Now that there’s a blockbuster movie based on Tintin, the characters and situations from the classic comics will become even more famous. I don’t care very much about the movie; I only hope it (with any sequels) proves good enough to serve as an advertisement for the comic books.

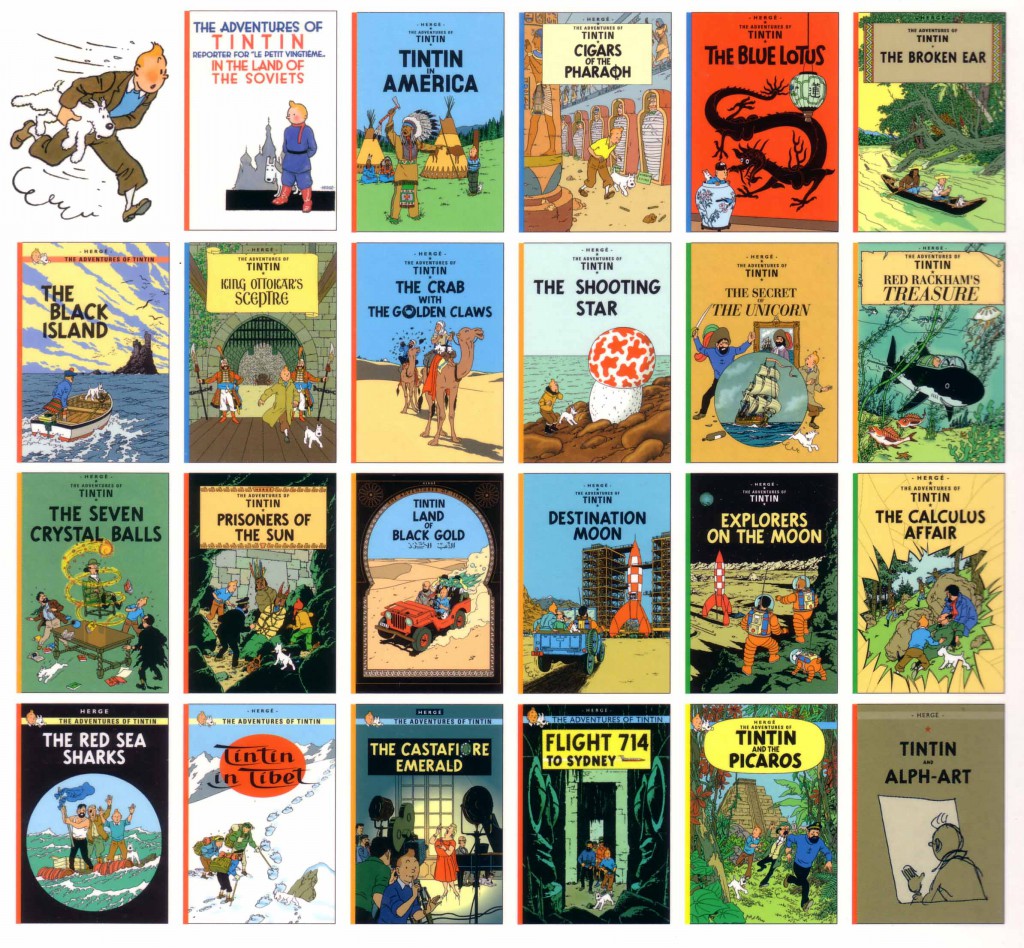

The comics are the thing. Belgian cartoonist Hergé and his studio devoted over fifty years to producing nearly two dozen full-length adventures of Tintin.

I write in praise of the comics! Find them, buy them, read them, lend them out. They are a legacy of graphic storytelling that rivals anything produced in the history of the medium.

Here are the top ten elements of the Tintin books.

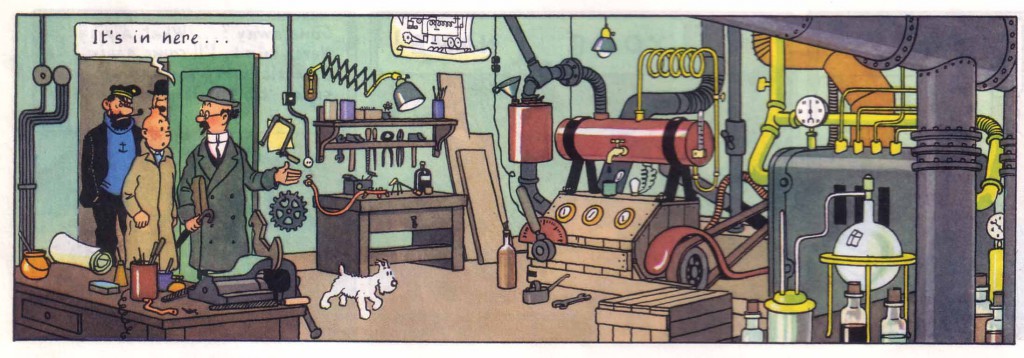

1. Detail and Clarity of the Drawings. Hergé pioneered and perfected a “clear-line” style that makes Tintin unique, instantly recognizable, and delightful to read. Any page from any book would display this strength, because it is the fundamental visual texture of Tintin. Formally speaking, the clear-line style is what makes the Tintin comics what they are. Look at this single panel from Red Rackham’s Treasure, in which Professor Calculus enters his laboratory:

Click through to the larger image for full effect. This is not the most detailed drawing conceivable, nor is it the simplest. The lines could be smaller and sharper, or more varied between thick and thin. But it combines maximum detail and maximum clarity. It is the clearest picture conceivable, for the amount of detail it has. Hergé has achieved a balance here that is unsurpassable.

What is it about an image like this (again, taken almost at random from among hundreds of pages) that makes readers catch their breath? Partly it’s the solid composition, with Snowy’s bright form thrusting out into the most open space, and the most cluttered and foregrounded objects bunching up on the right. Partly it’s the delicate coloring, with no solid black spaces but an intricate layering of shades. But mainly it’s the fact that Hergé has depicted a cluttered room without making one cluttered mark. No line here is scribbled or haphazard tossed in; each is meticulously placed.

