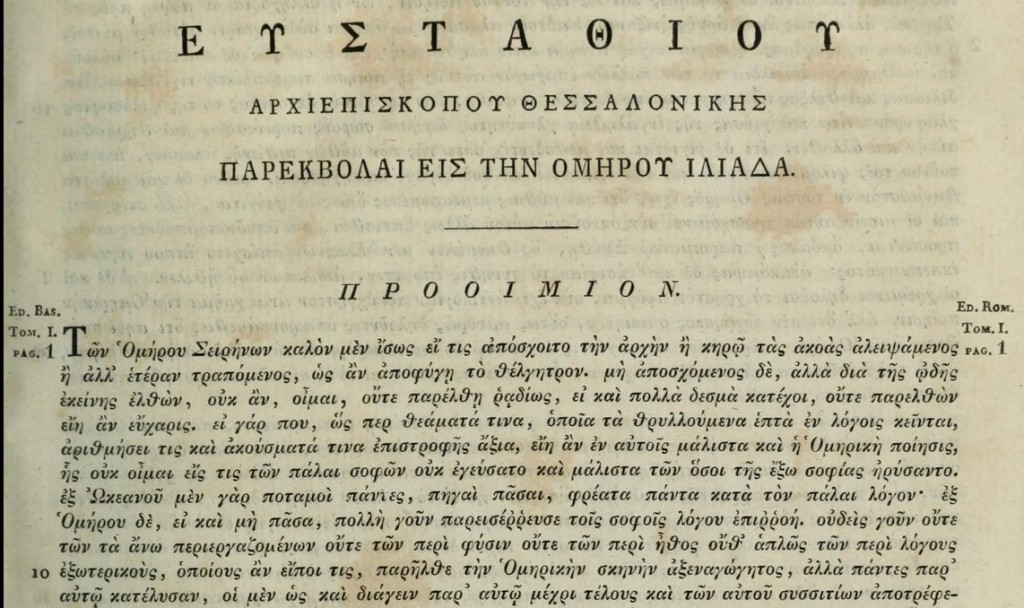

Bishop Eustathius of Thessalonica (1115-1195) wrote a long, Greek commentary on the Iliad, which he introduced with this commendation of Homer. He thinks everybody should read Homer, but his strategy seems to be making the poet seem deep, dark, and dangerous:

Bishop Eustathius of Thessalonica (1115-1195) wrote a long, Greek commentary on the Iliad, which he introduced with this commendation of Homer. He thinks everybody should read Homer, but his strategy seems to be making the poet seem deep, dark, and dangerous:

Homer is like Sirens. Perhaps it would be best if you kept clear of him from the start; if you blocked your ears with wax, or steered another course, to escape that magic. But suppose you made your way onward through the range of his song, you would not easily pass him by, even if you were loaded with chains; and if you did, you would not be glad of it.

The Seven Marvelous Sights have long been famous in story, but the Marvelous Sounds? If they were ever numbered in the same way, Homer’s poetry would be the first of them. I do not think that any of the ancient sages failed to taste of it, least of all those who drew the waters of profane philosophy.

It is an old saying that out of Ocean arise all rivers, all springs, all wells [Iliad 21.195-197] . So out of Homer flooded down to the sages most, if not all, of the great stream of language. Of all the men one could mention who labored at astronomy, or science, or ethics, or profane literature generally, not one passed by Homer’s tent without a welcome. All lodged with him, some to spend the rest of their lives being fed from his table, others to fulfill a need and to borrow something useful from him for their own argument.

Among these was the Delphic Priestess, who shaped many of the oracles by the Homeric rule. The philosophers are concerned with Homer … so are the orators; the scholars have no other way to their goal but through him. Not one of the poets who have followed Homer works outside the rules which he laid down for the craft. They imitate him, make his goods their own, do anything which will help them to be like Homer. The geographers envy him and marvel at him. The very physicians and surgeons borrow good things from him.

This poetry captivates even kings. Witness the great Alexander, who carried Homer’s book along with him even in battle, as his treasure, or as provision for his campaigns. On this book he rested his head when it was time for sleep, so that even then he should not be separated from Homer, but should dream well, even while he saw him in imagination.

And in fact Homer’s poetry is a royal thing; above all, the Iliad. The proverb may speak of “an Iliad of evils,” but this poem is really “an Iliad of every good.” Its arrangement is rather like that of drama because, although the narrative is in one verse form only, there are many characters. It is heavy with good things, which one could describe almost without end: philosophy, oratory, the fine art of generalship, teaching on the moral virtues, and in short every kind of art and science.

You can also learn innocent deceptions from this source, and how to construct advantageous falsehoods, besides stinging jests, and the rules for composing eulogies. The good sense that it will bring to any man who cares to pay attention to it is beyond description.

No one could deny to Homer’s art the qualities that are considered excellent in the art of history: rich experience, or the gifts of making stories interesting, and of educating minds, and of spurring men to nobility, or any other gift that gives fame to the historian.

You may object that his poetry is heavy with myth, and that for this reason he risks banishment from our admiration.

I answer, first: Homer’s myths are not there for fun. They are shadows, or veils, of noble thoughts. Homer invents some myths to suit his own subject matter, their allegorical sense applying to those particular passages alone. Many of his other myths had been handed down by the men of old time, but he has put them to good use in the texture of his own poetry, although their allegorical sense had no real relation to the Troy-story, but only to the original enigma in the minds of their inventors.

Second: even that did not mean that the Master of Wisdom was using myth for his pleasure. Wisdom is contemplation of truth; the wise man has the same goal; and if the wise man, then Homer too. He weaves his poetry with myths to attract the multitude. The trick is to use their surface appearance as a bait and charm for men who are frightened of the subtleties of philosophy, until he traps them in the net. Then he will give them a taste of truth’s sweetness, and set them free to go their ways as wise men, and to hunt for it in other places…

The translation, published in 1969 in the journal Arion, is by C.J. Herington, a classicist who taught ancient books as if they mattered. Herington put Eustathius’ Greek into a direct and striking English which seems almost too good to be true (able skeptics can check the Greek text, linked above, for themselves).

Why read Homer? Herington rather wickedly concludes by saying that perhaps “none of these venerable responses will be found valid. But the time has probably arrived for them to be tested afresh by a generation of readers which has been indoctrinated with” a standard set of modern reasons for reading Homer:

No General Literature course is complete without him.

He illustrates the findings of Mycenaean archaeologists.

He is made up of formulae, just like Balkan poets!

He employs an uncommon amount of fire imagery.

He contributed to the decipherment of Linear B.

Standing between the ancient/Byzantine reasons for reading Homer, and the modern University’s reasons, Herington says bluntly: “Take your choice.”