I’ll admit it. I’m skeptical about attempts to prove the existence of God or, indeed, any of the major tenets of the Christian faith. Reinhold Niebuhr once quipped that ‘the doctrine of original sin is the only empirically verifiable doctrine of the Christian faith.’ I’m not sure I’d even go that far. There’s a lot of evidence out there that demands a verdict, but I doubt whether the verdict delivered can amount to more than an affirmation of the strong plausibility of the Christian faith.

That’s not because I question Christianity’s truth; I don’t at all. Nor do I find it particularly problematic that even the best proofs fall short of establishing God’s existence beyond the pale of suspicion. It is the Spirit’s work to draw people to Christ and convince them of the gospel truth. That he does so in part through articulating the plausibility of the gospel should be non-controversial; that we could establish proofs so certain that the Spirit’s convicting office would be redundant is inadmissible.

That caveat in place, we can enlist any number of ‘proofs’ in seeking to persuade the world of the truth of Christ and to bolster the church in its faith in Christ. Enough apologetics books have been written in the last few decades to distract us from the riches of a much longer—and rather diverse—apologetic tradition.

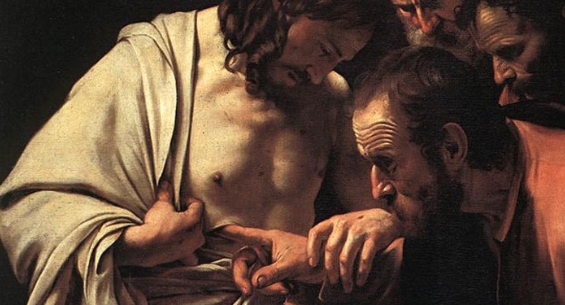

Consider one argument Athanasius of Alexandria (ca. 296 – 373) offers for the resurrection. A ‘proof of experience’, he points to virgins and martyrs, arguing that their very existence demonstrates the resurrection. Unless Jesus has risen from the dead, asceticism makes no sense; unless death has been defeated, the bold joy of the martyrs makes no sense. Here is Athanasius, in On the Incarnation of the Word:

Equally clear is it, since this utter scorning and trampling down of death has ensued upon the Savior’s manifestation in the body and his death on the cross, that it is he himself who brought death to nought and daily raises monuments to His victory in his own disciples. How can you think otherwise, when you see men naturally weak hastening to death, unafraid at the prospect of corruption, fearless of the descent into Hades, even indeed with eager soul provoking it, not shrinking from tortures, but preferring thus to rush on death for Christ’s sake, rather than to remain in this present life? If you see with your own eyes men and women and children, even, thus welcoming death for the sake of Christ’s religion, how can you be so utterly silly and incredulous and maimed in your mind as not to realize that Christ, to whom these all bear witness, himself gives the victory to each, making death completely powerless for those who hold his faith and bear the sign of the cross?

Martyrdom could not be any further from Stoic retreat from the world. The Christian martyr does not rejoice that she will be liberated from the prison of materiality. She rejoices that death will be followed by life, that death as we know it—that final menace, that abyss, that snuffing out of the light—is no more, having been ‘swallowed up in victory’ (1 Cor. 15:54).

Death for the martyr is now not the end of the line but transition, perhaps (if you’ll indulge me the metaphor) a place where we change trains and journey on. John Donne got it right:

One short sleep past, we wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

In his marvelous book on Athanasius, Peter Leithart describes the outcome of the impassible Son of God making us impassible:

This does not mean that deified humans lack feeling. It means that they are not subjected to and enslaved by their feelings. They are determined by their soul’s fixed orientation to the unchangeable God, which directs the bodily actions toward God…. What does an impassible human look like? For Athanasius, he or she looks like a martyr.

In the ‘school of Christ’, according to Athanasius, we are ‘rid…of [our] natural passions’. Because of what God does to us in Christ, death can do nothing to us. As we ‘suffer’ God’s transformative work and put on immortality with Christ, we are no longer able to suffer at the hands of the world. We may suffer—we may even die—but it will be as those who cannot suffer, as those who give their lives, not those whose lives are taken from them. This is the genius of martyrdom, in which the martyr is eminently free even as she is put to death. One word denouncing Christ would stay the hand of death, even as one word calling on legions of angels would have delivered Christ. But like her Lord, she gives herself in majestic, holy freedom, an act of pure worship. She says, with him, ‘I lay down my life that I may take it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord.’ (John 10:17-18)

Does this prove the resurrection beyond a shadow of a doubt? Probably not. But it sure is a remarkable piece of evidence demanding a verdict.