Not only is each object depicted in perfect scale, but each object has been simplified to a certain cartoony perfection. Follow Calculus’ hand to the shelf beside the door:

The jumble of bric-a-brac is actually made up of exquisitely designed little cartoon tools. The wrench is a cartoon wrench, but not a buffoon wrench. It contains all the visual information needed to make sense, to carry out the logical function of wrenching.

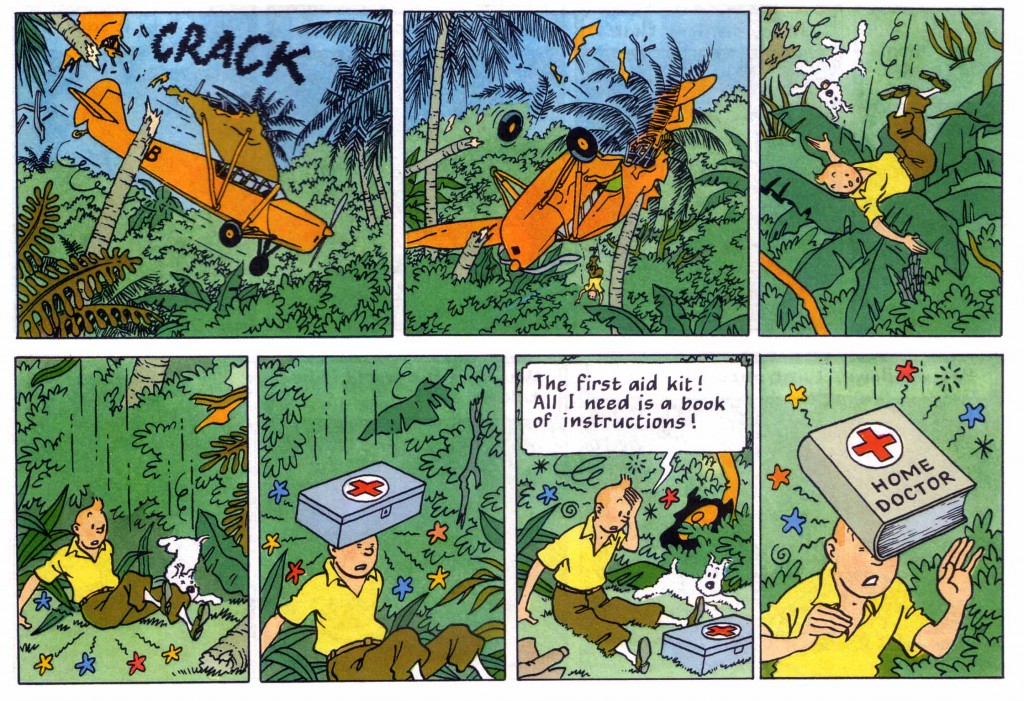

Hergé obviously cared deeply about his craft, but he also exercised great discipline in keeping the linework subservient to the story. Watch how his clear-line draftsmanship serves his narrative ends in this scene of a small plane crash from Cigars of the Pharaoh:

The forest canopy is just lush enough to show its density, but the reader can easily pick out the form of Tintin dropping out of the upside down plane. The details of the foliage drop out exactly where they need to: around the falling objects that strike Tintin’s head. Other cartoonists would achieve this effect by making the foreground objects more prominent, but Hergé keeps a steady line throughout his world. The background foliage is constructed out of lines with fairly similar thickness as the foreground items.

Every page of every Tintin book has this kind of craft and decision-making built into it. The clear-line style is the main thing going on. The Tintin movie doesn’t even try to translate that to film, by the way. It does something else altogether.

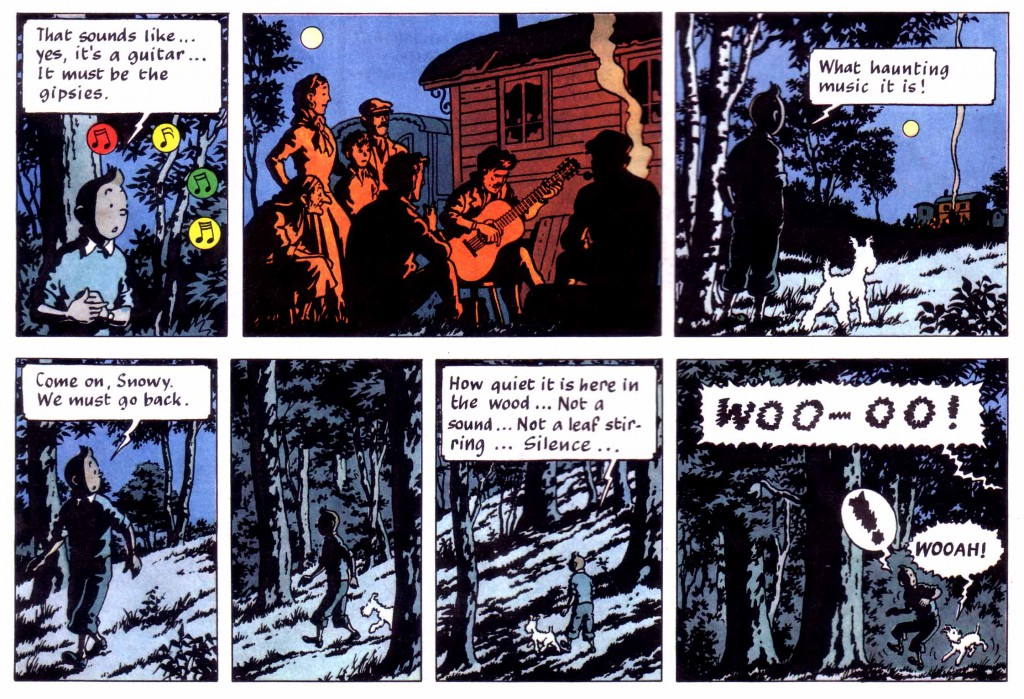

2. Atmosphere. Using a severely restrained palette of colors and lines, Hergé manages to pull off some astonishing effects. Consider this evocative scene from The Castafiore Emerald:

The colorist deserves much of the praise for the power of this scene: two or three tones of cold blue pervade the panels, barely offset by the frosty white of the conventional cartoon elements like word balloons. But around the campfire all is warm browns and oranges. When Tintin and Snowy walk away down the hillside, they are re-immersed in the steely blue night:

It’s not what you’d call subtle, but that’s the point: With such economy of means, the cartoonist achieves such powerful results.

