Here is a piece I wrote for a new journal called Atelier. It’s a review of the major icon show that was at the Getty Center this past year. The exhibit is long gone, but this review may help you get a sense of how great it was.

Here is a piece I wrote for a new journal called Atelier. It’s a review of the major icon show that was at the Getty Center this past year. The exhibit is long gone, but this review may help you get a sense of how great it was.

Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from the Sinai at the Getty Center

Just north of the Red Sea, nestled in between the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Aqaba, at the foot of Mount Sinai, stands the Monastery of Saint Catherine. There is nothing else quite like it in the whole world of Christian antiquities: It has been a monastery since at least the sixth century, and it was some kind of pilgrimage site for centuries before that. According to the monks on site, the burning bush itself is still growing there, and they will show it to you. They also claim to have the remains of Catherine of Alexandria transported to a nearby mountaintop by angels, and a letter signed by Muhammad guaranteeing protection for the monastery.

But let’s say you’re not inclined to believe those are the bones of Catherine, or that the signature is Muhammad’s, or that the bush growing there at the foot of Sinai is really the one Moses saw aflame. I’m cautious about such things —I once paid two hundred lira to see the body of Athanasius in Venice, and I’m still not sure it was worth it. Think as critically as you want to, but you still have to admit that the Monastery of St. Catherine has somehow preserved things preserved nowhere else. Waves of iconoclasm washed away other ancient Christian images, but they didn’t reach Sinai. Partly because the monks have revered the items and taken such care of them, and partly because the extreme isolation of this wilderness location has kept away armies in the old days and tourists in modern times, St. Catherine’s holds one-of-a-kind historical treasures.

For example, in 1859 Count Constantin von Tischendorf (yes, Bible scholars used to have names like that!) bought a manuscript there that is widely recognized as one of the most important documents in the whole field of New Testament textual criticism. Only in the late 1950s were art historians and archaeologists given permission to see and catalog the thousands of illuminated manuscripts and icons in the monastery’s possession. Since then, every book on early Christian art has to begin with a few images from the Sinai collection.

Now, just a few decades later, forty of the icons from that collection have not only been made visible to the world at large, but they have gone on tour. Some of the most important instances of early Christian art were on display in Los Angeles’ Getty Center from November 2006 to March 2007. This exhibit, entitled Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai, was an unprecedented opportunity to see these images in person. In my case, I have been studying some of these very images for fifteen years in art history and iconography books, but published photographs could not compare to the impression made by the objects themselves. When I walked into the first room of the Getty exhibit and saw the sixth-century encaustic portrait of St. Peter, his face was so familiar that I nearly greeted him by name.

The Getty curators laid out the exhibit very helpfully. The first few rooms invited the viewer to think about the nature of icons. The first room featured modest-sized portrait icons, especially images of Mary and the thirteenth-century Saint Theodosia image which the Getty used to advertise the show. The St. Peter icon all but blocked the entryway, forcing visitors to veer to the left or right as they entered. Off to the left was a small panel painting of the crucifixion of Christ, with a striking black background. This crucifixion was a comparatively rare depiction of Christ on the cross in a purple robe. While not historically accurate, this presentation of the cross emphasizes the lordship of Christ even in his act of undergoing crucifixion. One side of the wooden panel is badly damaged, sheared away but stapled back together with part of the thief on the cross missing forever. Positioned here in the first room, this picture of the cross was a clear reminder of how unthinkably fragile all these objects are, and how astonishing it is that they made the reverse pilgrimage from the Sinai wilderness to Southern California.

The largest room, most carefully laid out, was a minimalist reconstruction of the sanctuary space at St. Catherine’s. Within the intentionally barren and clinical space of an art museum, the curators placed a number of pillar icons and the rudiments of an iconostasis. They also put a photographic reproduction of an important image from the monastery which simply cannot travel: a curved mosaic depicting the transfiguration of Christ. It was good to have this large photo as the background for the icons in the fabricated churchly space, because without the image of the transfiguration, the icons in this collection seem like more of a grab-bag than they really are. The real name of the Monastery of St. Catherine is the Monastery of the Transfiguration, and meditation on the transfiguration is central to many of the icons collected there over the centuries.

It may not be immediately evident what the transfiguration of Christ has to do with Mount Sinai. However, if you spend some time pondering it and learning from the images, numerous connections begin to emerge. The most solid connecting link is Moses: Just as in the Old Testament he saw the burning bush at the foot of the mountain and then received God’s word in a blaze of glory that caused his face to shine, so in the New Testament he (with Elijah) saw the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ. From this iconographic clue, you can link together more of the icons. There are, for example, in other rooms a number of strange images of Mary standing in a green bush with stylized red flame creeping up her. An uninitiated viewer might mistake her for some kind of martyr being set on fire in green wood. But in the iconographic context of the transfiguration and Sinai, she is obviously the fulfillment of what Moses saw: she is a created thing which cannot of itself contain the glory of God, but just like the burning bush, God caused her to bear that glory and yet not be consumed by it. These connections between the various icons are really there. Though each icon rested on its own pedestal, there was a silent conversation going on among them and an exchange of iconographic information. The overarching photo of the transfiguration mosaic helped draw them together. It also showed how inferior photographic reproductions of these icons really are: the giant photo seemed bland, muted, and not worth looking at in comparison to the objects below it.

Not all the rooms in the exhibit were as exquisitely structured as this one. They were supposedly arranged according to the rubrics “Holy Image, Holy Space, Holy Site, Monastic Life, and Pilgrimage,” but I was unable to get a sense of how the later rooms were intended to be focused. One of the final rooms featured a number of images of St. Catherine, mostly rather late Byzantine and some of them glaringly Italian. For this show, the Getty moved in a Catherine image from its own permanent collection. These Italian paintings from right around the time of the Renaissance made for an interesting counterpoint to the Byzantine core of the show. The spell woven by the distinctively eastern iconographic conventions in the previous rooms began to dissolve as the viewer emerged into the more familiar western conventions of the first glimmerings of the Renaissance. There is of course plenty of overlap between the two styles, and a viewer whose sensibilities have been tuned by immersion in the oldest images from Sinai will be able to appreciate the similarities between eastern and western Christian visual styles. But the points of dissimilarity are probably more striking, and that made the show end on an appropriately dissonant note.

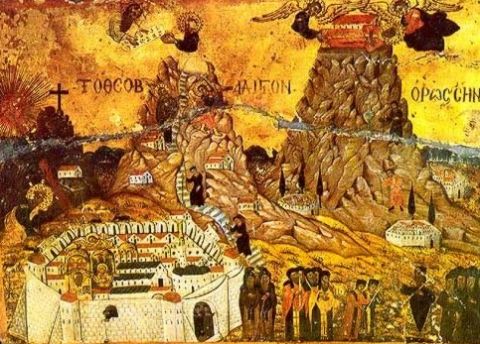

One of the last images is a quirky image by El Greco, which includes a depiction of Mount Sinai itself. But it also shows this Greek painter trying out his skills as a painter who is assertively re-tooling to paint like one of the heirs of Giotto. El Greco’s figures seem to be caught in an awkward moment of transition somewhere between the Byzantine iconic style and the western project of direct observation. It is a good reminder of just how different the pre-modern iconographic mindset is from the race for realism which came to characterize the western artistic tradition.

The sequence of rooms was laid out in a circuit, so after completing the whole loop you could just take another turn and re-immerse yourself in the older images again.