In one of the “working papers in Christian theology,” which are widely assumed to be indications of where he’s heading with a forthcoming systematic theology, John Webster argues that the doctrine of creation should occupy a more determinative place in dogmatics.

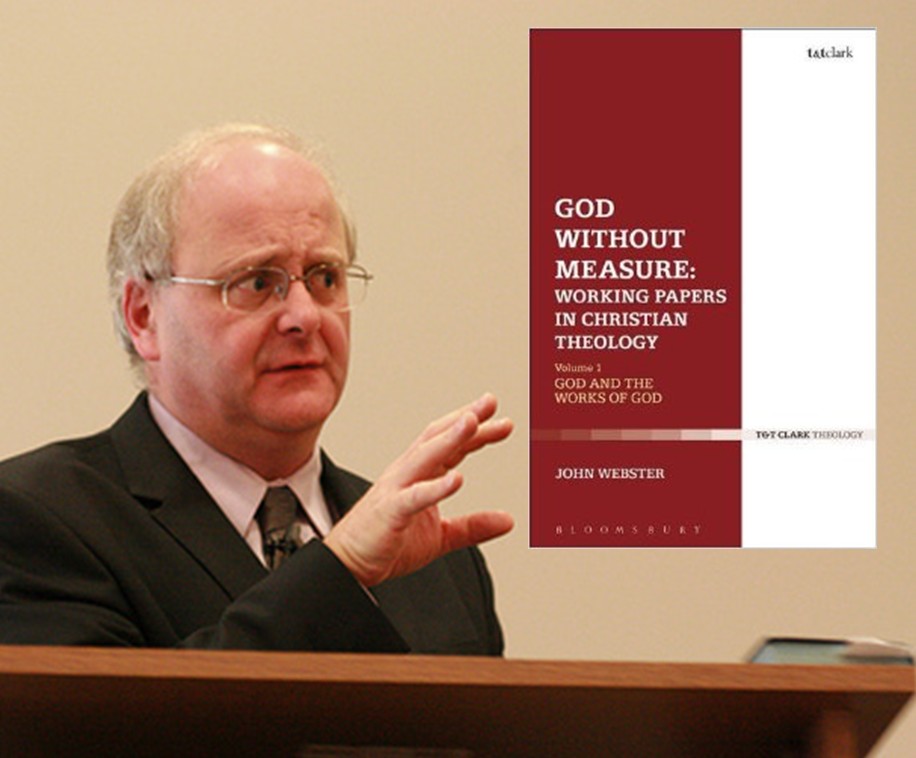

The essay is “Non ex aequo: God’s Relation to Creatures.” (already printed in a Paul Fiddes festschrift and later to be gathered in God Without Measure). There Webster calls creation “one of two distributed doctrines in the corpus of Christian dogmatics.” The first distributed doctrine is the Trinity, “of which all other articles of Christian teaching are an amplification or application, and which therefore permeates theological affirmations about every matter.” No surprise there. But Webster names creation (not salvation: we’ll come to this in a moment) as the other distributed doctrine. He admits it is less comprehensive than the doctrine of the Trinity, since creation is only a matter of God’s outward actions. But even so,

the doctrine of creation is ubiquitous…It is not restricted to one particular point in the sequence of Christian doctrine, but provides orientation and a measure of governance to all that theology has to say about all things in relation to God.

This makes immediate sense if you think of the subject matter of theology along similar lines to Thomas Aquinas: it’s about (1) God and (2) all things in relation to God. And of course Webster does think that way.

Christian teaching about creation “brackets and qualifies everything that is said about the nature and course of all that is not God.” So it’s “distributed” in the sense that it’s pervasive, but also in the sense that we’re always presupposing some account of creation even when talking about other things:

it is often implicit, built into a wide range of doctrinal material on, for example, providence, anthropology, soteriology, or the theology of the sacraments, but not necessarily breaking the surface and becoming visible. The general inconspicuousness of the doctrine after its initial explicit treatment as the first external work of God belies its systematic range and bearing.

The first thing to say when you turn from talking about God to talking about all other things is something about the Creator, about the act of creation, about createdness and creatures. Aquinas: “God’s first effect in things is existence itself, which all other effects presuppose, and on which they are founded.” Sokolowski: “Creation opens the logical and theological space for other Christian beliefs and mysteries.”

What happens when theology tries to do its work with a “misplaced, atrophied, or insufficiently operative doctrine of creation?” You might expect a theology like that to result in a low view of creation, exalting God to being everything over against a creation that was just barely not nothing. But instead, the opposite tends to happen.

Without a coherent confession of creation in place at this fundamental level, as the great second theme to function as a “distributed doctrine” governing the presuppositions of the whole system of thought, all the other stuff besides God actually grows completely out of proportion and takes over theology. “The existence and history of created things,” says Webster, “may be assumed as a given, quasi-necessary, reality, rather than a wholly surprising effect of divine goodness, astonishment at which pervades all Christian teaching.”

And here is the strangest bit, the part I was not expecting and am only slowly learning. What takes over theology in such cases is the economy of salvation. Next we start hearing that “the opus gratiae has precedence over the opus naturae, of which it is the ‘inner ground.'” As is his usual style when correcting widespread errors, Webster doesn’t name a lot of names or footnote a lot of books. But that “inner ground” business is a sideways shot at Barth’s discussion of creation –or perhaps at a one-sided appropriation of it.

It’s not just that Webster is opting for Aquinas over Barth at this point; that’s no longer surprising. It’s that in doing so, Webster out-Barths Barth by using the doctrine of creation to confess the otherness of God in a way that Barth’s mature, salvation-centered dogmatics struggled to do. Again, the problem is ceding structural priority to soteriology: “Exposition of the history of grace as the final cause of creation” results in “presenting the relation of God and creatures as one between divine and human persons and agents who, for all their differences, are strangely commensurable, engaging one another in the same space, deciding, acting, and interacting in the world as a commonly inhabited field of reality.” Why? Because of “the sheer prominence and human intensity of the central subject and episode of redemption history.” In short: too much Jesus. Or rather, a theology that is so enraptured with the story and the drama of the economy of salvation that it fails to get the necessary perspective, “the setting of the work of grace in the work of nature.”

Such an arrangement of Christian doctrine raises an expectation that what needs to be said about the natures of God and the creatures of God, and therefore of their relation, may be determined almost exhaustively by attending to the economy of salvation –the history of election and reconciliation in the missions of the Son and the Holy Spirit. Accordingly, if God and creatures are chiefly conceived as dramatis personae in an enacted sequence of lost and regained fellowship, talk of the non-reciprocity of their relation seems theologically and religiously unbecoming.

If Webster is right, that non-reciprocity (Aquinas: “The creature by its very name is referred to the creator and depends on the creator who does not depend on it”) is famously unpalatable to many modern theologians because they have let soteriology displace creation theology.

The point can be made in at least two ways; in terms of spirituality or in terms of systematic theology. Spiritually: “And so we propose to ourselves, sometimes a little guiltily, sometimes with frank confidence, that we constitute a given reality around which all else is arranged. Even God may be so placed, as God ‘for us’, a protagonist whose identity, not wholly unlike our own, is bound to us, and whose presence confirms the limitless importance of the human drama. All this must be set aside… as the mortification and renewal of our spiritual, intellectual, and moral nature proceeds.”

Systematic-theologically: The economy of salvation is not the second distributed doctrine alongside the doctrine of the Trinity. When theology turns from talking about God to talking about everything else, it must set the context with a doctrine of creation that “provides orientation and a measure of governance” to what it will go on to say about the economy of salvation.