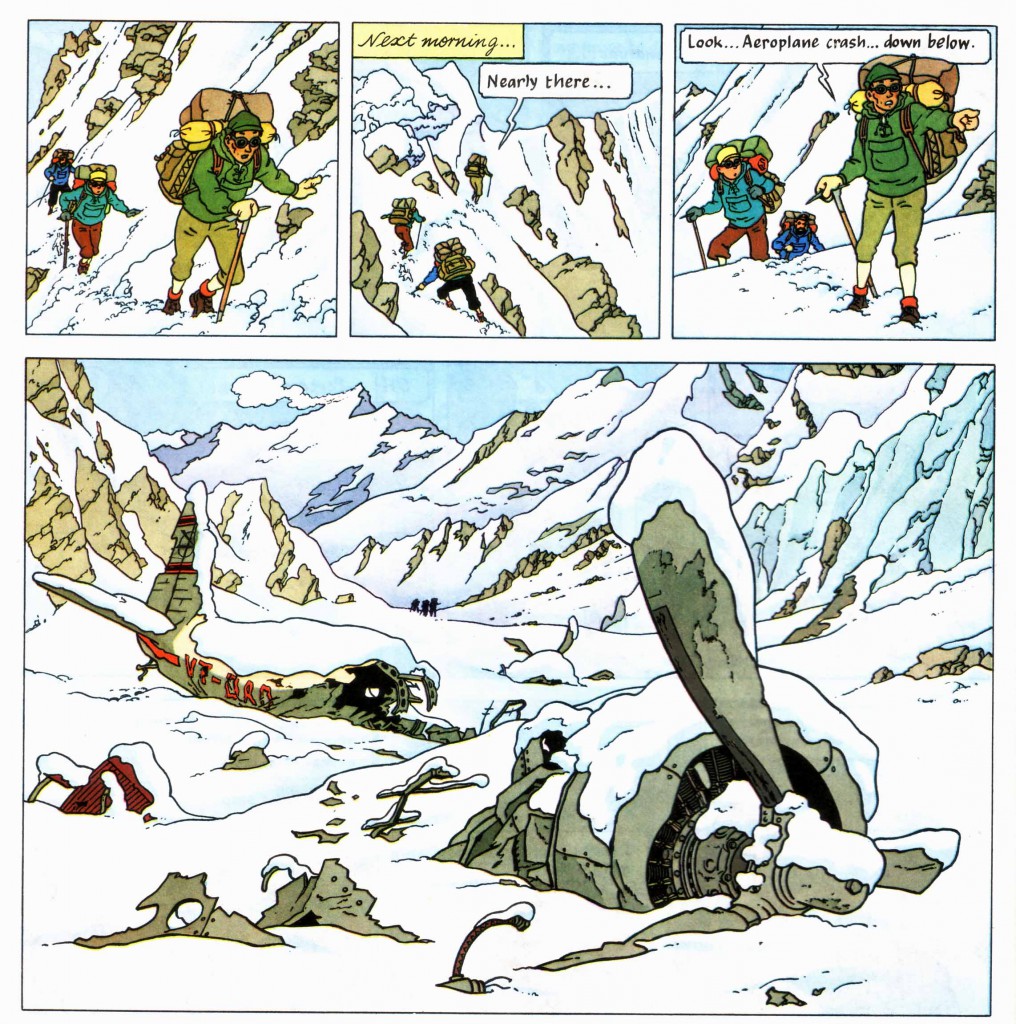

Again, Hergé isn’t just showing off, but using these techniques to support the story. In this scene from Tintin in Tibet, the atmospheric effects are crucial to establishing the feelings of elation at locating the crash site, mingled with despair of finding any survivors.

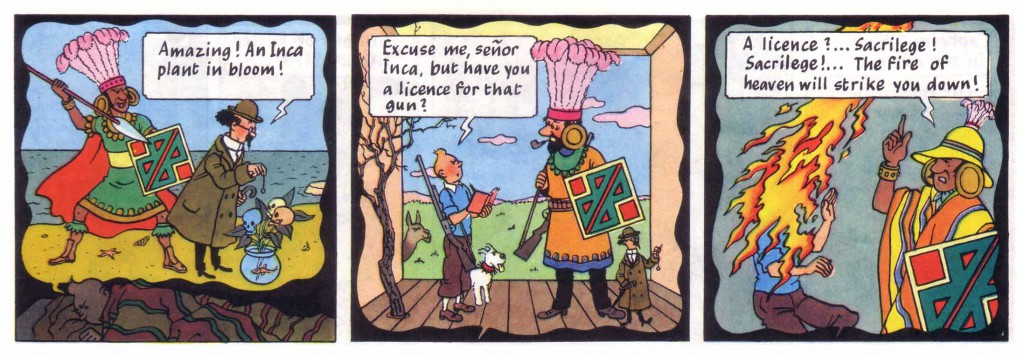

3. Cliffhangers and Punchlines. The basic unit of a comic book is the single panel, but a set of panels must be arranged on a page. Hergé originally published the early Tintin adventures serially, one page at a time. As a result, he developed the good habit of ending every page with either a cliffhanger or a punchline, depending on whether he wanted to hook the reader with suspense or satisfy them with a provisional conclusion.

