One of the most frustrating things about being a professor in a Great Books program is that there are so many books that can, and indeed should, be in any possible curriculum, but given the constraints related to time and space that we have to deal with in the Torrey Honors Institute, some of these great classics have to be put aside in favor of other classics that do what we need them to do for any given semester. If you even whisper in faculty meetings about the possibility of adding a book, you might get a look in your colleagues’ eyes something that resembles pairs of katana swords aimed right between your eyes. So many things to consider when proposing any additions to the curriculum, like “How will it impact other readings,” or “Will it add more to our students already heavy workload of readings.” All of these are perfectly good questions that need to be addressed whenever a recommendation for an addition to the reading curriculum is made, and you know that given our human constraints, we can’t possibly cover everything, but it is still a tragedy that great classics that are worthy to be considered for the Torrey curriculum go by the way side.

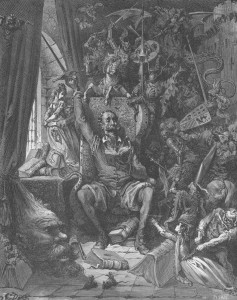

Such a book is Miguel de Cervantes y Saavedra’s Don Quixote. Cervantes’ “Sorrowful Knight” strikes us, at the outset, as a buffoon, a loveable fool easy to laugh at. After all, he neglects the care of his estate in order to pursue foolish fantasies, all culled from silly books on knight errantry. He is convinced that the world of knight errantry is the best way to live one’s life. After reading Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso and other books of knightly adventures, he decides to do something about it. He is a hidalgo, the equivalent of what might be known in England as a country squire, which means, as the second or third son of nobility, he cannot inherit his father’s title, but he can’t engage in business either, so he runs his estate, at least what’s left of it after he sells several parcels in order to buy more books on knight errantry.

He sallies forth in search of “adventures,” seeing giants and castles which turn out to be merely windmills and taverns. As his sidekick, or shall we say, his squire, we have Sancho Panza, who believes his promises of a governorship of distant islands and castles. The facts of the matter, however, are plain to Sancho, as he constantly tries to remind Don Quixote that while he sees giants, the objects he is charging towards are actually windmills. Don Quixote, undaunted, continues in his insistence that these are indeed giants, and they must be slain. When the matter is made plain to the Sorrowful Knight after a round with the windmills which throws him down on his back, he blames his delusion on “enchantment,” and continues his noble quest for adventure.

It is easy to write off Don Quixote as a deranged nutcase, but as we read through the novel, something begins to happen to us. We laugh at him at the beginning, but then we are caught up into his world, and we begin to see it from his eyes, and we end up liking it. We grieve with Sancho for the death of Don Quixote, because the vision of a world where he is more than just a worthless nar’-do-well, but an important governor and lord, will die with him. The barmaid weeps, and we weep with her, for in Don Quixote’s eyes, she is more than a mere barmaid, but a noble lady named Dulcinea. What has happened to us? How has it happened that we laugh at this bumbling fool in the beginning, but now we are caught up in his “madness”?

But this is where Cervantes has caught us in our own folly. Is it madness? In the course of the story, we begin with a self-assured notion that the world that Don Quixote imagines makes him unable to live in this world of “reality,” and our own assumptions about the nature of that reality come under question. In Part II, we are moved by sentences like these: “All I aim at is, to convince the world of its error in not reviving those happy times (of chivalry), in which the order of the knight-errant flourished…But nowadays, sloth triumphs over diligence, idleness over labour, vice over virtue, arrogance over bravery, the theory over the practice of arms, which only lived and flourished in those golden ages, and in those knights-errant.” (Don Quixote, Oxford World’s Classics, p. 528) One can hear the quintessential Christ-like question coming through in the following passage: “In the meantime, tell me, friend Sancho, what do folks say of me about this town? What opinion has the common people of me? What think the gentlemen, and what the cavaliers? What is said of my prowess, what of my exploits, and what of my courtesy? What discourse is there of the design I have engaged in, to revive and restore to the world the long-forgotten order of chivalry?” (p. 535) The answer Sancho gives is quite expected: “the common people take your worship for a downright madman…” But what can be said of his desire to “revive and restore to the world the long-forgotten order of chivalry”?

Reality is a complex phenomenon, filled with layers, not the least of which are the two layers we as Christians understand: the physical and the spiritual. We are invited by Cervantes to enter into the imaginary world of Don Quixote and reflect on these multiple dimensions. No points of views are to be ignored: not the idealism of Don Quixote, nor the realism and literalism of Sancho Panza. The point that comes across is that we must not have a reductionist attitude towards reality. While we must not fall into the Gnosticizing trap of seeing the world as only ideal without any reference to the physical and tangible universe we live in, neither should we be committed to a crass literalism devoid of all imagination and poetry. We must have poetry in our souls, which ennobles the crass and insignificant. Something in us yearns for the ideal world that Don Quixote envisions and wants to bring to our world, and yet his failed efforts should give us pause, because however ideal and good his vision, it cannot be established in this world without any reference to the needs of the here and now.

Christians have much to learn from Cervantes’ masterpiece, especially as it challenges us to look at the multiple layers of reality, and cautions us against living in just one of them. It cautions the crass literalist and materialist against a world devoid of enchantment and the world to come, as it challenges the one who gazes towards heaven to remember that the world to come is “not yet.”

We laugh at the beginning at Don Quixote’s foibles, but in the end, the Sorrowful Knight has the last laugh.