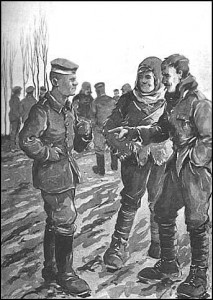

By far my favorite story about the celebration of Christmas is the Christmas truce of 1914. On the night of December 24th, entrenched and fully engaged in deadly combat, German soldiers in Ypres began to observe Christmas festivities. They lit candles, decorated a tree, and began to sing carols. After a short while, the British troops in the opposing trenches began to sing carols of their own. Singing led to laying down arms, and soon the soldiers who had been and would continue to be at war with each other were leaving their trenches, exchanging gifts, playing f ootball and even giving each other haircuts. I cannot imagine a celebration of Christmas more fitting.

ootball and even giving each other haircuts. I cannot imagine a celebration of Christmas more fitting.

That buying the best gifts and throwing the best parties is a poor way to celebrate Christmas is a truism so tedious that I hesitate to even mention it. Charles Schultz has expressed the spiritual failures of a commercial Christmas as well as anyone will need to in my generation, and perhaps in many yet to come. Yet as I watch the ways in which we try to eschew the easy trap of commercialism for better means of celebration, I wonder if even these better ends would turn out to be cheap if we could find a way into the spirit that made enemies into brothers in Belgium.

An impossibly ironic phenomenon in recent Advent seasons has been the “battle” over the public celebration of Christmas. Christmas is a thing so powerful that it stopped a world war just by existing, just by the nature of what it is. That so many have believed that one either can or ought to do battle over it seems to me to be proof that they have not seen the thing at all. The thing itself simply, easily and absolutely dispenses with battle.

I suspect that one aspect of this failure comes from our tendency to locate Christmas either in the far past, or in the distant future. When we walk through the season of advent in liturgical practice, we primarily look back on the first coming of Christ and forward to his future coming. So I wonder, when we hear words like peace and goodwill bandied about in carols and Christmas readings, whether we think either quite locally about those few people nearest to us for whom we already feel goodwill, or far into the future towards a time when at Christ’s second coming peace will come through the final elimination of all enmity.

We may expect at Christmas a saccharine and momentary oblivion to pain and suffering, but it is an unfamiliar thought that Christmas might bring meaningful peace and goodwill in the present. I think of Longfellow’s familiar lament, written as Christmas came in the midst of another war:

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said;

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the very words which haunted Longfellow are the ones that Linus speaks to Charlie Brown:

And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying, ‘Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.’

If we are to believe Linus, and I can hardly think of a more credible source, the meaning of Christmas resides somewhere in these verses. God was with us, and God will be with us again, but the work of Christmas means that even at this moment God is with us. What has Immanuel to do with us? I think the answer to this question lies in Ypres. After the truce ended, many units had to be permanently relocated. The work of Christmas had made further battle between those men impossible. As another Christmas Carol concludes, “May that be truly be said of us, and all of us.”