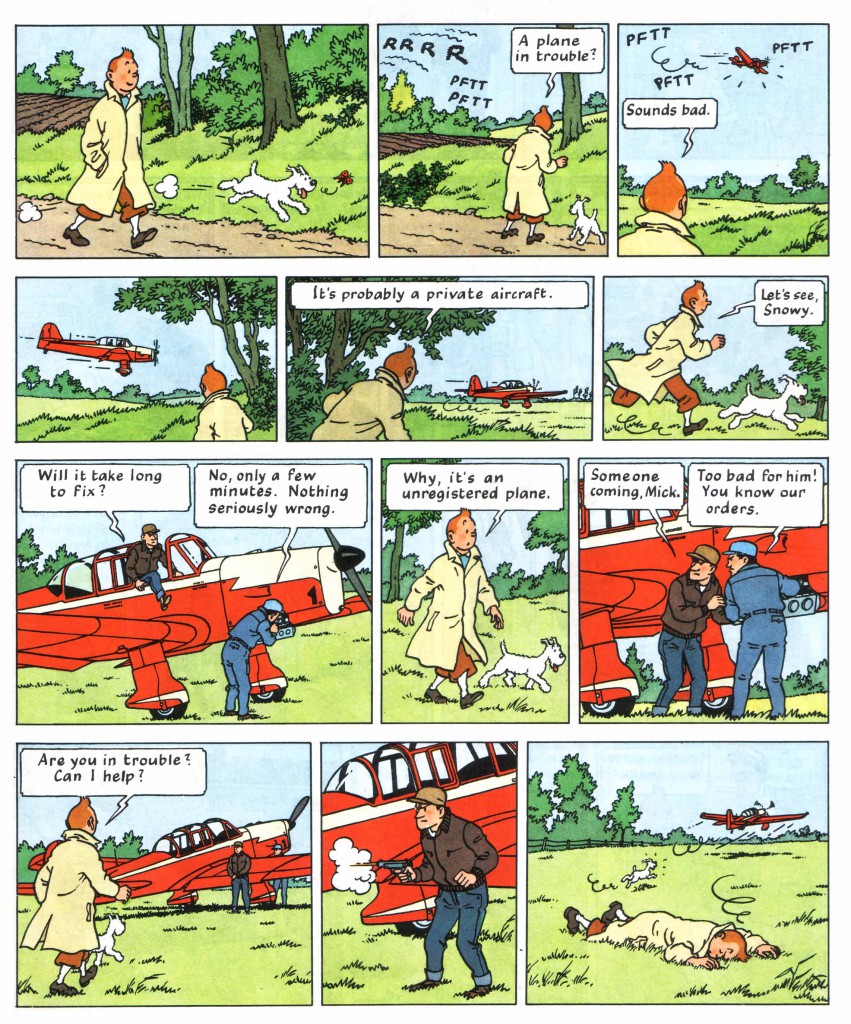

My favorite example of Hergé’s page-ending stunt is page one of The Black Island:

Is our hero dead? Who are the men in the plane? Why would they shoot him? Turn the page, dear reader! This is page one, people. The self-imposed requirement to end every page with a cliffhanger or a punchline may seem extreme, but it is crucial to the sustained readability of Tintin.

