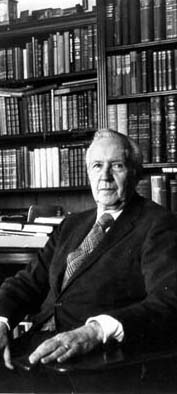

National treasure Jacques Barzun with some good advice on “What Makes Writing Right.”

Most people who coach you on writing better say things like “it’s not enough to express yourself; you have to think about your reader and strive to communicate.” Certainly there’s truth in that, and there’s even a kind of ethical demand on a writer to do unto the reader as you would have the reader do unto you. This is why it’s so important to re-write for the sake of clarity. When you come back to your own written words, you see how many things you left unclear to anybody who’s external to your own mind.

But Barzun, in the essay “What Makes Writing Right,” published in his book A Word or Two Before You Go, actually recommends a certain kind of expression over communication. The problem with striving for communication, he says, is that you’re never doing any better than taking a wild guess at what other people’s minds are going to be doing when they read your words. Imagining their mental processes is quite a feat, maybe a harder feat than writing itself. Consciously seeking communication makes your success as a composer of sentences dependent on your success as a mind-reader. “Writers muddle their meaning because they are unable to see and hear their words as these will look and sound to the receiving mind; they have not learned to impersonate the reader.” This is where Barzun recommends another approach to the task.

After you’ve written a draft, you need to step back and think critically about your work. “What is needed is a form of deliberate self-consciousness, detaching oneself from what one has put down on paper and comparing it –with what?” Not the mind of the reader, but with what you were trying to describe in the first place:

If one can’t imagine the reader and his stubborn little mind, what else is there? After scanning the state of professional writing for half a century I have come to think that for many writers there may be a better target than “effective communication,” with its implied guessing at the mind of another. A preferable aim, I suggest, is “fit expression,” by which I mean something like the work of the artist working from a model. Let the writer ask himself: is this really what I did, what I saw, what I found, what I conclude? If his word portrait is a good likeness, he will automatically communicate. And this indirect way to his goal –copying the model– has a great advantage: it gives him two known objects to match as closely as possible: the reality he remembers and the words he is setting down or scratching out.

This is a great description of how good writing can happen: say what you see, and revise for clarity by comparing the object of your description to the words you used for it. Is it a good likeness, or a distortion? Comparing two known quantities (the model and the copy) is more concrete than comparing a known quantity to an imaginary one (the words you’ve written, and the mysterious mind of your imagined audience).

Barzun also suggests that this attention to description will automatically cause your writing to find the right level of complexity for the audience. If you are describing a phenomenon that is subtle and only apparent to experts, your accurate description of it will be correspondingly subtle and only apparent to experts. If, on the other hand, the phenomenon you are describing is common to a wider audience with less specific training, the accurate description will yield a correspondingly accessible essay.

You’ll still have to think things through from your reader’s point of view. There’s no getting around that. But Barzun’s recommendation of an indirect route to that goal is very helpful.