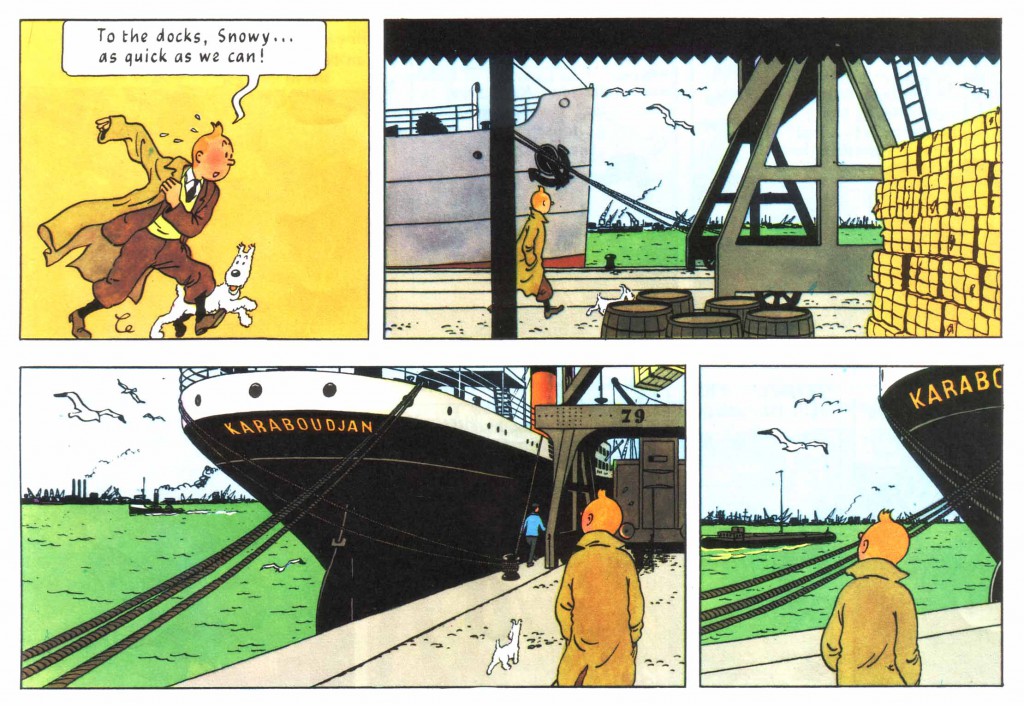

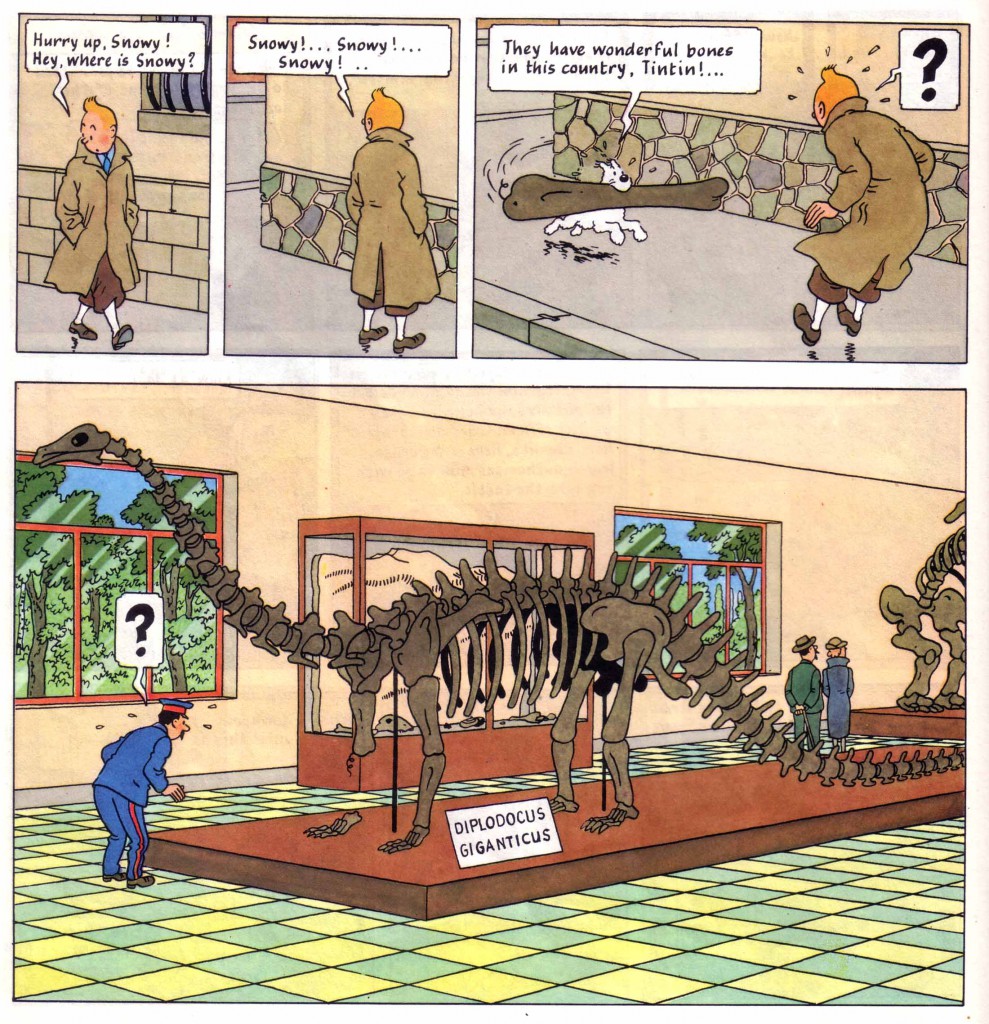

4. The Leisure of Looking Around. For all its breakneck, thrill-per-page pacing, a typical Tintin book also manages to leave time and space for exploring. Partly this is due to the fact that it’s a printed comic, an object you hold in your hand with a lot of little pictures on each page. You can look around any comic, jumping in and out of the narrative flow in a way that is unavailable in either pure text or film. But mainly it’s because Hergé built these little moments in on purpose. Consider the dock scene from Crab with the Golden Claws:

Technically, Hergé needs Tintin to be distracted so the bad guys can drop a cargo container on him from a crane. But a little distractedness could have been communicated in one panel, or two at the most. Three panels? Obviously we are expected to be looking around with Tintin, taking in the sights at the dock.

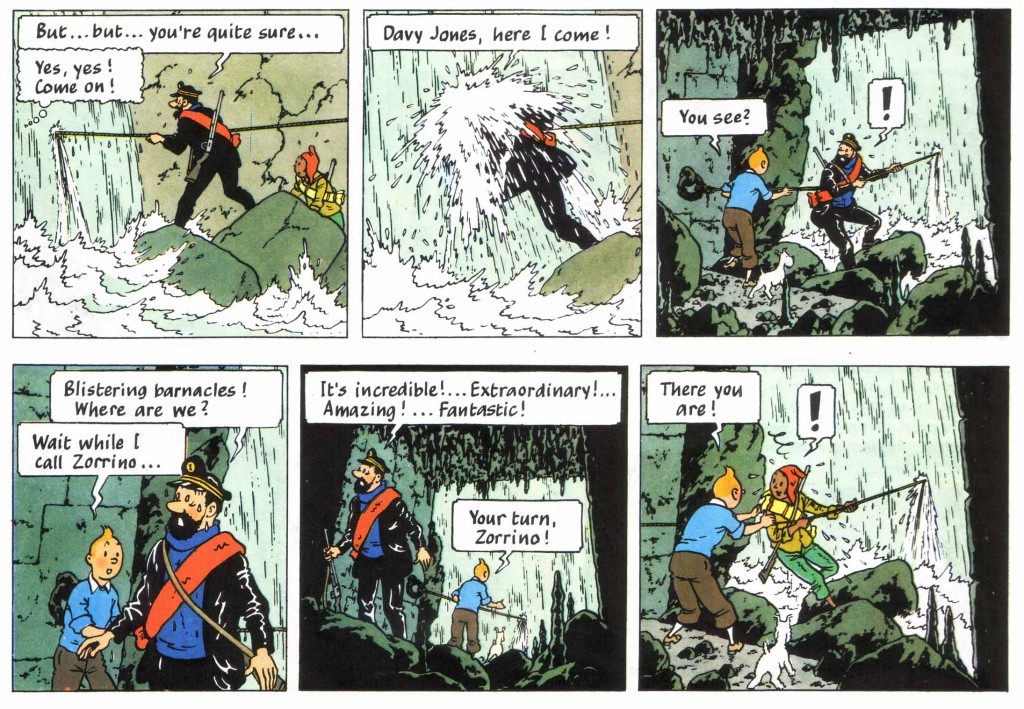

Because of the comic book medium, two things can be happening at once: the plot can be moving forward while we are taking in the scenery. To make sure we don’t miss the chance, Hergé would often have a character voice the reader’s own astonishment:

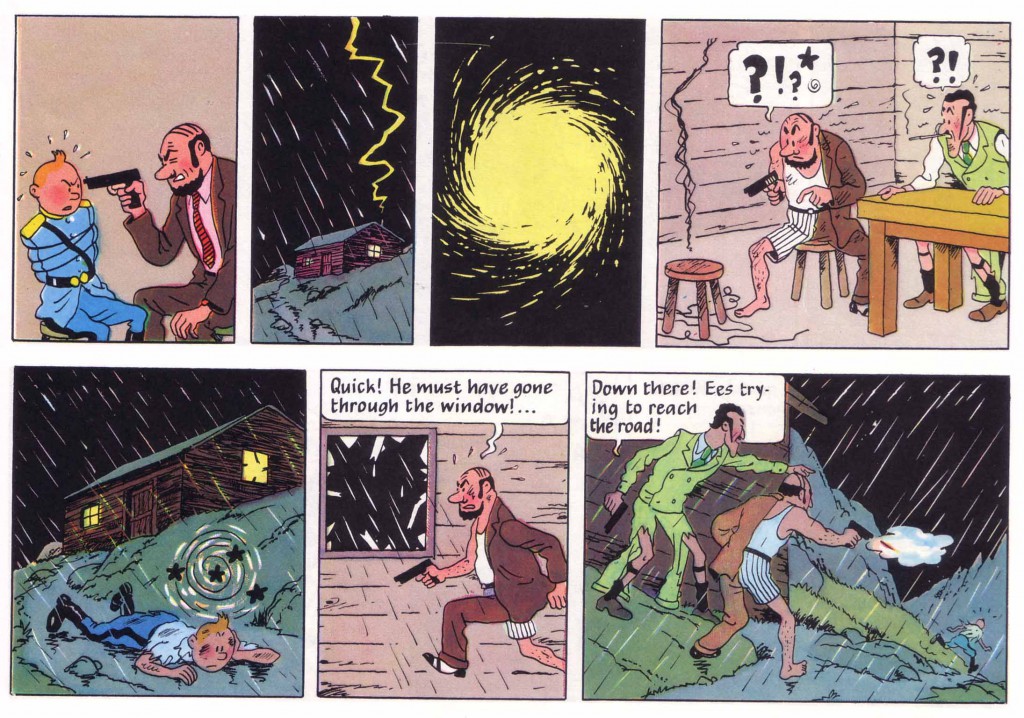

5. The Unbelievable. Some of the fun in reading a Tintin adventure is that things happen to him that could never happen. Never mind the question of how a “boy reporter” knows how to operate every kind of vehicle from planes to tanks, or how he manages to get to every hot spot for adventure time after time. The really unbelievable stuff is like this scene from The Broken Ear when he’s trapped in a cabin, tied up, and held at gunpoint. No chance of escape, right?

Unless of course a lightning ball blows him clean out of the cabin… Things like this happen pretty often to the boy reporter.

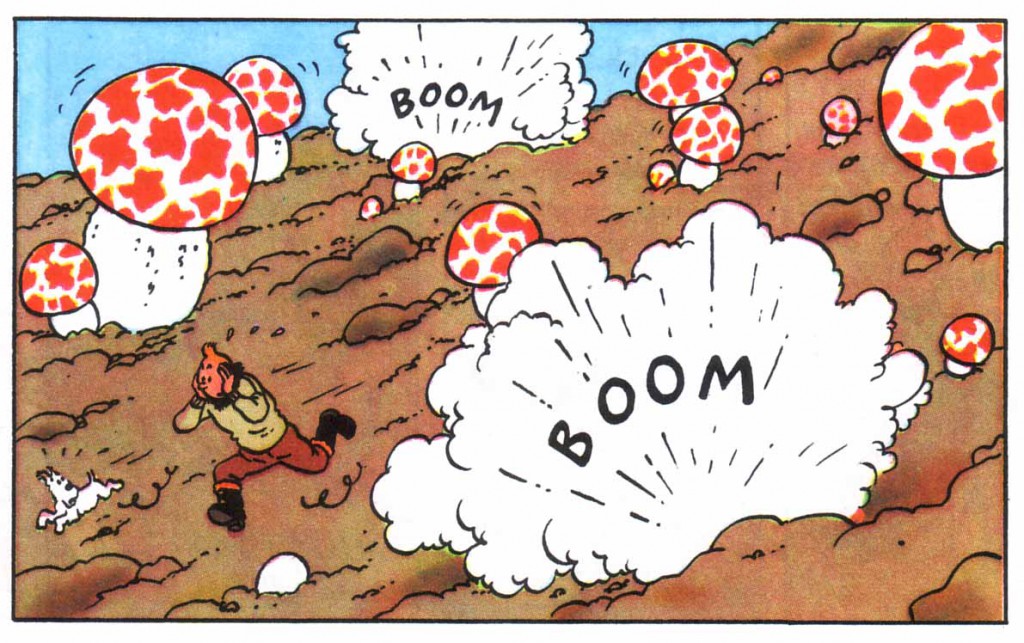

6. Spectacle and Dream. Exotic locations and amazing adventures were never enough for Hergé; he also incorporated fantasy elements into his stories. Sometimes these were fast-growing super-mushrooms, as in The Shooting Star:

But when actual plot devices failed, Hergé would have a character dream or hallucinate:

Seems like this happened in every book, allowing Hergé to mix together motifs and scenes from throughout the adventure in a kaleidescopic reconfiguration. It’s interesting that he never let it go for more than a few panels (“Pink Elephants on Parade,” anybody?).

7. Goofy Humor. From slapstick pratfall comedy to llamas spitting at Captain Haddock, Tintin’s comic relief keeps the adventures light-hearted. You can always count on Snowy to get into some dog-joke trouble, usually related to food foraging (as here in King Ottokar’s Sceptre):

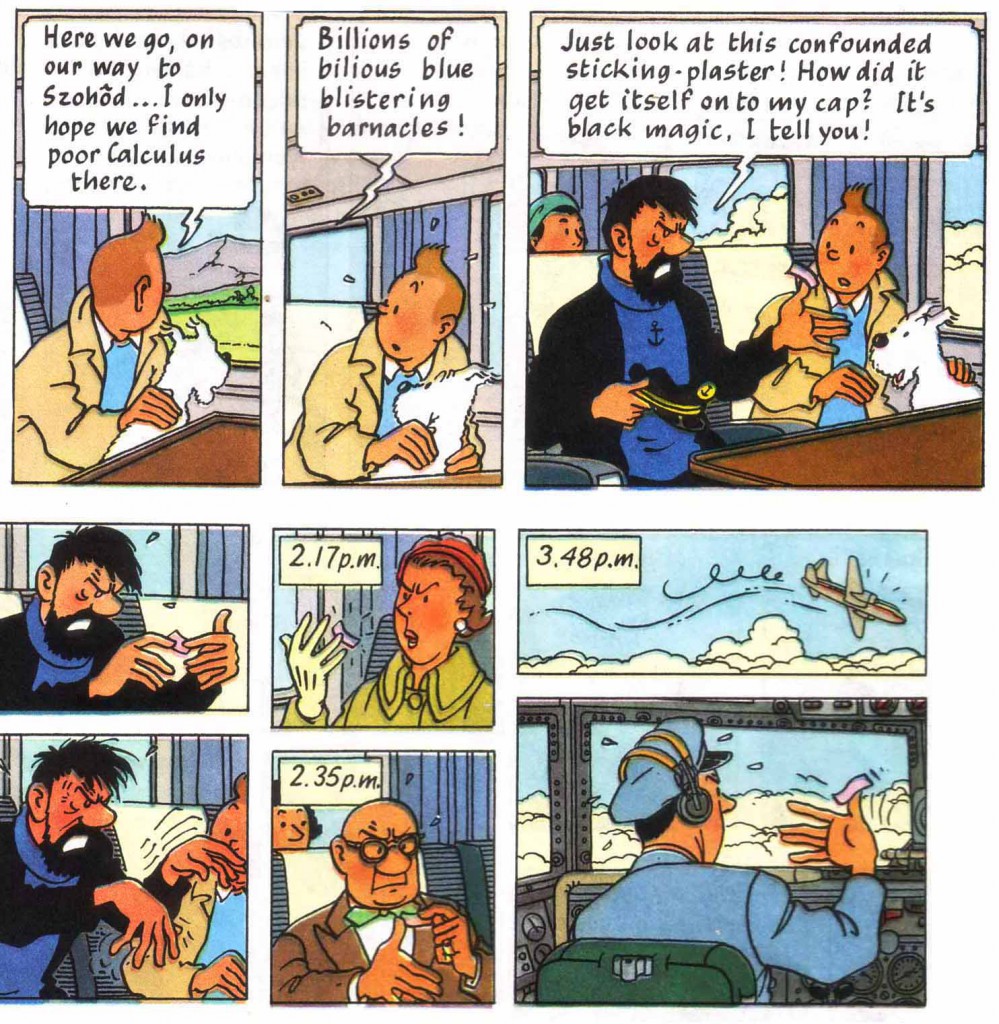

Or there’s the bit of “sticking plaster” that makes its way around the airplane in The Calculus Affair:

8. The International Angle. Up until now, Tintin has been big all around the world but small in America. At our house we have Tintin decor in many rooms: a shower curtain, handtowels, and border in the guest bath, a teapot in the kitchen, a bedspread and throw pillows. Yes, we’re into it. One of the side effects of having Tintin decor is that we flush missionary kids out of hiding immediately. They take one look at boy reporter and yell “Tonh-Tohn” or “Flupkejr” or “Tonqulskdxki” or whatever the word for Tintin is where their family was on the mission field. Since Hergé was Belgian and the strips were originally in French, and since Tintin travels all over the world, the fact that our international visitors identify him instantly adds a nice layer of the exotic.

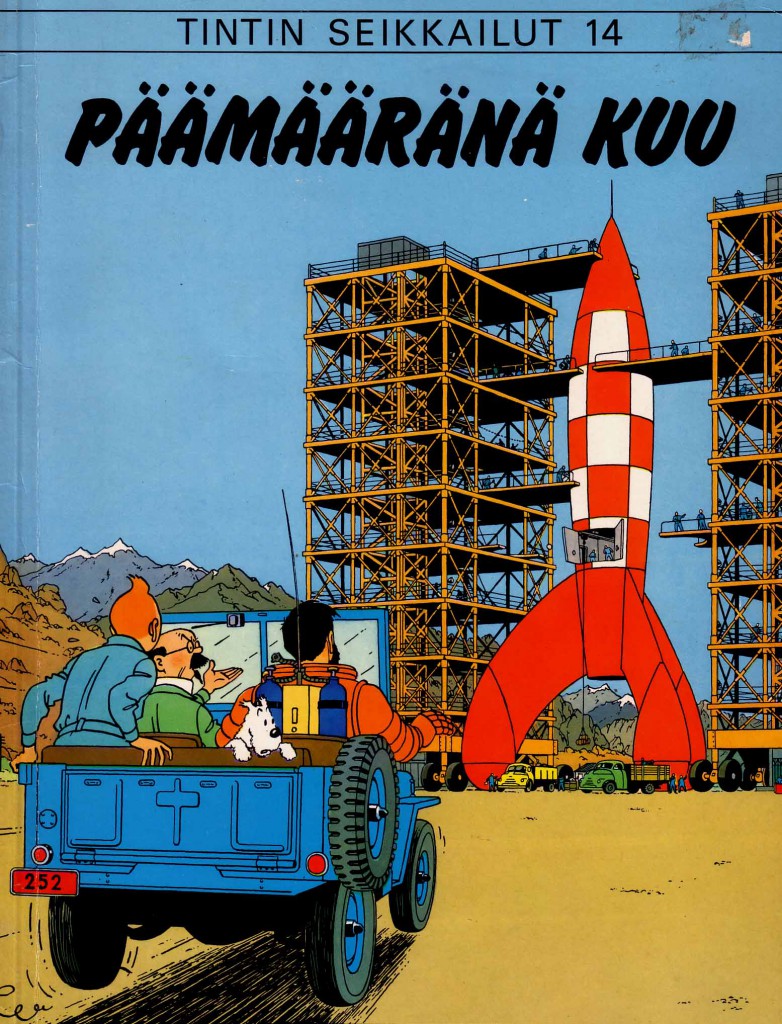

Plus I’ve picked up a few foreign Tintin books over the years, like my favorite, Destination Moon in Finnish:

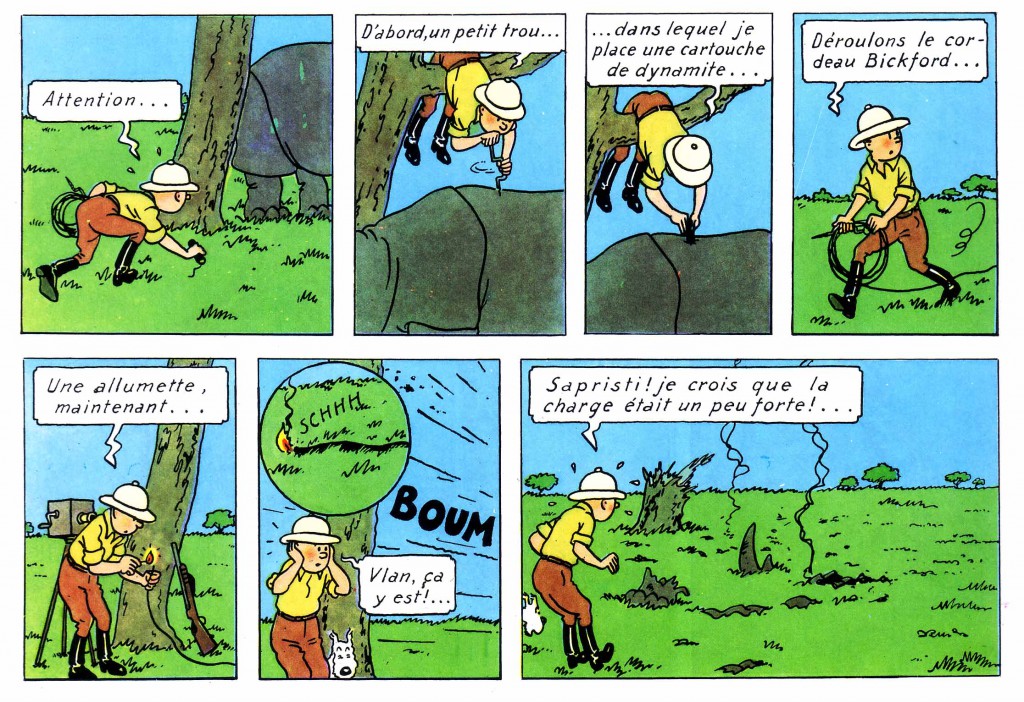

9. Period Pieces. Tintin first appeared in 1929, so it’s ooooold. To read through all the adventures is to creep through the big middle section of the twentieth century. There are some low points in there, from the bell-bottom look of the 70s in Tintin and the Picaros, to the scandalously stereotyped depictions of Africans in the sometimes-banned Tintin in the Congo. Along with its Belgian colonialism, Congo also features the weirdly light-hearted adventure of Tintin boring a hole in a rhino’s hide and the destroying it with dynamite:

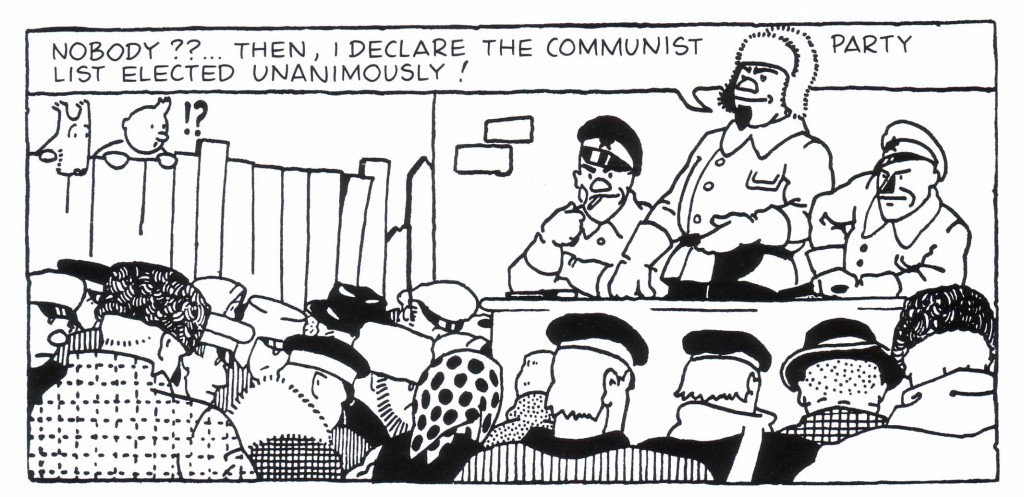

But you also get some great anti-communism in the primitive and never-colorized Tintin in the Land of the Soviets:

And either way, you are reading cartoon documents from the actual mid twentieth century, and getting to play the “so that’s what people liked way back then, huh” game.

10. Bounty! There are 23 of these books, depending on what you count as canon (Congo‘s availability and Alpha-Art‘s incompleteness being the discussion points). At about 60 pages per volume, that’s over 1300 pages of meticulously designed comic book goodness. If you don’t have a shelf full of Tintin, I don’t know how you’re planning on getting through your next big cold or flu. If you didn’t have Tintin on hand when you were a kid, it’s not too late to start making up for it. Get them, read them, enjoy the adventures of the globetrotting boy reporter.